This morning’s specialty breakfast pie was sour cherry with elderflower infused whipped cream. Ted, not being a fan of cherries, had pancakes and bacon. There’s also a specialty local egg dish each day, but … pie!

Having this hearty dish for breakfast means we’re really not terribly hungry for lunch. After yesterday’s minced meat banitsa, Ted and I only had iced tea for lunch, and shared a very small piece of delicious tres leches cake.

After breakfast, Ted and I did an excursion together, and then in the afternoon I headed off on my own to bake!

The morning tour was called “Vidin on Foot”.

Vidin is one of the oldest cities in Bulgaria, and has a glorious past. It was the capital of the Western Bulgarian Kingdom for about 30 years prior to the 5 centuries of Ottoman occupation, but its history goes back to its founding as a Celtic settlement and later a Roman stronghold.

This is clearly a community very proud of their waterfront. It already comprises historic sites and gardens, and is in the midst of a three year project of further expansion.

Still, the town shows the effects of both Soviet and post-Soviet era policies: the relocation of people to industrial centres during the former, and the economic effects of the loss of Russian markets after 1989. At one point 75000 people lived here; today the population is just over 30000.

Nonetheless, the many landmarks highlighted on our walking tour spoke to a long and rich history.

The first monument we passed was the Memorial of the Victims of Communism.

The city’s theatre was built before electric light, so was constructed with a glass roof to allow daylight to enter. Lanterns were used in the evenings.

The Inner Wheel Club building was built in the early 19th century as an officers club but is now an art museum, with free admission to the public.

A current hotel was originally a Turkish bath house, and continued in operation in that role well into the 1980s!

The low stone wall along the river dates to the beginning of the 18th century, constructed as both a fortification and a breakwater to protect against flooding of the Danube. In 1942 a flood destroyed 2/3 of the town. That was part of the impetus for the much-delayed addition in the 1970s of iron plates which can be raised to increase the wall’s height during extreme high-water events. The plates have apparently never been used; in 2004 a less severe flood did not require their deployment and there was no damage to the town. We treated them as a waterfront sidewalk.

We passed a portion of one of the city’s 5 stone gates – the biggest one is called telegraph gate, and was originally used by the customs office of the port.

We could see the bridge spanning the Danube allowing Bulgarians easy access to Romania, something not permitted in the Soviet era. The statue looking across the Danube predates the bridge, so may be stoically longing to cross.

The two storey stone post office has vaults in the basement where people used to keep their gold.

We walked to the “Triangle of Tolerance,” where St. Nicholas Orthodox Church, the neo-Gothic Vidin Synagogue, and the beautifully preserved Osman Pazvantoglu Mosque live harmoniously side by side in a celebration of multiple faiths.

The large red house with a stone and tile private chapel in its yard is the residence of the bishop of Vidin, who was recently elected as the Patriarch of Eastern Bulgaria.

Opposite the residence is the mosque, built at the beginning of the 19th century.

In the Ottoman period there were 26 mosques in the city, but so many were destroyed after the 1877 liberation that only 4 were left by the mid 1900s. Of those four, 3 were destroyed by the Soviets.

Beside the bishop’s residence is the Eastern Orthodox Church built after Bulgaria’s liberation, and behind it remains a a much smaller church (“no taller than an Ottoman on horseback”) built in the middle of the 17th century.

The impressive Synagogue of Vidin was newly rebuilt in just the past 3 years. The original was designed by a Hungarian architect and built in 1894 after Bulgaria’s liberation. During the Soviet era it was turned into a warehouse, then intended to be renovated into a music hall due to its good acoustics, but when funds ran out while the roof was being repaired it was destroyed by decades of weather incursion, and overgrown by vegetation. The synagogue’s recent rebuilding was done using EU funds. Currently Vidin has only 25 Jewish residents, who only sporadically use the building, so it is used as the “home of culture” hosting concerts and events attended by the wider community.

We noticed the tablets representing the 10 commandments high above the entrance.

