In the afternoon, our optional excursion was called “Insight into the Palace of Parliament”, described as: Explore Bucharest’s Seat of Power. Walk through the halls of the third-largest administrative building in the world, known as “The People’s Palace.”

We were reminded to carry our passports for access into the parliament buildings.

Intended to be the headquarters of Romania’s government, and built by the country’s communist dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu, the palace is surpassed in size only by the Pentagon and the new Taiwanese parliament. Beginning in 1984, it took more than 20,000 workers and 700 architects seven years to build this colossal structure; however, Ceaușescu did not live to see its completion, as he was executed on Christmas Day in 1989.

A quick detour here:

I’d forgotten the year of Ceaușescu’s execution. In 1980, while I was working for Hayward Gordon, a Canadian company who supplied the demineralized water pumps for the CANDU nuclear power reactors, Romania was one of Canada’s clients, and one of mine since I was the company’s sales representative for their nuclear-related products. In my sales role I had spent several days with a Romanian engineer and his entourage of two very silent, very large, very intimidating “associates”, who it was no secret were members of Romania’s Securitat, their equivalent of KGB agents. In one of our rare private moments, the engineer told me that his family were effectively under house arrest until he returned from Canada; “insurance” that he wouldn’t defect.

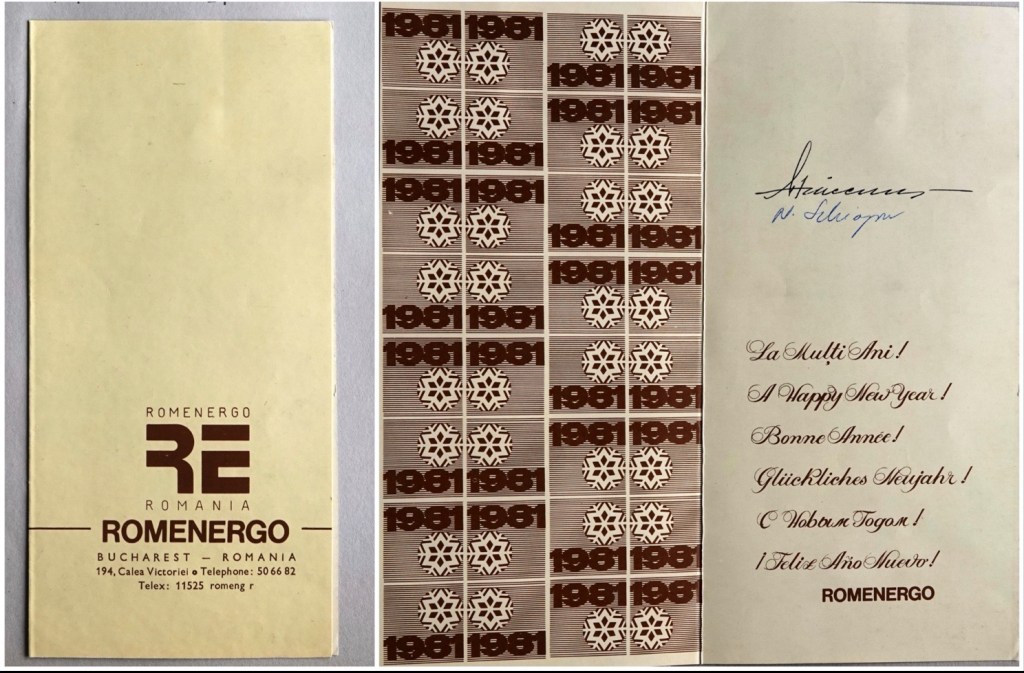

Imagine my surprise when early in 1981 I received a New Year’s card signed by Ceaușescu and his Deputy Minister of Energy. While I didn’t keep my physical scrapbook of keepsakes, Ted did take photos of them, which means we were able to retrieve the photos of that card to include here. Just look at all those postage stamps!

By the way, the reactor, finally completed in 1994, and with its partner is still operational and providing almost 1/4 of Romania’s energy needs. We should see it en route to Constanța tomorrow.

Now back to our excursion.

We had an ideal group size of just 12 people for our palace tour.

It’s sobering to realize that 80,000 people were displaced after the 1977 earthquake to create this complex of buildings – which included our hotel, originally built as a hotel to house the dictator’s guests. The people were moved from their homes into typical Soviet brutalist architecture apartments. Churches, monasteries, and synagogues were all razed to fulfill the dictator’s dream of an imperial-looking complex of buildings.

The palace actually sinks about 2.5 mm per year due to sheer weight of the building materials. The building weighs 4.1 million tonnes, which includes 1 million cubic metres of marble, 250,000 square metres of carpeting, and industrial gold.

The total building area is 365k square metres (almost 3.8 MILLION square feet) which makes it the third largest in the world, behind the Pentagon and the new Taiwanese parliament.

Once through passport checks and security screening, we were standing between a floor and ceiling of the entry hall, which are mirror images of each other, and are copies of an old Greek mosaic in Constanta.

And me, for scale.

