Knowing we were docked in Vigo (pronounced “Bigo” by the locals) from 8:00 a.m.until just 4:00 p.m., we chose this as our opportunity for a Viking excursion to Santiago de Compostela to see its stunning cathedral and tour the Old Town. That meant not having time to explore Vigo’s lovely belle epoque neighbourhoods, but choices have to be made!

Vigo is Spains’s largest frozen fish processing region; Coruña, which we’ll visit tomorrow, is the largest fresh fish processor. Of the three major cities in Galicia it is said that “Santiago prays, Vigo works, and Coruña plays”.

Santiago de Compostela is not only the home of the famous cathedral of the same name, but is the capital of northwest Spain’s Galicia region.

We had another wonderful guide today, Goncalo (pronounced GonTHalo), who regaled us with the region’s history as we drove past inlets full of eucalyptus-wood mussel platforms (Galicia is Europe’s main producer of mussels), vineyards with raised trellises to keep the white Alvariño grapes from getting too wet…

…and the city of Ponte Vedra (“old bridge”) with its picturesque marina. “Gon” told us that Ponte Vedra has a stunningly beautiful old city, but it is surrounded by post-Spanish Civil War “ugly” architecture.

We also got a brief history of Galicia, which was originally settled by Iron Age Celtic tribes. Blame their 4000+ settlements over 30,000 square kilometres for the fact that the area’s most traditional musical instrument is the bagpipes! The Romans followed in the 3rd century, looking for gold and tin. In the 4th century, Swabians (Germanic people) arrived, having been pushed out of their homelands along the Danube by the Huns. They saw themselves as exiles/refugees. The Romans saw them as invaders. The Visigoths took over in 585CE, the Islamic Moors in 718, and by 740 it was back to being Christian under the Asturians. After a period of relative autonomy under a succession of Castilian kings, it’s no wonder Galicians don’t necessarily think of themselves as “Spanish”.

There are 4 official languages here: Galician, Catalan, Basque, and Spanish. The gastronomy is also more “Atlantic” than southern Spain’s Mediterranean influences.

After all that, we were ready for Santiago!

The city is known as the culmination of the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route, and is the alleged burial site of the Biblical apostle St. James (called both Santiago and San Diego in Spanish). His remains we’re supposedly brought here by boat after his beheading in 44CE by King Herod Agrippa of Judea, and buried under a marble slab. His grave was “discovered” in the 9th century by a monk led to the spot by a “field of stars” (compostela in Spanish).

An altar was erected over the gravesite, and pilgrimages began soon afterward, but it was not until Pope Leo XIII issued a papal bull in 1884 proclaiming that the relics at Santiago de Compostela were indeed those of St. James that the pilgrimage tradition that had declined during the Protestant Reformation was revitalized. Toward the end of the 20th century it became known as the Camino de Santiago (Spanish: Way of St. James). In the 21st century the tradition has continued to grow, encouraged by Pope John Paul II among others, and the shrine of St. James now attracts more than 200,000 pilgrims from all over the world each year, with an annual growth rate of more than 10 percent.

Ted and I are not here on a pilgrimage of either faith or penance, and will be expecting no papal indulgence for our visit, since it definitely did not involve any hardship or sacrifice to get here.

For me, it’s all about the history and architecture.

We arrived on foot from the bus station via a typical mediaeval era street.

When pilgrims arrive at the cathedral, they are greeted by the skirl of bagpipes.

The building of the current cathedral started in 1075 CE and it was completed/consecrated in 1211. It was originally Romanesque, built of granite but with marble entry columns, but many different architectural designs have influenced the facades over the past 1000 years. There are both Gothic and Baroque elements to the cathedral today.