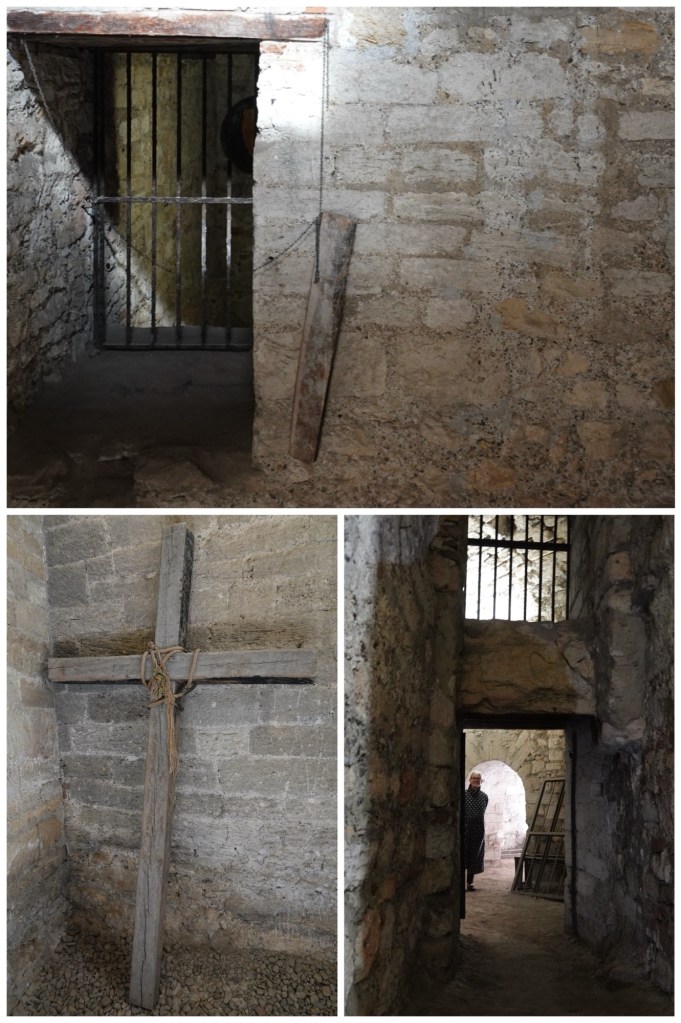

Our featured destination was the best preserved mediaeval castle in Bulgaria, the Fortress Baba Vida (literally “Granny Vida”). This 10th-century medieval fortress was the main defensive structure during the Middle Ages and is the symbol of Vidin.

The low building opposite the fortress is a museum holding sarcophagi, tombstones etc from the city’s Greek, Roman, and Ottoman periods.

The legend of the Baba Vida castle is that there was a very rich man with 3 daughters who lived in this part of Bulgaria. His 2 elder daughters married unhappily and eventually both went to live in a monastery. His third daughter, Vida, did not marry and used her inheritance to build this castle and do wonderful things for the people of the area.

The legend is unverifiable.

The structure itself is a 10th century keep with 2 concentric outer walls, multiple towers, and a moat that was once filled with water from the Danube.

On the map below, white represents Ottoman construction, red is Bulgarian, pale yellow is Habsburg Austrian. The Roman fortification in the city was rectangular and would have completely encompassed Baba Vida.

We were able to cross the cobblestone bridge into the fortress/castle courtyard, surrounded by stone chambers containing various historic displays, including clothing, armour, and weaponry.

From the fortress, we walked into the pedestrian mall in the centre of the city, past the X-shaped Ottoman barracks (now a museum)…

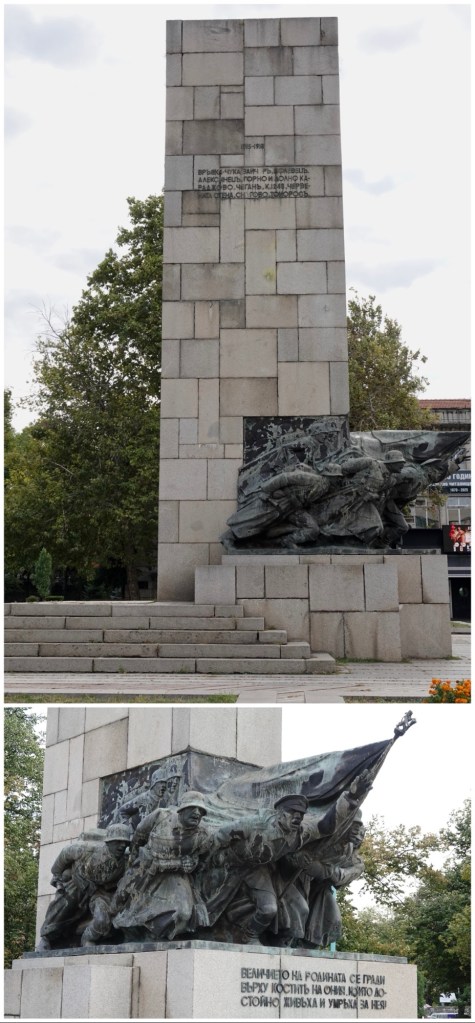

… the memorial to Bulgarian soldiers who fought in the 4 wars that bracketed the turn of the 20th century…

… noted some Austrian-influenced architecture …

… and strolled back to our ship via the Istanbul Gate, which would once have led to the road to Constantinople.

