Our first impression when we got to Singapore at the beginning of March was a sigh of relief at its cleanliness and comfortable modernity. This, after all, was what we expected a world-class city to look like.

There was no “visible” poverty on our tours there, just a modern incredibly clean city devoid of traffic jams or slum areas, that had also managed to retain its history.

There’s no question that Singapore is wealthy. Under the leadership of Lee Kuan Yew, who leveraged its strategic location and focused on attracting foreign investment and promoting globalization, the country has become a prosperous financial centre.

Compared to almost entirely Hindu Bali and almost entirely Muslim Java, Singapore was also a multi-religious and multi-ethnic society – much more like what we’re used to in Canada.

We were amazed at its cleanliness, which was in stark contrast to Bali, Java, Indonesia, and Kenya.

We’ve never seen the amount of litter, trash, and discarded building materials on North American streets that we saw in urban Denpasar and Semarang. Even in Kenya most of what we saw was inorganic garbage and not household waste.

On the flip side, I don’t think we’ve ever been in a city as clean as Singapore.

I had to be reminded by a fellow passenger that as recently as my childhood years in the 1960’s, Canadians were still throwing trash out the windows of speeding cars onto the side of the highways, and dropping chewed gum on sidewalks, not to mention pushing empty shopping carts into creeks!

It would be facile but naive to assume that the lack of focus on sanitation services and housing standards are directly related to poverty but, now that we’re visiting the poorest continent on earth, poverty is definitely worth discussing.

As of 2023/4 census information, and using the World Bank’s definitions of extreme and moderate poverty (based on international poverty lines of living below $2.15USD and $3.65USD respectively) Malaysia and Thailand would be at a somewhat surprising 0%, Indonesian countries on average at 19%, Sri Lanka 11.3%. The numbers are different when looking at people living below their own country’s national poverty line: Malaysia 6.2%, Thailand, 6.3%, Indonesia 9.4%, Sri Lanka 14.3%.

By comparison, the national poverty rate in the USA at the same time was 11.1%, and Canada was 7.4%.

Singapore does not release national data. There is no minimum wage or poverty line set and no welfare provisions; all we have are estimates by the World Bank based on the incredibly high cost of living here, which put it at 1 in 10 families (10%) living in poverty.

When we got to Africa, the numbers jumped alarmingly, with Kenya at 70% and Madagascar at 93% based on the World Bank definition and and Kenya at 39% (with no data for Madagascar) using their national poverty level.

The differences between the World Bank numbers versus national numbers made me stop and think about how we define “poverty”. Even the poor in Bali and Java can afford to eat, have access to government-funded medical care and public education, and have a roof over their heads – even if that roof doesn’t look like what we’re used to seeing in countries with much more variable weather conditions.

Definitions of the poverty line vary considerably among nations. For example, rich nations generally employ more generous standards of poverty than poor nations. Even among rich nations, the standards differ greatly. Thus, the numbers are not comparable among countries. Even when nations do use the same method, some issues may remain. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_percentage_of_population_living_in_poverty)

Charities like World Vision (not an endorsement) define poverty as “lacking enough resources to provide the necessities of life—food, clean water, shelter and clothing. But in today’s world, that can be extended to include access to health care, education and even transportation.”

In Kenya and Madagascar, we saw roadside markets and kitchen gardens. The daily diet may be (to us) incredibly reliant on rice, or corn, or breadfruit, and whatever can be raised locally to supplement that, but it is nutritious.

We saw far fewer beggars (we actually saw none) in statistically much poorer Madagascar than we did in Indonesia. One of our fellow travellers, Joseph Purdy, commented about this in our Facebook group, saying: “Sadly, in spite of having rich natural resources, it is one of the poorest countries on our planet. We must say, that everywhere we went was super clean, and the people outgoing and friendly. And, you know how in most poor countries the children, teenagers and adults are constantly approaching you and asking for money, or trying to sell you something? None of that happened here, not once. Just greetings, smiles and a willingness for a chat and a photo.”

Water from municipal taps may not always be potable, but in Kenya we saw water delivery trucks and carts, and women (almost always women) fetching well water.