An entire mill was created just to make Romanian crystal, since Ceaușescu’s would not accept bohemian crystal; everything had to be Romanian. The many hundreds of crystal chandeliers and lighting in 1200 offices require an equivalent amount of electricity to 1/4 of the entire city. Many of the offices are empty, and the stunning building is never fully lit.

Absolutely every inch of this gigantic building reflects 100% Romanian craftsmanship.

The “Committee of the Senate” room has 13 permanent seats arranged in a circle. The 135 Senators are elected by the citizens., but the committee is similar to the Cabinet in Canada’s system. The walls are of oak, and covered with silk wallpaper. We were reminded that ALL of the artisans involved in the creation of this building – marble carvers, wood carvers, architects, etc – were Romanian. Despite the hundreds of empty offices, Senators do not have offices in the building; their offices are in their home constituencies. There are, however, press cubicles where members of the press can meet with senators.

Romania’s government was an elected parliamentary system beginning in 1866, but universal suffrage came only in 1921, and then elections were really moot between WWII and 1989, since their results were preordained.

Meeting chambers can now all be rented to help offset the massive costs of building maintenance.

The palace was built with a specialized ventilation system, but no AC since Ceaușescu was paranoid about being poisoned. Our guide, George, pointed out some of the vents 30ft/10m up in the corners of the ceiling.

We toured the 1044 square metre (11,240 sq ft) room with a magnificent glass and gilded ironwork ceiling, which is the room in which senators are sworn in, just outside the actual senate chamber.

This staircase is labelled with the rights that Romanians now hold to be inherent: life, health, privacy, freedom, family, education, work, religion, etc. These rights were also supposedly guaranteed by the soviets in their time. Words are cheap.

We got a quick lesson in Romanian politics while we visited the main government chamber with its magnificent green marble walls that were a gift from the Shah of Iran.

The ceiling was dropped in by military helicopters and cranes. The white, blue, and green ceiling is ringed with incredibly ornate gold metalwork. This chamber was the last thing completed in the building, long after Ceaușescu’s execution.

There are 135 senators, elected every 4 years, each representing 168,000 inhabitants.

After our coffee and croissant break, we headed to a lower level of the palace, which was slightly less opulent but still impressive. Fewer of the chandeliers were lit, but ceilings still soared 10 metres high.

We entered a sculpture hall with green carpet, where George took the time to share his own experiences living here (he was 24 at the time of the 1989 revolution).

He started by talking about Romania as an agricultural powerhouse which during the Soviet era could not even feed its own people. No heating or transportation fuels, no electricity, no food, no toilet paper, no soap. Not even bread or potatoes. In the 1970s Ceaușescu borrowed money from international banks to buy technology and build Romanian industry, but countries were only selling outdated tech to Soviet bloc countries, so the big industrial boom never happened. In order to pay back those loans, he sold the country’s fuels and food. People in the cities, living in communist apartment blocks, were starving in the dark, and all the while Ceaușescu was building his marble “palace”.

On the other hand, George admitted that Ceaușescu, with only his 4th grade education, managed to be an influential player on the international stage: a friend to both the US and China, Israel and Palestine, advocating for peace in a way that leaders of small countries today would not be able to do.

We also got to see Rosetti Hall, intended as a concert hall featuring a seven ton (!) crystal chandelier. It was never used for its intended purpose, because Ceausescu was overthrown before the building was completed.

In an upper hall dedicated to media booths were exhibits of traditional early 20th century Romanian costumes from various regions of the country.

The Hall Of Human Rights, the last of the palace’s more than 1100 rooms that we were allowed to see, is so named because it hosted the first meeting after the revolution. The furnishings are original to the Soviet era when it was a committee room. Its crystal and brass chandelier is the building’s second heaviest, at 3000 pounds.

We ended our tour realizing that over the course of its long history, Romanians never seemed to be able to win, whether it was under Ottoman rule, suffering devastating earthquakes, choosing to side with the Nazis, or eventually aiding the Allies only to end up a Soviet bloc holding.

We also realized that they are a resilient nation, looking forward hopefully to a bright future.

Btw Trump is visiting England tomorrow.A comment made … The Queen had to see Ceauşescu the King can see trump lol

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating and appalling in equal measure! My main memory of news out of that era is the the starving children in Ceauşcu’s orphanages. It’s interesting that these dictators still want the trappings of democracy — a representative parliament. They need to pretend that the people wanted them to rule. A new ballroom started construction in our capital this week — I hate the style and everything about it. Do you think the Romanians would tear down that building and repurpose the materials if they had the means to do so? It must be hard to be reminded of Ceauşescu. Maintenance must take a bundle. How interesting that you had contact with that government. It’s great that the reactor is still working well! Since Romansch is a latinate language, were you able to make out any street signs or menu options? Thanks for the details, always.

LikeLike

There were definitely some words that looked familiar – as if they were Italian, or in some cases French. The Romanians use “merci” for thank you as often as whatever the Romanian word is, and “buna sera” for good evening, which is pretty much buona sera!

LikeLike

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Sadly, no comment came through…

LikeLike