In 2022, on our visit to the Valley of the Kings (Episode 244) we entered 3 tombs: KV62 (King Tutankhamun), KV16 (Rameses I), and KV14 (the twin tomb of Tausert and Setnakht). The descriptions of those tombs can be found in that episode; they haven’t changed.

Although Viking provided us with tickets to Tut’s tomb plus Set I plus up to 3 more of our choice, I really wanted to enter a different “extra charge” tomb, KV9 (that of Rameses VI), as well as KV7 (Rameses II).

KV9 is known for its unique ceiling – the decoration being less like what our Egyptologist guide calls “copy/paste”.

Sadly, KV7 is s not open to the public because of its damaged condition. I don’t recall that being explained to us on our last visit. Damage is not new; over millenia flash floods have eroded portions of the interior and left the tomb unstable. Instead, we toured KV17, the tomb of Seti I, which is regarded as the most spectacular tomb in the valley.

In 2022 we also had a stop at the Colossi of Memnon.

New this time were the Mortuary Temple of Hatsheput, and Howard Carter’s house.

So off we went!

At the top of the valley of the kings is a natural pyramid (above). The first pharaoh entombed here was Tutmoses I, father of Hatshepsut. It is believed that he chose this place for his tomb precisely because of that natural formation. Many Egyptologists believe that had that natural pyramid not been here, the Valley of the Kings might not exist in this location.

Our guide Walid, who already has a double Masters degree in different aspects of Egyptology, is currently working on his PhD on tomb writings. He’s the perfect guide for a visit to this valley, and made a huge difference to our understanding of what we were seeing:

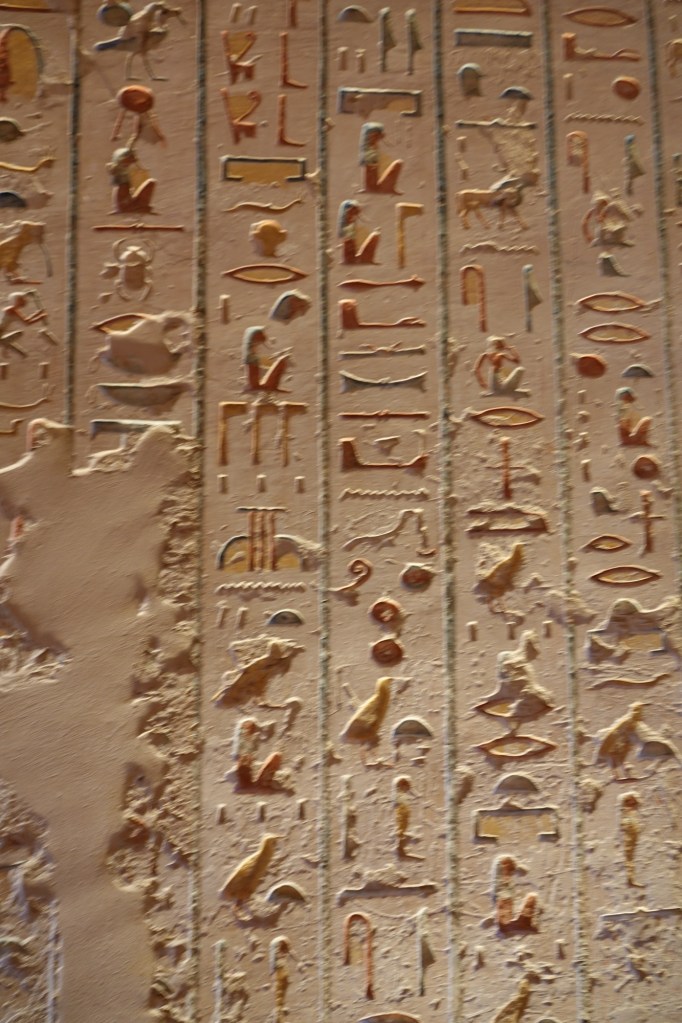

All tomb pictures, without exception, are of the journey of the pharoah to the afterlife.

