Puerto Chiapas is the southernmost port on Mexico’s Pacific coast. It is relatively new, built in 1975, and is the primary hub from which the region’s agricultural goods, including coffee, are sent abroad.

It is situated on the Gulf of Tehuantepec, approximately 6 km/10 miles from the city of Tapachula, the second-largest city in the state of Chiapas, and is the closest port to the Guatemalan border. It is a fairly recent (2006) port of call for cruise ships.

There were dozens of magnificent frigates flying overhead as we cruised in. Ted took over 300 pictures of them!!

Coming into port the difference in the topography between Huatulco and Puerto Chiapas is striking. The area here is virtually flat as it stretches out to the ocean – no rocky coastline, and no visible mountains.

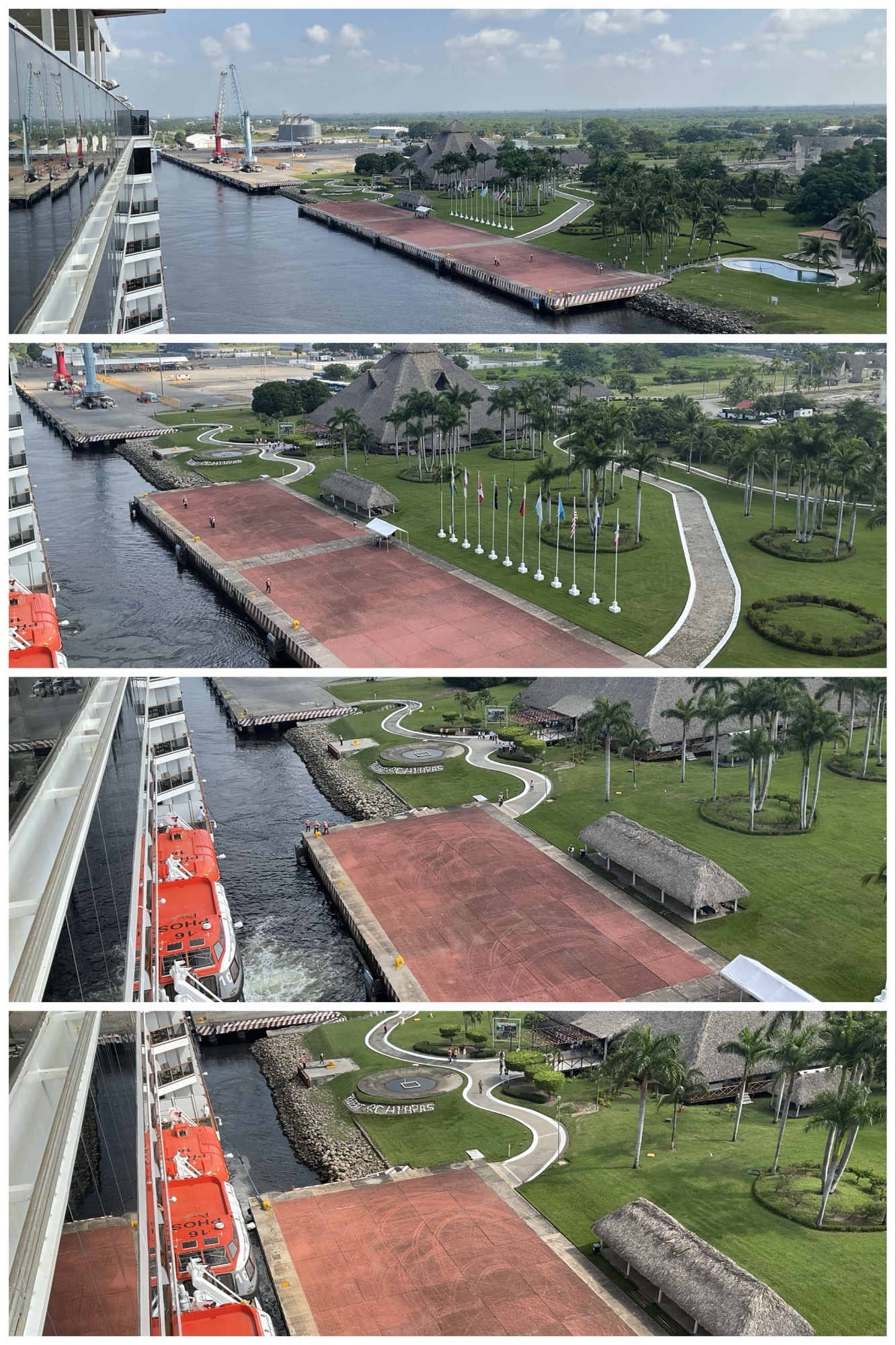

It’s always interesting to watch our huge floating hotel slowly sidle up to a dock that’s parallel to it. It’s one thing for a river boat to move “sideways” – quite another for an ocean ship. On the other hand, a couple of days ago the captain slowly spun the ship in place 180° so that we could back into a docking spot, so I really shouldn’t have been surprised.

