Wandering just slightly off the main pathways between the museums in Balboa Park can reveal some wonderful spaces.

Yesterday we chose to take the path leading to the wood and steel Botanical Building, which is undergoing a multi-year restoration.

There’s a large lily pond/lagoon in front of the building that is home to several turtles, and bathtub to a few ducks and the occasional seagull…

… plus it offers a stunning view looking back at the Casa Del Prado.

En route to the Botanical Building, we’d taken a shortcut past the Old Globe Theatre, where Edith Wharton’s Age of Innocence is currently playing. The original theatre was built for the 1935 expo, but destroyed by arson in 1978. The current theatre is a reconstruction completed in 1981.

There was no matinee, so the theatre wasn’t open, but from its courtyard we had an unexpectedly wonderful view of the domes on the Museum of Us. We’d been so focussed on the tower and the museum’s ornate façade, that we’d never walked around the back!

On the other side of the courtyard was a relief carving of Shakespeare writing on a globe, but what really caught my eye were the two benches located in the shady corner.

The bench in the centre at first glance looks like the more interesting one, but the lower bench’s dedication made it the one I’ll remember.

In memory of Globe docents Ruth and Irving Belenzon.

Children will look to you

for which way to turn

to learn what to be

careful before you say “Listen to me”

children will listen.

- Stephen Sondheim, “Into the Woods”

Isn’t that the best quote you can imagine for a docent?