The daily routine for ancient Egyptians was 12 hours waking, 12 hours sleeping. The ancients’ understanding of what the afterlife would look like was based on the sometimes fantastical visions seen in their dreams. All of their relatively brief mortal life was considered just to be preparation for an afterlife which would be eternal. Ordinary people were not mummified, but for a pharoah who “deserved”entry into heaven, construction of the tomb that would hold their remains began on the day they became pharoah.

Each tomb was divided into 12 “gates”, one for each hour of the pharaoh’s mortal life, and each representing a challenge to be overcome before reaching the afterlife.

Each of the 12 steps also provided a chance to learn one more thing about the afterlife; the drawings in the tombs depict what the pharaohs believed the afterlife would look like.

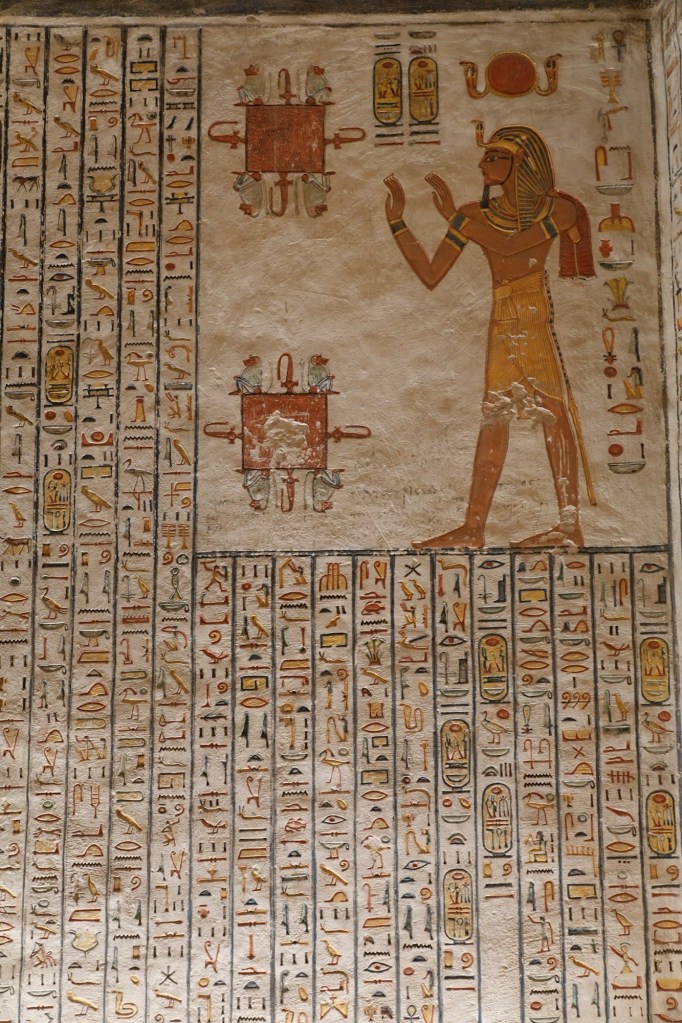

Walid explained that entry to the afterlife is analogous to entering a foreign country. A passport must be shown at the entrance.

The first picture in each tomb is of the pharaoh showing his “passport” to the god of the afterlife (passport control) . His passport is the 5 fingers of his left hand. Early fingerprint recognition!

Gate 2 always includes a hieroglyphic text which translates (in every one of the 62 tombs) to the biography of the pharoah buried there. It’s a “reference check” for entry to the afterlife. Interestingly, the biographies only include the good things!

Gate 3 represents beginning their work in the afterlife, which was described to us as “less a vacation and more a foreign job assignment”. In the afterlife, they will no longer be pharaohs, but will be required to work. To avoid this, each pharoah’s tomb had 365 statues of themselves carved and placed into niches – intended to do their work for them!