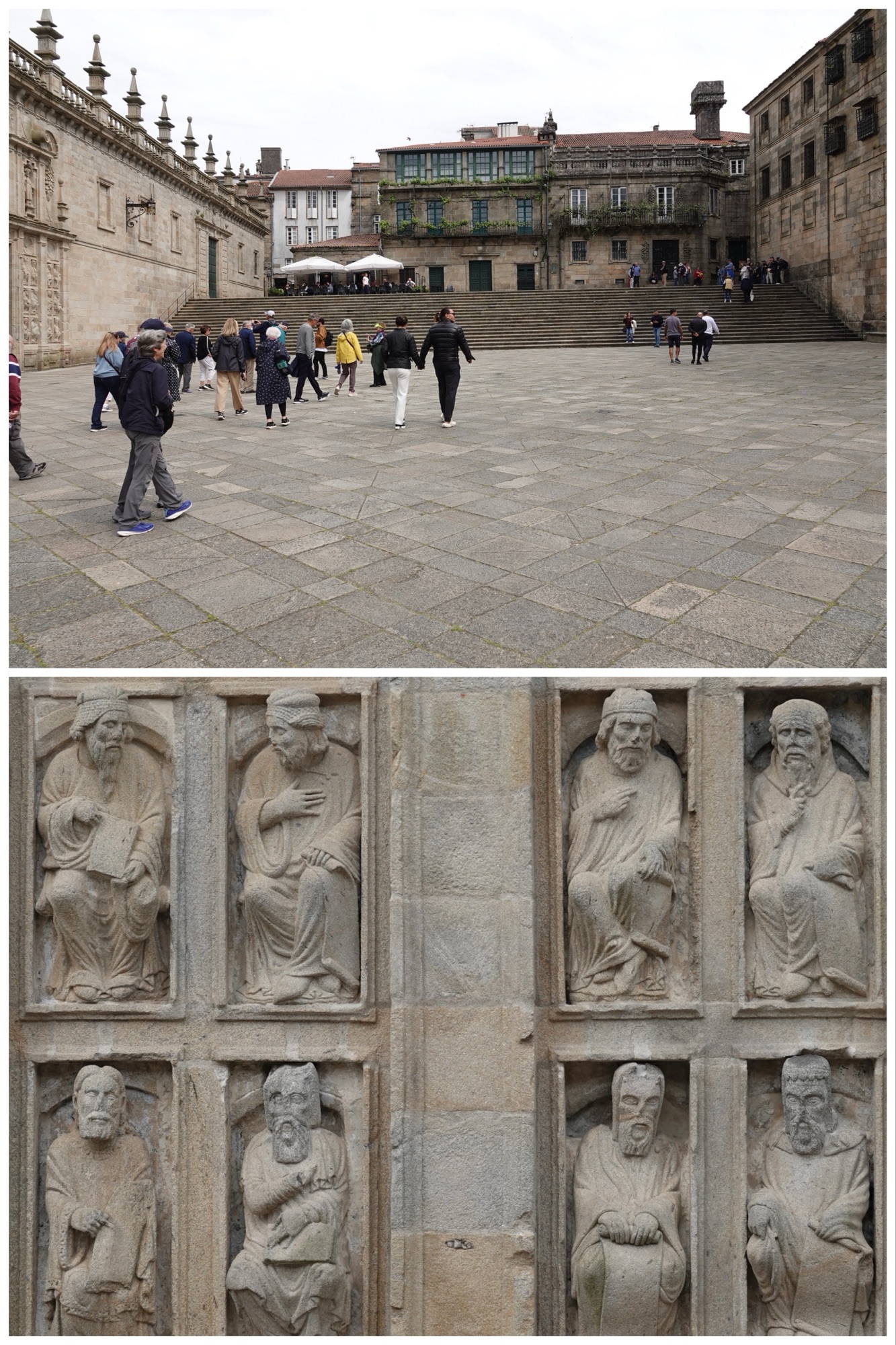

The cathedral’s elaborately carved stone facades open onto grand plazas within the medieval walls of the old town.

In the centre of the Plaza del Obradoiro (the “working” square because it is where artisan workshops , smithies, shops, market stalls, etc would have been set up) is kilometre zero of the Camino. A shell carved into the granite marks the spot.

Originally, pilgrims were given a scallop shell, the symbol of St. James, at the end of their trek, but it was too easy for people to simply pick up a shell on the beach (or in a restaurant) and claim the feat. Nowadays pilgrims get a shell and a certificate once they have completed at least 2 stamp-verified checkpoints per day in their Camino passport, plus a total distance of 100 km on foot or 200 km cycling. The “passports” are available at any St. James church in Europe.

On the other 3 sides of this square are the Seminary (now City Hall), the Archbishop’s Palace (now a 5-star Parador Hotel), and the Romanesque rectory (now a university museum).

We learned, and saw, that St. James is depicted in three different ways: as an apostle, as a pilgrim, and as Santiago Matamoros (Spanish for “St. James the Moor-Slayer”). He was depicted on horseback, brandishing a sword, and even with dead Moors at his feet – iconography that served to inspire Christian knights in battle against the Muslim Moors during the Crusades. The latter depiction is bizarre in the extreme, and evidence that propaganda was alive and well long ago, since James died well before the advent of Islam (founded around 610CE).