We’re docked here from 10 a.m. until 8 p.m., with lots of time to explore. At the cruise terminal itself, there are two huge palapas, many shops, some wi-fi pubs, and a large swimming pool, plus our Canadian flag flying proudly among the other nations “officially” welcomed here!

Right or wrong, we’d been forewarned that walking around the town beyond the port on our own was less safe than we’re used to expecting in Mexico. The city of Tapachula is apparently the entry point for thousands of immigrants who are attempting to make their way north to the U.S.

So, after some initial waffling, we booked an excursion called “Izapa Ruins & Chocolate Discovery”.

The tour description read: journey approximately 45 minutes aboard an air-conditioned bus to the ancient ruins of Izapa. From its beginnings as a small village around 1500 BC, Izapa grew into the region’s foremost producer of highly valued cacao. Many believe it is the site of the origin of the sacred Mayan Calendar, although much study remains to be done to unlock these secrets. Next travel by coach to Tuxtla Chico, where a demonstration in the central plaza shows how the cacao beans are transformed into chocolate. Sample the locally made chocolate and see a variety of regional handicrafts. Dancers put on a lively performance. After a stop at the town’s historic church, you will head back to the pier.

So… history, music, and chocolate. The perfect combination.

ASIDE: We felt 100% safe. There was absolutely no sign of the city being overrun by Guatemalans. In fact, after learning that the state of Chiapas had actually been part of Guatemala before being wooed away by Mexico (who wanted their natural and agricultural resources), we also learned that the border between the two countries is virtually open for back-and-forth travel anyone living within 30 km/18 miles of it.

Much like the Canada/US border, there’s a trend toward cross-border shopping. Currently, every Guatemalan quetzal is worth two Mexican pesos, so most of the travel flows north to shop for relatively cheap food, gas, and retail goods. Tapachula boasts a huge Sams Club warehouse.

Those aforementioned natural resources? Enough water that the dams in Chiapas provide 55% of all of Mexico’s hydroelectric power. Enough arable flat land for cattle, mangoes, corn, and so many banana plantations that Chiquita has two of its own huge branded cranes in the port for the weekly freighter load that leaves here for the US and Canada.

Tapachula and its suburbs are very multicultural, having benefitted over the last 150 years by Japanese, Chinese, and German immigration. Our guide joked that the regional cuisine is Chinese food, since their Chinese restaurants are so good. He wasn’t joking about the impact that the Germans who immigrated in the late 19th century had though. In 1890, Mexican President Porfirio Díaz and German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck collaborated to bring 450 German families to the Mexican state of Chiapas where they settled in the town of Soconusco (about 90 minutes north of Tapachula) to develop the region’s agriculture industry. They brought the expertise needed to develop agriculture in the mountains, effectively creating Chiapas’ now famous coffee industry.

We had a fairly large group today, 41 people, but we had a new air-conditioned full-size coach in which to travel, and an excellent guide in David, a high school teacher of English and Business, who also has a Tourism certificate and teaches Tourism at the local university. He’s a man of many talents! In fact, he should have been teaching today, but by paying for his own substitute teacher was given permission for a day off. It’s a testament to the importance Chiapas is placing on increasing tourism. This year only 13 cruise ships docked here. The state government would certainly like to see more, not just for the economic benefits (despite all those resources that get exported, Chiapas remains one of Mexico’s poorest states) but also, as David explained, to broaden the horizons of the young people here who have limited opportunities to travel. The bonus of the lack of over-tourism – for us – is that the experience here is very genuine, and the people we met very authentic. There’s no sign of cookie-cutter experiences or crass commercialism. Yet.

David was a very engaging guide, sharing lots of information about the things we could see from our coach windows as we headed to Izapa.

He pointed out the fields of corn, which look quote different to what we’re used to because two crops – an old and a new – are harvested simultaneously. When the first planting reaches maturity, the corn stalks are hacked with machetes so that the cobs droop. That downward facing orientation protects them from absorbing more rain. The second planting is then done, by hand, in between the dry stalks. When that second planting matures, both crops are harvested at the same time, for a double yield. In this climate, that means that four plantings can happen each year, with only two expensive harvesting processes needed. All those dry plants? They’re perfect for wrapping tamales!