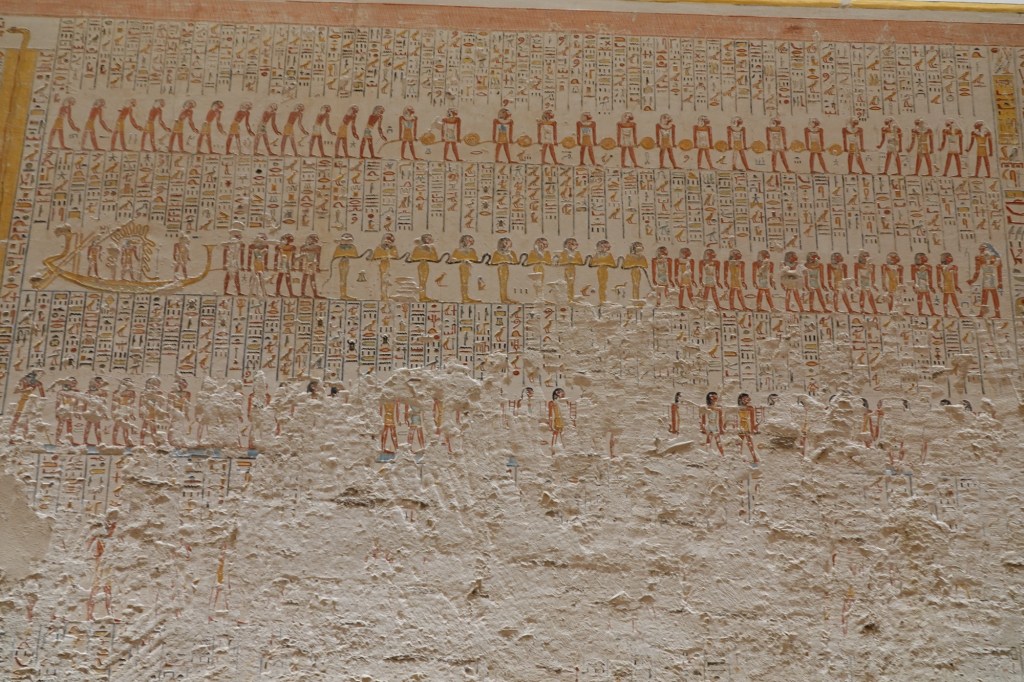

Gate 4 is all about transportation: boats to carry the pharoah and his goods from gates 4 through 12.

Every picture is a one way image facing to the burial chamber. Any figures facing the opposite direction are trying to prevent the pharaoh’s journey. The pharoah must decapitate them in order to overcome them.

Figures depicted upside down are also evil obstacles.

Finally, at Gate 12 the mummy rests in their sarcophagus.

The end wall of that final chamber looks like another gate, but is a false door, representing a new Gate 1 beginning the next 12 hours. It is carved or painted with a sun and a foetus, symbolizing rebirth.

“Gate 13/Gate 1”

Egyptologists know all of this by translating the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead , images of which we have seen inscribed inside the shrines that hold sarcophagi.

We stopped at the sign showing the layout of the valley’s largest tomb. Like the tomb of Rameses II, tomb KV5, which was a family mausoleum built to hold the mummies of all 112 of Rameses II’s sons, is too badly damaged to allow tourist access. While KV5 is the largest tomb found so far in the valley of the kings; KV 62, King Tut’s, is the smallest.

The first tomb we entered was KV2, the second tomb discovered here, which was built for Rameses IV. While it was the first discovered, it has only recently been prepared for tourists, with wide ramps and lots of railings.

Next Walid led the group to KV17, the tomb of Seti I, a space thought to be the best tomb currently open. Guides are not allowed to narrate in any of the tombs, so we had to be content using information we’d already been given.