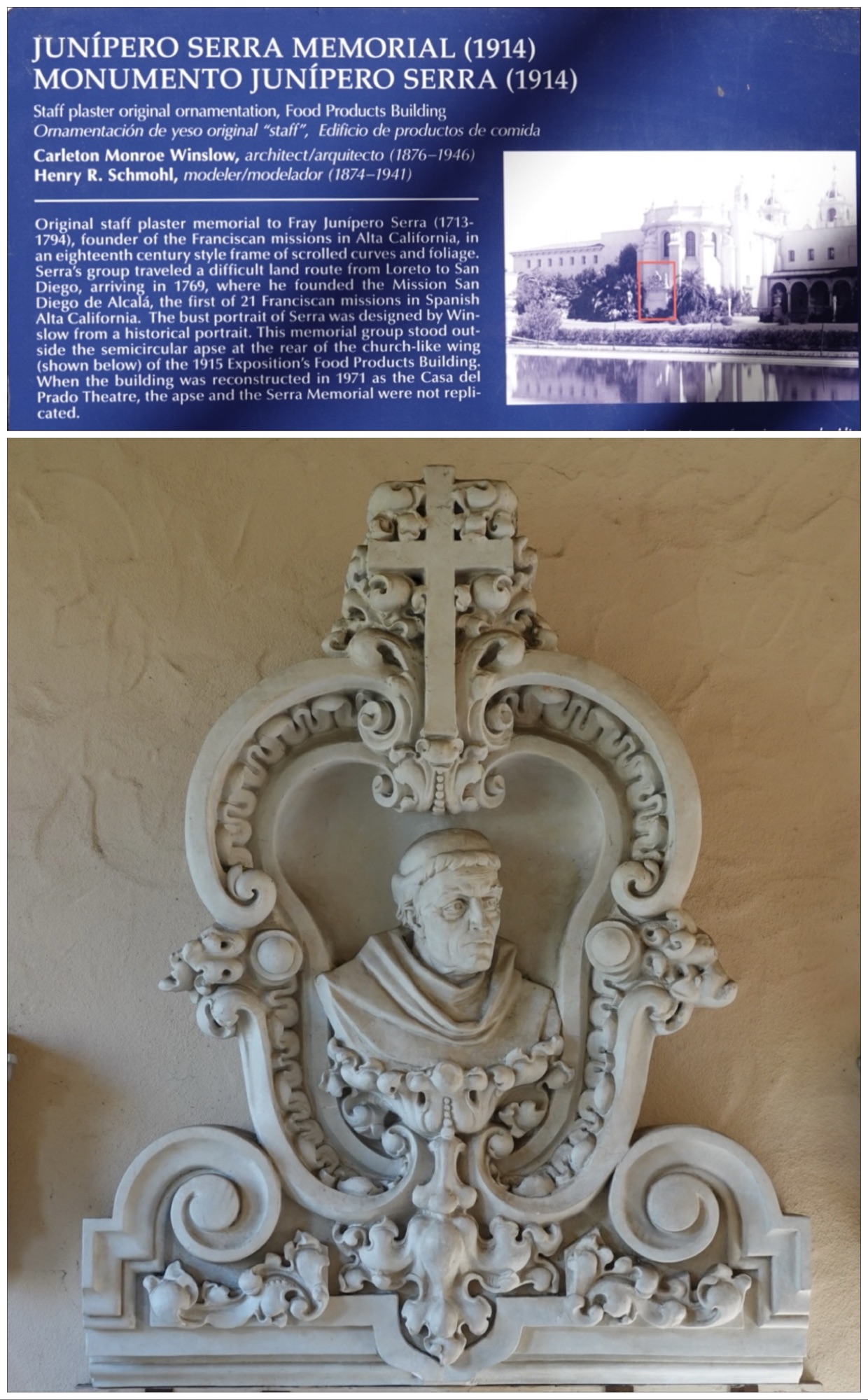

Planning to head back to the main road, my eye was caught by what looked like a sculpture in one of the inner courtyards of the Casa Del Prado. The area otherwise seemed as if it belonged to the administrative offices, but it was clearly a way to shortcut back to the road, so…

What had caught my eye was a portion of the Angel Head finial (above) from the San Diego History Center. This replica was cast for the 1971 reconstruction of the building now known as Casa del Prado. The finial matches the top section of the larger original piece. The plaque beside it explained that this replica was not used on the reconstructed building, perhaps because of its chipped base.

But while it was a replica that caught my eye, there were original pieces here too! We’d stumbled onto the Panama-California Sculpture Court, created in 1974 by the City of San Diego and The Committee of One Hundred.

After being used as models for the exterior of the reconstruction, the original pieces, and some pieces of concrete that remained unused, were taken to the Chollas landfill where scavengers began to take the pieces as souvenirs. Hundreds must be decorating San Diego gardens today, although an art school also managed to save a few as examples of early 20th century San Diego architecture. Seventeen pieces were eventually returned to this courtyard in 1974 to create the Sculpture Yard.

Most of the sculptures exhibited here were outside the “temporary” 1915 Panama-California exhibition building that was previously on this site, and reconstructed in 1972, but there were also a few others saved.

The models of the three Spanish painters (below) were integrated into the exhibition in the following year.

The sculpture yard offers visitors the ability to get close the sculptures, observe them and touch the details made by the artisans.

As we continued to wander around the park, we came across the Indian Head pilaster in situ!

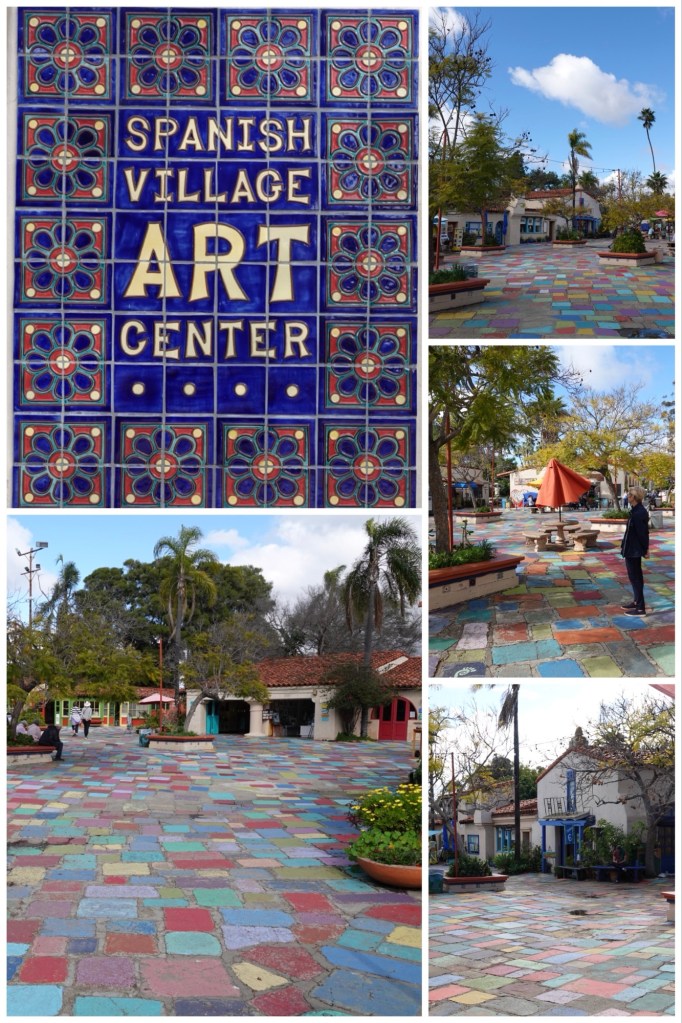

We’d intended to check out the Balboa Park carousel, which unfortunately wasn’t open, but on the way there we “found” the Spanish Village Art Center, a collection of 29 working artist studios housed in an early 20th-century depiction of an old village in Spain.