The Izapa ruins are not on a government-owned or protected site, so it is amazing that they are as intact as they are, although many thousands of artifacts have undoubtedly made their way into local folks’ homes as they cleared farmland. There is an excellent detailed description of the site at Izapa. Lonely Planet describes the site as the “small and peaceful pre-Hispanic ruins” of a city that …was “an important ‘bridge’ between the Olmecs and the Maya.”

Archeologists have theorized that Izapa may have been settled as early as 1500 BCE, making it as old as the oldest confirmed Olmec sites of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlánand La Venta. Izapa remained occupied through until approximately 1200 CE.

What was really interesting was learning about the theory that when the Olmec arrived here, indigenous people already lived here, but that instead of ousting them the Olmec intermarried and traded knowledge with them, giving rise to what we know as the Maya culture.

Izapa was the template for the great Mayan cities that followed. The theory is that it was here that the very stratified Maya class structure was perfected, the language created, the shape of buildings and cities designed. We learned that the “stepped” pyramids were used to reinforce the class structure; when gatherings were held, the highest classes stood or sat on the highest levels, and each level closer to, the ground held a lower class, with slaves relegated to the ground at the very base.

We saw evidence of altars that would have held offerings to the gods, and may also have been used for sacrifices.

We saw the remains of a stone aqueduct system.

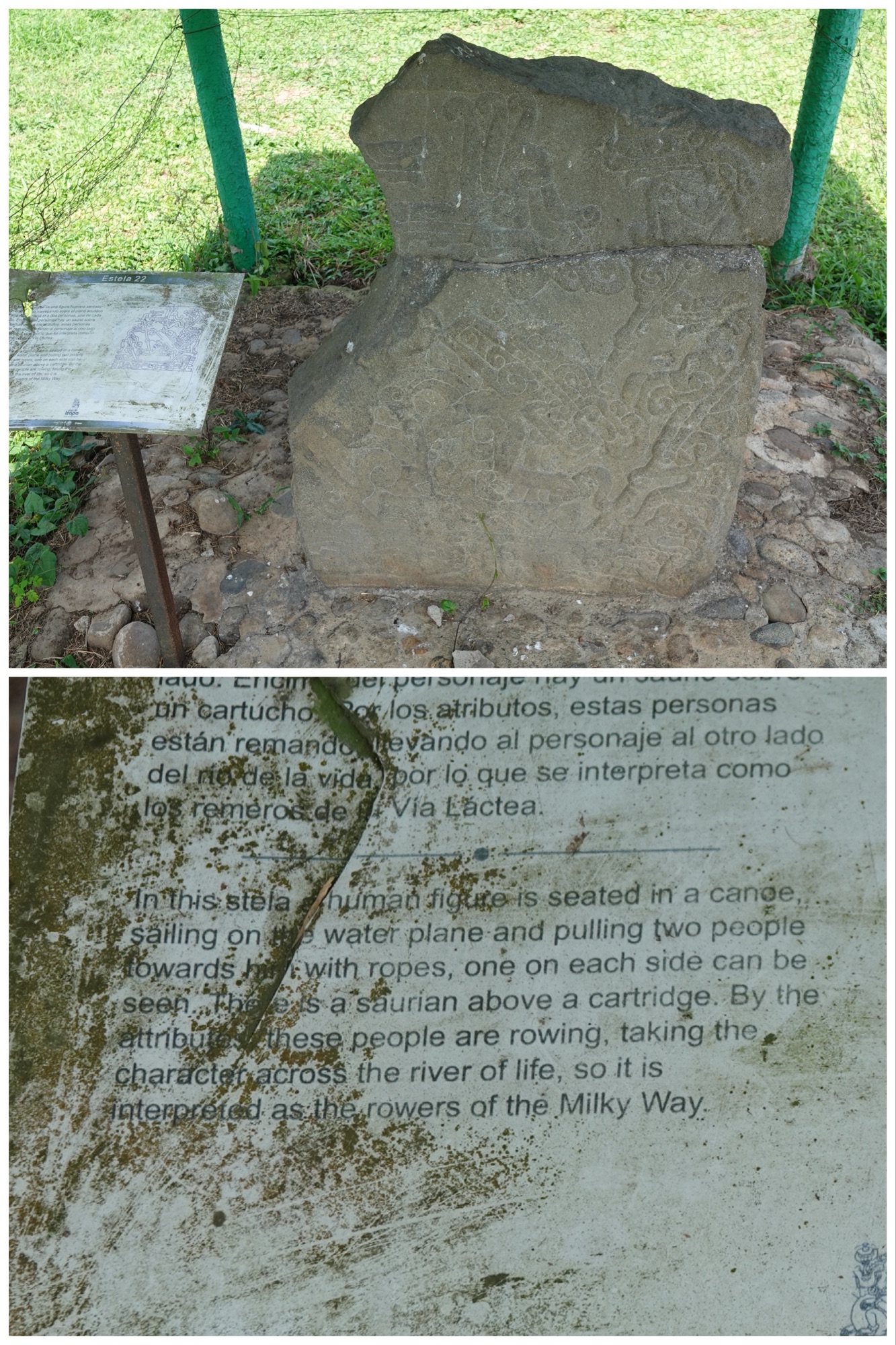

We saw carved stele…

… and the remains of a statue showing a prone worshipper, facing in the direction of the nearby volcano, revered as a god. You can see the soles of the feet and the statue’s backside.