There are 151 steps involved accessing this tomb.

While the rest of our group visited KV62 (King Tut), Ted and I descended into KV9, originally intended for Rameses V, but actually used for Rameses VI.

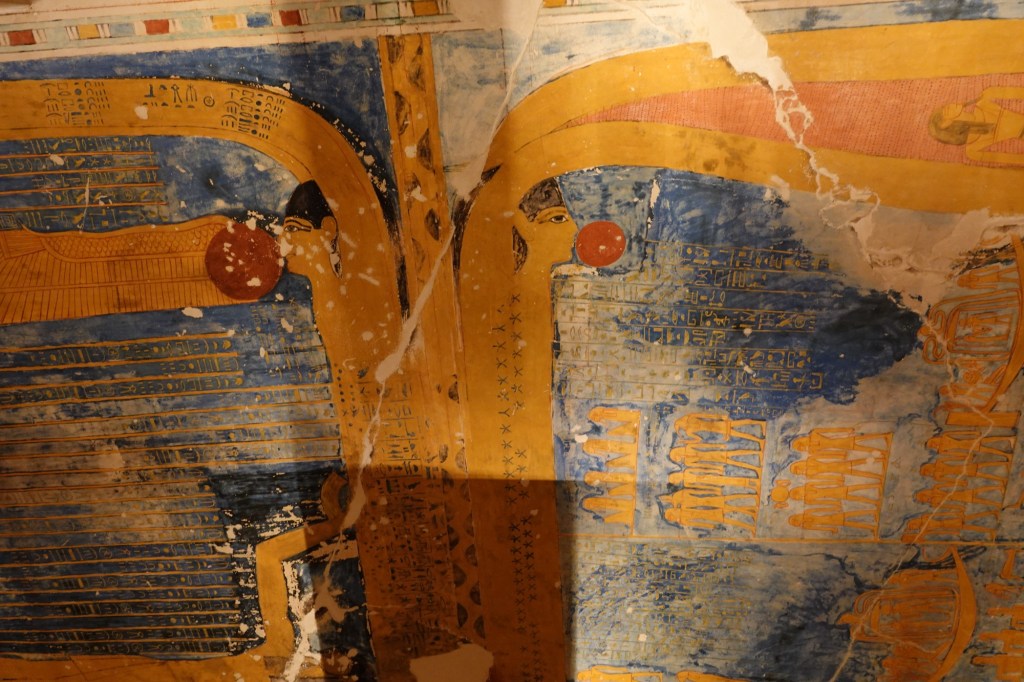

The highlight of KV9 is the spectacularly intact Nut ceiling, showing the path of the sun from her mouth (swallowed each night) …

….through her body to be rebirthed each morning. Unfortunately neither Ted nor I were able to get the entire ceiling edge-to-edge in a single photo.

The last tomb we toured was KV11, the tomb of Rameses III.

Walid had promised he would tell us about the pigments and processes used in tomb painting. The pigments of course were all natural: white limestone, red iron oxide, black carbon/charcoal, blue calcite, green malachite, yellow egg yolk. Powdered pigment was mixed with egg white and enough water to create the desired consistency and then aged underground in alabaster jars.

The stencils for the paintings were hand drawn in black ink onto the walls. Once approved by a master artist, the designs were coated with wet linen sheets through which the ink could be seen. Hand painting was done onto the linen sheets, which were then left to cure for 6 months, after which the linen was removed. Effectively it was the same process still used many hundreds of years later for painting frescoes.

Walid mentioned that while we were in KV9 we should look closely at the pharoah’s hands at Gate 1. Bizarrely, the pharoah has an extra hand, which was revealed when plaster fell from the tomb wall. It seems that there were corrections to the angle of the hand made after its original painting, and the mistake is now revealed.