Before entering the cathedral, we toured the Museum housed in a Gothic cloister. No photography was allowed in the museum, but among many other things we saw:

- 13th and 14th century statues, icons, piétas, paintings, and triptychs donated by nobles and pilgrims from all over the states that now comprise Spain and Portugal

- More statues of a pregnant Virgin Mary

- Cathedral bells that were supposedly stolen by Almanzor (the ruler of Islamic Iberia until 1002 CE) in the 11th century and retrieved from Granada during the crusades

- Illuminated codices dating from 1139-1165CE

- Tapestries from the 1600s, including one belonging personally to Charles III of Spain

- A reproduction of a huge 12th century incense burner

When we exited the museum, there was an Austrian Männerchor (male choir) from South Tyrol practicing hymns while taking advantage of the amazing acoustics of the cloister’s gallery. We learned that they had just completed a group pilgrimage, and were headed into the cathedral for mass.

It was finally time to go inside the crowded cathedral.

Goncalo pointed out the “Portico of Glory” comprised of three arches allowing light into the cathedral, based on the premise in Revelations that at the end of the world there will be a bright light. WAY up at the top was an image of the Lamb of God.

We viewed the visible portions of the more than 3000 pipes of the cathedral’s organ…

…and the giant silver thurible (incense burner ). In early days, incense was needed to overpower the smell of hundreds of unwashed pilgrims congregated in the cathedral. No photo, because we were being rushed through to avoid interrupting mass.

We gaped at the main altar, with (if Goncalo’s’ research was correct) its more than 2000 square metres/21,500 sq ft of gold leaf and gilding.

Because of that mass that was about to begin, we were hurried into the crypt below the altar where the saint’s body is interred in a sepulchre covered with gold. The crypt walls are the original Roman walls from the first burial chapel.

From the crypt, we were allowed to quickly walk behind the altar, where pilgrims – and tourists – are allowed to hug a statue of St. James. No photos allowed – it’s not supposed to be an Instagram moment. And no, I didn’t.

We were virtually “ushered” out of the cathedral as mass began. Goncalo gave our group the option of free time (not included in the excursion description) or a walk around the squares surrounding the cathedral. Naturally, we opted for the latter.

In the “Silver Square”, we saw the “horse fountain”. Gon explained that they are not horses, but rather seahorses. That’s because a myth arose that the boats that brought Saint James’ body to Santiago were pulled by seahorses. Apparently it’s a university prank to send freshmen looking for the horses’ genitals and then push them into to fountain when they can’t find them.

Behind the horse fountain is a lovely Baroque facade that is just that: a facade with no building behind it. it was erected solely to give the quadrangle symmetry.

The “silver facade” of the cathedral facing the square features 13th century expressionless statues that were modified into Gothic era faces with emotions.

To the left of the fountain from our vantage point was the Museum of Pilgrimage, built in what would later be considered typically eclectic mannerism-style architecture.

The second square to which Gon led us was the Quintana de Mortos (square of the dead) which is a stone quadrangle built on top of the original cemetery yard located here.

The Baroque facade here dates to the very early 18th century, when the original Romanesque facade was updated to compete with the Vatican.

The “Holy Gate” (below) is opened only during Holy Years, when the July 25th date of Saint James’ death falls on a Sunday.

In a third square, the cathedral’s “jet facade” was visible. This was the original entrance to the cathedral for pilgrims, who would exit through the door in the silver facade. Entering through black jet and leaving via silver was meant to represent a journey from darkness into light, sin to purification.

Opposite the jet entrance is a massive former monastery and seminary that is still a hostel for pilgrims.

We both felt we could have spent MUCH more time in the cathedral and its squares.

Our group’s coffee break was at the Hostal de Los Reyes Católicos (“Hostel of the Catholic Monarchs”), a former hospital and now a luxury Parador hotel. It reminded me that I’d love to do a tour of Spain’s 97 Parador hotels, all located in historic buildings.

We returned to the ship mid afternoon, ready for coffee and an early sail-away. Our day ended in the Chef’s Table where our meal concluded with this gorgeous dessert:

We’ll have one more day in Galicia tomorrow, in A Coruña.

Your post brought back many wonderful memories of the post-cruise extension we took with Viking, after our Douro River of Gold cruise, in 2016. We took the same route, Vigo to Santiago, so your photos of the mussel flats and other scenes were so familiar!

Santiago de Compostela is an amazing place, we had two evenings and a full day there, with two walking tours and free time to explore. I even have video of Galician bagpipes. Thank you for the memories!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your post brought back many wonderful memories of the post-cruise extension we took with Viking, after our Douro River of Gold cruise, in 2016. We took the same route, Vigo to Santiago, so your photos of the mussel flats and other scenes were so familiar! Santiago de Compostela is an amazing place, we had two evenings and a full day there, with two walking tours and free time to explore. I even have video of Galician bagpipes. Thank you for the memories!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed this post as we will be spending a week in Santiago de Compostela this June as our daughter has decided to get married there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a lovely venue choice! Lucky you!

LikeLike