After an hour at the ruins, we re-boarded the coach to head for the small town of Tuxtla Chico (small rabbit, using the local indigenous word for rabbit), famous as being the “birthplace” of chocolate. Almost 4000 years ago, the Olmec were the first to turn the cacao plant into chocolate. This tiny town is apparently where the Spaniards first encountered the paste made from the seeds of the cacao tree, and took it back to Europe with them.

We took a short stroll through the centre of a town which years ago turned down the opportunity for the infrastructure improvements that eventually enabled Tapachula to become the area’s economic centre. It has retained the small-town feel and identity that its residents wanted.

Our first stop was at the brightly painted Templo de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (Church of our Lady of the Candelaria). The Virgin in this church is celebrated on February 2nd each year with a procession in which her statue is carried through the town. This happens in many places in Mexico, but what makes it unique here is the “carpet” on which the procession takes place. In a tradition borrowed from Guatemala, the entire procession route is covered with dyed wood shavings and flower petals, arranged in intricate designs. This “carpet” takes up to 24 hours of hundreds of pairs of hands working round the clock to create, and is gone in the 3-6 hours it takes for the procession to pass.

Our guide explained that this area has no great stones, or gems, or gold with which to decorate a church, but that wood is their most prized building material. That makes the carved wooden doors and ceiling significant.

Even the icons are carved from wood, not stone.

Next we were treated to a display of traditional Chiapan dance, before moving on to the demonstration of chocolate making.

In the town square was a cacao tree in the very early stages of fruit. Each of those small white pips could theoretically become a fruit, but in fact only about 20% of them will.

There are 2 kinds of cacao fruit, the larger original kind, and the smaller more recently developed one.

Both can be broken open to reveal cacao beans coated in a whitish “slime”. That is usually washed off before the beans get dried, but it’s not essential to do so. It’s up to the chocolate maker’s preference. We got to try sucking it off – it had an interesting citrusy taste.

We also got to try lightly fermented cacao juice, which tasted a lot like guayabana fruit – a mix of strawberry and pineapple that is nothing like chocolate!

Once the beans have been de-slimed (or not) they are dried for several days, regularly shaken and turned.

Next the dried beans get roasted. At that point the cacao bean’s skin can be rubbed off. This is when they’re ready to be sold in bulk to big companies like Hershey or Lindt. The current price is around $14USD per kilogram.

Not all beans are sold. Every household in Tuxtla Chico has their own recipe for making chocolate, but all start with grinding the roasted beans – by hand – using the same kind of curved stone mortar and stone pestle combination (a metate) that Ted and I saw Mayan women in the Yucatan use to crush achiote seeds.

Once crushed to a coarse powder, the cocoa – and any special ingredients like cinnamon or vanilla – is shaped by hand into a large ball. It is the oils and heat from the women’s hands that make the cocoa hold together and become a paste.

The ball is then shaped – again by hand – into a log that can be sliced into the traditional disc shapes. Those are used for hot drinking chocolate and baking, but can also be cut up and simply eaten. Divine.

Oh, and the chocolate makers are always women. The men’s jobs are tree planting and fruit harvesting.

It was another humid 33°C/92°F day, with a 50% chance of rain this time (we saw none yesterday), so we covered up against the hot sun instead of sweating our sunscreen off every 30 seconds. As we were leaving the chocolate demonstration, the skies opened with the kind of sudden downpour that we remember so well from Mérida.

Half an hour later, it was back to bright sunshine, rivers of water running along the sides of the streets, and a welcome break from the humidity.

It was a wonderful day, and I’m glad we decided to take an excursion.

Tomorrow, another last-minute excursion decision: a coffee plantation and tour of historic Antigua, Guatemala. The prediction os – again – for rain. Fingers crossed we don’t see it, since I didn’t pack any rain gear this trip. Sigh.

How much walking on this tour?

LikeLike

Not a ton of walking required – we always add as much walking as we can on every excursion

LikeLike

Fascinating — I’ve seen chocolate being made from the beans they’ll sell on, but never the very first stage. Really appreciate your details!

LikeLiked by 1 person