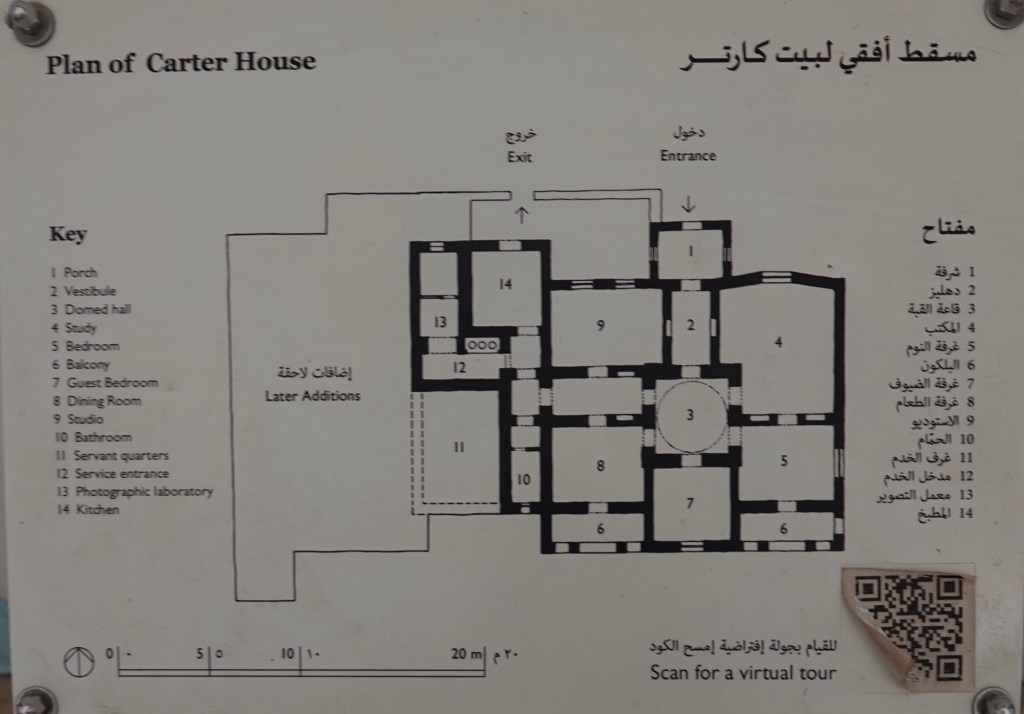

We left the tombs and had about 15 minutes to tour archeologist Howard Carter’s house, the place he lived during his excavation of King Tut’s tomb.

Despite its simplicity, it really was quite European and luxurious for a location in Egypt.

The floors are Spanish pasta tile, similar to what we saw in colonial homes in Mexico.

There is a guest bedroom that often hosted Carter‘s niece, and also the visiting Lord Carnarvon when he stayed closer to the site instead of going back into Luxor to a hotel.

Although the house has a small dining room, apparently Carter preferred to entertain his friends at the nearby hotels on the other side of the Nile.

Although there is a bathroom with a toilet, there was no piped water supply on the west bank of Luxor. Carter’s house relied on a nearby well and deliveries of Nile water for drinking and bathing.

There was a purpose-built dark room for photographer, Harry Burton, who was hired to photograph the excavation site.

Carter would have had household staff responsible for cooking using the wood-burning stove in the kitchen.

It was important to document not only work being done on the site, but also details of each of the artefacts that were found. Rather than do a series of black-and-white photographs, Carter used this studio to hand paint full colour pictures of the finds.

Not surprisingly the largest room in the house is Carter’s study, which would have been filled with tables and bookcases.

Carter’s own bedroom was strategically placed facing east to receive what was available of morning, sun and cooler breezes. It had its own screened porch.

Outside the house where there is currently a restaurant there is also a wall of posters explaining timelines and legalities involved in the excavation. It certainly seems that Lord Caernarvon would have preferred to be the exclusive owner of everything that Howard Carter found, but that eventually – and thankfully – was not to be. The artefacts from the tomb are those that we saw just a couple of days ago at the GEM.