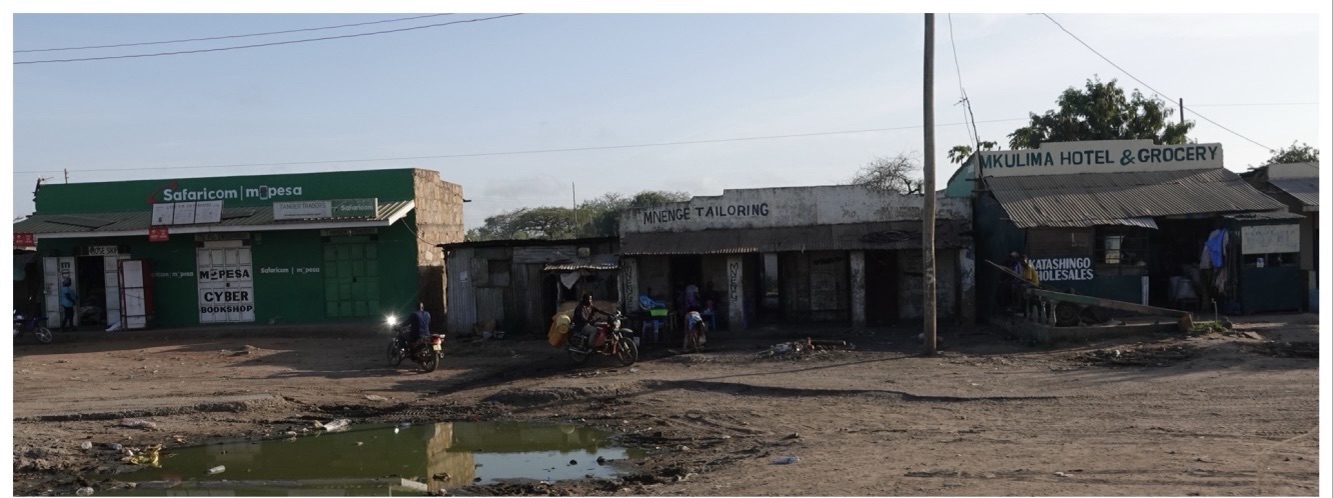

We saw looped power lines in most places, although cooking was mainly being done on propane stoves, and certainly no one was running electric clothes dryers.

Notice the hydro lines.

“Shelter” in many cases was rudimentary – glass window panes are not used except in high-rises (sometimes not even then), and doors were often just cloth curtains but, in a year round sweltering hot climate without air conditioning, solid barriers everywhere would make no sense anyway.

Everyone was cleanly dressed, although how they manage that in incredibly dusty conditions and hanging clothes to dry next to non-stop traffic on dusty roads is nothing short of miraculous. We saw children walking to and from school; education is free and mandatory from age 5 until age 17.

Tuktuks were ubiquitous, as were motorbikes and small van “buses” (although the latter were not always affordable).

Access to health care was harder to judge. We saw clinics and pharmacies, but (as in North America) rural dwellers were often far from a hospital, and we saw personally that insane traffic meant that ambulances could not always get through. We definitely saw more people with teeth missing than we’re used to, attesting to a lack of preventive dental care.

One of the things missing from the World Vision definition is sanitation, which is a really hard thing to judge from short visits. We weren’t inside people’s homes to see their bathrooms, so we can only comment on public bathrooms. All of those had plumbing. Not all of them had western-style toilets, or toilet paper. That required a real “reset”. In cultures with squat toilets and washing hoses, people who are used to that routine think toilet paper is disgusting. Imagine just wiping and not washing!! Even in places with toilets and toilet paper, the toilet paper often cannot be flushed – the “clue” is a wastebasket beside the toilet. Toilet paper clogs small sewer pipes. We experienced that phenomenon in Mexico too, even in some upscale accommodations, shopping malls, and restaurants.

That’s not a question of lack of sanitation, or of poverty, but of the age of the system.

The ancient civilizations like the Romans had advanced sanitation systems; Dark Ages Europe did not – infrastructure in general is not a great indicator of poverty. Hence, unpaved roads do not necessarily equate to “poor”. In areas with monsoon rains, bare earth may absorb water better than tarmac would.

Nonetheless, there is no question that the visible differences in lives here when compared to our very privileged lives had an impact on everyone who ventured off the ship, and left many of us asking “what can, and what should, we do?”.

It also left some of us (okay, me) angry at the very rich who aren’t sharing. OXFAM (again, not an endorsement) has a wonderful article on their website called “World’s top 1% own more wealth than 95% of humanity, as “the shadow of global oligarchy hangs over UN General Assembly”. It’s absolutely worth a read.

Tourism is going to be a boon for some of the places we’ve visited, but its impacts often only reach those few people who have had the opportunity for education in the language of tourists. Better, in my opinion, would be more countries investing less on the machinery of war and more in foreign aid and infrastructure. China is making impacts with roads, railways, ports, and hydroelectric dams. And then, in return for access to the mineral wealth of Africa, a meaningful sharing of profits and control.

It may be pipe dreams. Maybe humanity is hardwired for greed and selfishness. Maybe we always need someone less well off than we are in order to see ourselves as successful.

I really hope not.

I enjoy all of your posts and truly appreciate the time you dedicate to taking me along on your journey. Today’s post was,for me, very thought provoking. That is what made it so very special.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have been enjoying your posts. Thank you for your comments in this one.

LikeLiked by 2 people