Then, in the afternoon while Ted rested (he has somehow developed an energy-sapping head cold), I headed off in a group of 16 passengers to a home-hosted cooking demonstration: The Fine Art of Bulgaria’s Celebrated Banitsa Pastry.

Banitsa is a bit like Turkish burek, a bit like Serbian gibanica, a bit like Greek spanakopita, and a lot like my grandmother’s Hungarian version of savory (cabbage, carrot, or cheese) strudel, in which the layers and layers of tender, translucent dough surrounded a shredded filling. It is often referred to here simply as “pie”, in a marked departure from the filled crusts we call by that name, similar to the way in which “pudding” in England means something very different than it does to North Americans.

We drove with our guide to a home near Vidin, where we were greeted by our hosts Nicolina and Yuli with a shot of home-made quince rakia followed by tea made from the flowers of their own lamb’s-ear plants.

This is one of the unique “up close” experiences that Viking offers, but which we’ve never done with them before. Our hosts did not speak any English, but our guide Krasimir, who was a chef on Viking’s river ships before Covid and now works closer to his home teaching culinary classes at Vidin’s high school and acting as a tour guide, translated.

I was excited to see how Bulgaria’s banitsa is prepared, and to see how the process compared to my grandmother’s strudel dough making, but the demonstration was about assembling and baking the dish, not making the dough. Krasimir explained that phyllo dough is simply flour, water, and vinegar, beaten completely smooth and then rolled and stretched to translucency over a cloth-shrouded table. Nikolina verified that virtually no one makes it from scratch anymore now that good quality dough is readily available in grocery stores.

But I digress.

Our hostess has been baking banitsa for over 50 years; it is a staple of the Bulgarian diet, and absolutely essential at every celebration.

One of the things I found so interesting was the measuring of ingredients. My grandmother’s strudel used to measure in “cups”, but her cup was a Corningware teacup. Nikolina’s recipe was in cups too, and she showed us her measuring cup: a 12 oz coffee mug, into which she would pour “three fingers” of liquid ingredients. It’s a good thing making banitsa filling is not a precise process.

Here’s the recipe that she demonstrated, and that several of us got to recreate for the second pan. She used a 40cm/16 inch diameter high-rimmed stainless steel pan, but a 9 x 14 inch deep-sided rectangular cake pan would work for this quantity of ingredients.

Nikolina’s Cheese Banitsa:

- 500g pkg of frozen or refrigerated phyllo dough, in sheets

- 6 eggs

- 300 g (approx 3/4 lb) dry feta cheese, coarsely crumbled

- 1/2 teacup 😊, equal to 3/4 cup in real measures, plain Balkan style yogurt

- 1/2 teacup 😊, equal to 3/4 cup in real measures, sunflower or canola oil (any good vegetable oil – not olive oil, which tastes too strong)

- 1/2 teacup 😊, equal to 3/4 cup in real measures, “fizzy drink”. She used a local carbonated lemon drink, but 7Up would work, or even sparkling water. It’s the carbonation that matters. Important: don’t drink the rest of the can or bottle – you’ll need it later!

- 1 heaping coffee spoon 😆, or one standard tablespoon, of baking soda

- 1/2 stick (1/8 lb) of unsalted butter, chilled and cut into small cubes

Thaw the phyllo in the refrigerator if necessary, but leave it chilling until everything else is ready.

Preheat the oven to 180°C/350°F

Stir the baking soda into the yogurt to make it thicken and foam slightly.

In a 2 litre/8 cup bowl, break up the eggs with a fork. Add the crumbled feta, oil, and carbonated liquid and stir – by hand – to mix. It will be quite liquid in texture. Stir in the thickened yogurt to blend. The mixture will be thicker, but should not be smooth. Set aside.

Next, generously grease your pan with oil.

Here’s where it gets interesting: lightly CRINKLE 2 sheets of phyllo over the bottom of the pan. If the phyllo has been too long at room temperature, it will completely fall apart; chilled phyllo is slightly sturdier.

Using an ordinary tablespoon, drizzle/drop about 3 tbsp of the filling sparsely over the dough. Too much on this bottom layer and it will get soggy.