Our next stop was at the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut , which we saw yesterday from the vantage point of our hot air balloon. Daughter of Tutmoses I, she was the first female pharoah of Egypt. Her half brother Tutmoses II would have been in line for the throne, so they married strategically and reigned together for almost 20 years. Tutmoses II married a second wife who gave him a son (Tutmoses III), who was very young when his father died. As the only male heir, he should have become pharoah. Hatshepsut, his stepmother, instead made him the head of Egypt’s army and sent him to Nubia, where – at Hatshepsut’s orders – he was imprisoned, leaving Hatshepsut as the only surviving member of the royal family.

Egypt was not ready to accept a female pharoah though, so she disguised herself as a male, wearing a false beard and men’s garb. In that disguise she ruled Egypt for 22 years.

Under her rule, the Egyptian economy was strong, and the military was powerful, although the country remained at peace. Near the end of her reign, the queen fell in love with her chief architect, Sekmuht; there is some debate among Egyptologists as to whether they married in secret or simply remained lovers. What is not under debate is the fact that this mortuary temple was built as Sekmuht’s gift to his queen.

This temple’s symmetrical, almost Georgian design is unlike any other temple that has been found in Egypt. Unfortunately, the queen died just before the temple was completed. Upon her death, it was converted to a mortuary temple, with the statues on the highest level showing the queen as a male, complete with her false beard, and of course with arms crossed and legs together, indicating that she is dead.

The queen, whom everyone became convinced was a male, was buried in the valley of the Kings. Walid pointed out a hole to the left above the temple, which leads to an extremely long tunnel. That tunnel ends at the tomb of the queen. When her tomb was discovered, all of the images of her face were defaced. That was done by her stepson upon his return to Egypt and his crowning as pharaoh Tutmoses the third. This is the same stepson who toppled one of Hatshepsut’s obelisks at Karnak temples, and removed her name from any cartouche that showed it and replaced it with his own name. Having been jailed by the queen for the 22 years of her rule, it is probably understandable that he wanted revenge.

Fun fact: the opera Aida was performed here at Hatshepsut’s temple.

There is not a lot of the wall decoration, still surviving in the temple, however, there are two notable murals. One is a mural depicting Anubis, Amun Ra and Hatshepsut, with the gods still visible, but the pharoah’s image that was in the centre completely scraped off.

The other is in a temple to Hathor, within the larger temple, and shows Hatshepsut suckling from one of Hathor’s udders. The image is difficult to see even when standing close, because it is inscribed quite shallowly. I circled the portion on the image that is shown zoomed in in the second photo.

The multiple cave holes and tomb entrances surrounding the temple belong to workers who died here during its 20 year construction. Nothing has been found in them.

The one hole that did have significance was located above and behind the temple. Exploring it led eventually to Hatshepsut’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

The Queen‘s mummy was not found in her tomb, but was later discovered under a portion of the Karnak temples. DNA analysis revealed that the queen was a large woman, probably making it easier for her to disguise herself as a man, and also revealed that she died of cancer. We will see her mummy at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in a few days.

Side note: even in the first week of December, by midday in the Valley of the Kings, it was HOT, although at 29°C/84°F it has nothing on the 42/104 we experienced during our last visit. Despite how interesting the valley was, we were all fading fast.

Our last stop of the excursion was to revisit (for us, anyway) the Colossi of Memnon.

I don’t remember on our previous trip here being told the story of why these two statues, which are both of Amenhotep I and originally flanked a huge temple gate, are called the Colossi of Memnon. The name dates to the Ptolemaic period, when the Romans were here. The Romans worshipped both the ancient Egyptian gods and their own Roman gods, one of whom was Memnon, the God of love. Memnon and his wife were believed to be the perfect couple. One morning Memnon awoke to find his wife gone; he searched the entire universe for her. When he could not find her, the result was that every morning he awoke screaming and crying. When the Romans found these two colossal statues, they had already been damaged by earthquakes and small holes in the stone screamed with the wind going through them. There was also evidence that looked like tears coming from the eyes. As a result the Romans named these the Colossi of Memnon after their own god.