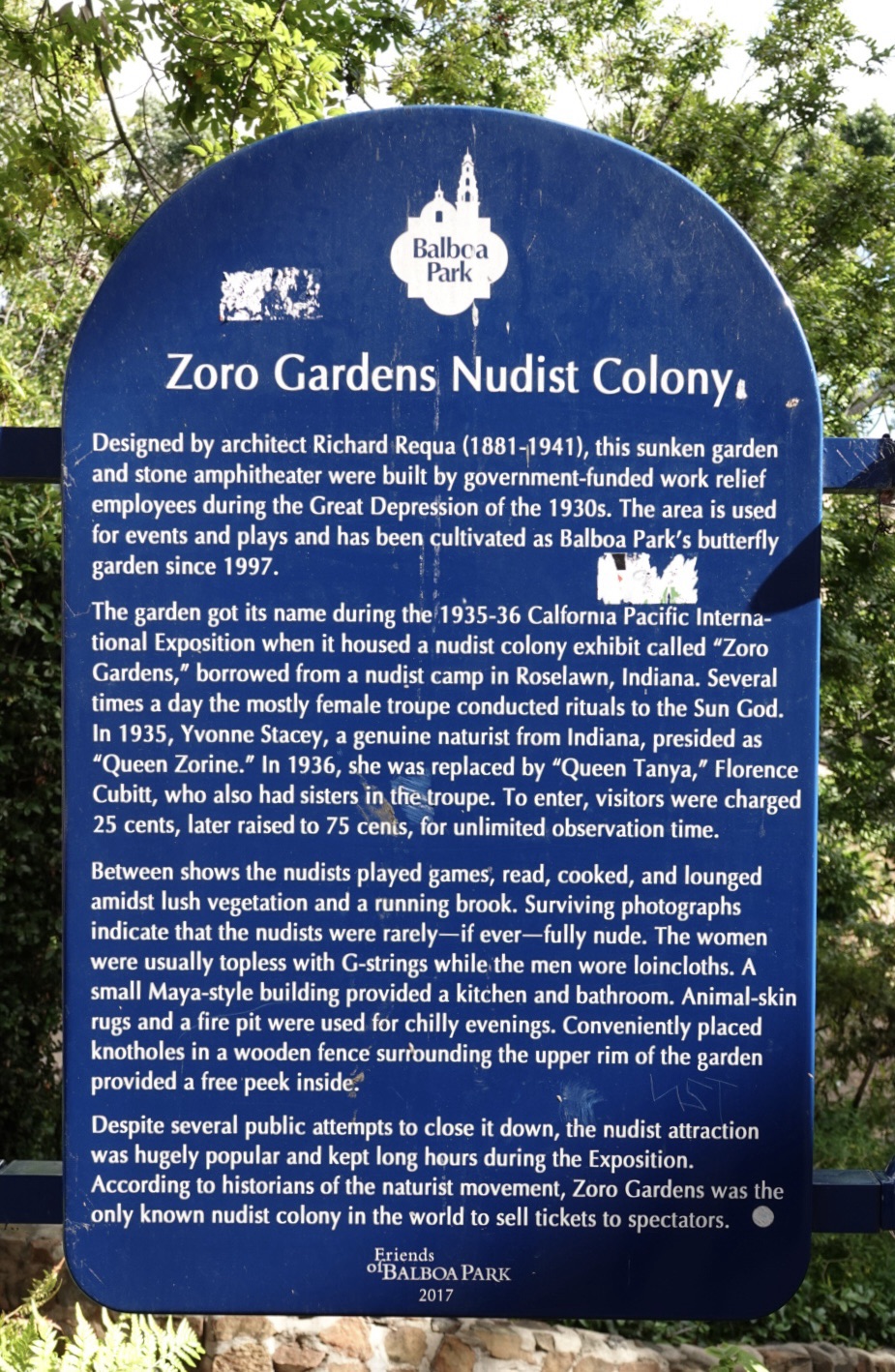

We detoured behind the Casa De Balboa on our way out of the park, and found one more weirdly intriguing spot hiding in plain site:

The “garden” looks deceptively boring, until you read the sign (below).

The 1935 expo must have been quite eye-opening … in ways we would never, ever have expected.

Hiding in plain sight indeed.

You bring everything to life!!

<

div dir=”ltr”>As a parting gift, you should consider sending a coup

LikeLike

Weird and wonderful! Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person