Crumple another 2 sheets of phyllo over the filled layer, turning the sheets at right angles to prevent leaking. This time, add 6-7 tablespoons of filling, dropped over the pastry. Repeat, using all but one sheet of phyllo and laying each layer at 90°angles to the previous one.When there is only one sheer of phyllo left, use up whatever filling is left, and cover the entire thing loosely with that last sheet, tucking it in lightly at the sides. (Magically, filling was exactly the right amount for the number of sheets in the 500g package – I think there were 15.)

Since you won’t have drunk the extra “fizzy drink”, pour about 3-4 ounces over the top of the “pie”. If it seems like too much, tip the pan so that some runs down into the sides of the pastry. There should be a wet sheen, but no pools of liquid.

Dot the top with butter.

Bake for 30-40 minutes.

Check at around 20 minutes. If the top seems to be browning too fast, cover it with a sheet of parchment paper sprinkled with water.

Here’s the ridiculously delicious finished product:

This is a great recipe to experiment with. If you omit the yogurt, baking soda, and fizzy drink, you can combine the eggs and cheese with spinach, leeks, ham, shredded potatoes, shredded cabbage or squash to make a variety of savoury banitsa. Add nuts, raisins, or cinnamon, nutmeg, or even a touch of sugar.

We were given a second recipe for a sweet strudel-like banitsa.

We learned that sometimes the baker inserts a “lucky charm” (a wish written on paper and sealed in foil) into the dough before baking so it can be discovered later. Surprise!

As our banitsa baked, we sampled the local yogurt and learned how to curdle our own. Bulgarians love yogurt, and claim it is why so many of them live to be 100 years old.

It’s easier than we’d imagined. Akin to using a sourdough starter, you just need a “starter” of some really good quality yogurt that has no sugars, flavours, or additives. Stir 2 tbsp into 1 litre of fresh milk, and set aside for 6-8 hours at a constant temperature between 45-48°C/110-120°F – the temperature of an oven light or a proofing drawer! After that, chill the thickened milk for a couple of hours – long enough to bake some banitsa to be eaten with yogurt and honey!

After our cooking lesson, we got a quick tour of the herb and fruit gardens, and the summer kitchen.

It was a lovely glimpse into the lives of this retired couple who left their busy real estate careers to make rakia, keep bees, and teach tourists about traditional Bulgarian food.

The “destination menu” dinner tonight continued our adventure into tastes of the Balkans. The dishes were perhaps not as pretty as usual, but all were delicious.

Tomorrow we’re headed into the 80km stretch pf the Danube known as the Iron Gate, headed into Serbia.

FOLLOW-UP:

A couple of weeks after we got home, I decided to make a batch of banitsa using the recipe we’d had demonstrated. I couldn’t find dry feta (everything came in brine), so used shredded feta. In place of the Bulgarian lemon-lime fizzy drink I used Sprite, and I used Canadian Astro brand Balkan style 3% fat yogurt.

By choosing phyllo pastry imported from Greece I had a choice of thin or medium. The thin is more suitable for baklava; medium is used for “pies”, a term we heard used to describe these strudel-like dishes in every country we visited (until we got to Hungary and Austria).

I used a high-sided 9” x 12” rectangular pan in place of the 14” round pan our host used. That nicely used the 11 sheets of phyllo in the package, but I ended up with just over 1 cup (250ml) of excess filling that – based on the amounts used in each layer during our demo – I chose not to use. If the package had been 15 sheets instead of 11, the amount of filling would have been perfect.

After baking for 35 minutes, here was my end result:

The verdict? Delicious!! The only thing I would change is trying to find an authentic salty dry feta, or adding a pinch of salt. I was glad that I hadn’t used the excess filling, because the pastry:filling ratio was spot on.

How did hers compare to your grandmother’s?ClayFollow and keep up with our retirement adventuresInstagram: @ClaynMike

LikeLike

Despite making it using a completely different process, and commercial dough, I have to admit it tasted almost as good!

LikeLike

I have started following your blog since we are also World Cruisers with Viking… 2019 and 2024. It’s been so much fun to see your take on many of the things that we also have seen. Would you recommend this home visit? I usually like Viking’s cultural experience but not sure about this one as it look like it was mostly just cooking. Would love your thoughts. Thank you so much and again I’m loving your blog!

LikeLike

First, thanks!

This was our first Viking home visit, so I have no basis for comparison, but this one was almost entirely cooking (and advertised as such)

LikeLike

That guy with the big shield and boots looks a lot like Ted. 🙂

And thank you for knowing that “the whole comprises the parts,” and not the other way around.

LikeLiked by 1 person