Then it was back to our ship for an afternoon of sailing to Esna, a rudimentary Arabic lesson, and time to write. Staying caught up with narration and photos has been a challenge !

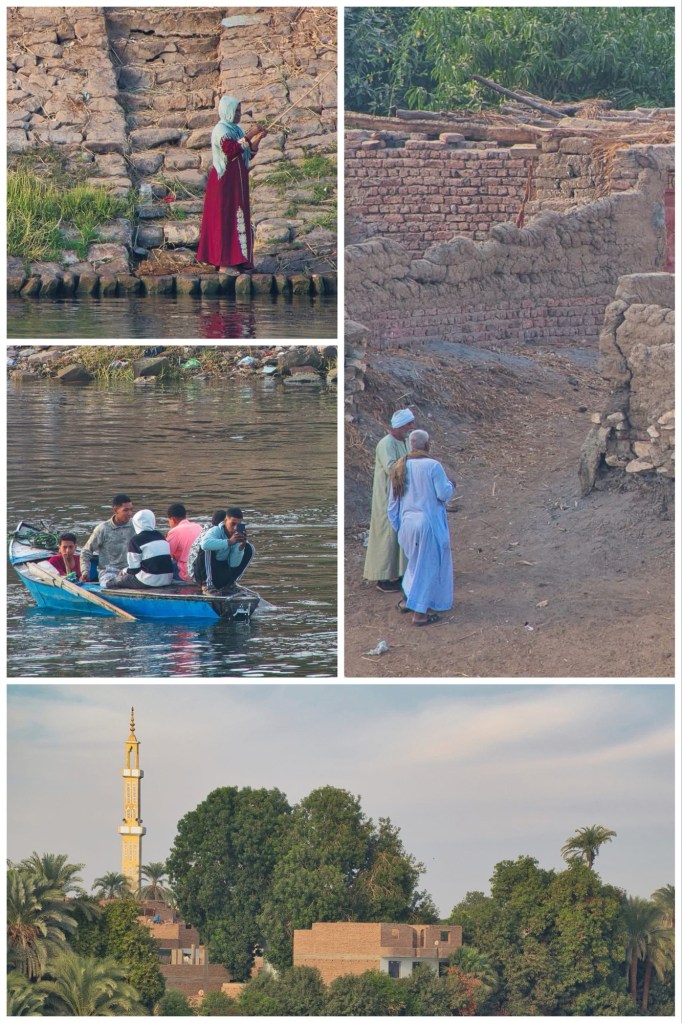

Ted took some wonderful photos of life along the Nile while I was busy writing.

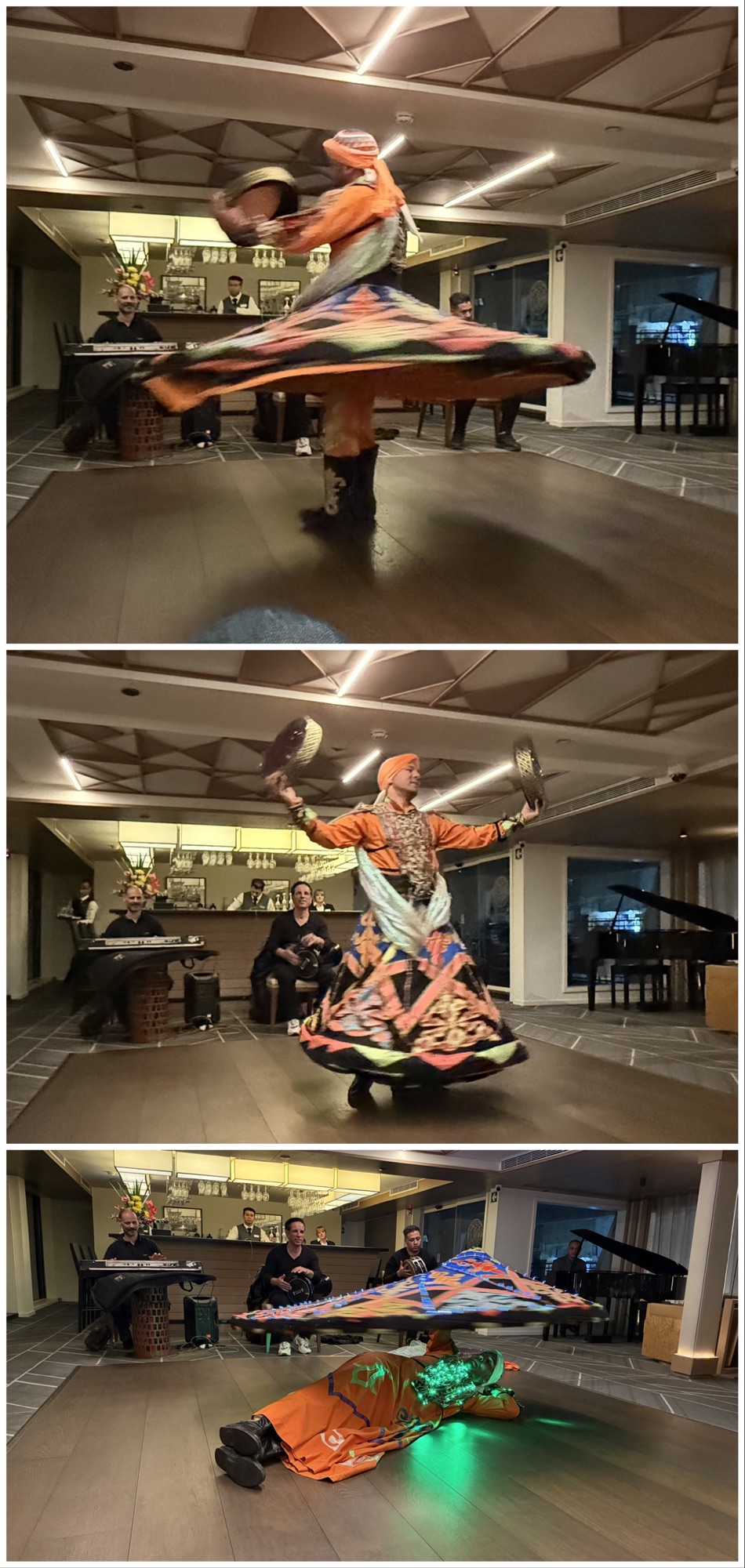

After dinner with the two Australian couples whose company we’ve been enjoying (the 6 of us comprise the cruise’s “Commonwealth table”) Viking had a surprise for us: a destination performance by a dervish dancer, accompanied by traditional Egyptian instruments. While the dancer was not an actual Sufi ascetic, he was very talented and very entertaining.

Tomorrow is a thankfully less strenuous day, with just a short walking excursion to the ancient temple in Esna, followed by a day of sailing to Aswan. Naturally, there are lots of activities being offered: a cooking demonstration, a wheelhouse tour, a talk on hieroglyphics, and an afternoon tea – but we can take things as easy as we like. There’s a very lovely and comfortable top deck where we might just choose to sit and watch the Nile waters.

Excellent report for Egypt Day 6 Rose!

I was wondering if all the tombs have stairs and railings?

LikeLike

At the Valley of the Kings those tombs that are available to tour have all been made very “pedestrian” friendly. A combination of ramps and stairs, all with railings, and tall enough to stand upright everywhere.

The tombs of Sakkara are narrow, ramped, and require bending low.

LikeLike