It was a gorgeous sunny day, perfect for heading out of Adelaide proper and into one of the oldest towns in South Australia: Hahndorf.

Almost our first stop in this little heritage German town was its art gallery and history museum. I wanted to know why a community of Germans ended up in Australia early in the 19th century.

Inside the entrance to the museum was a model of a zebra. We were confused, although that would not be the case for long.

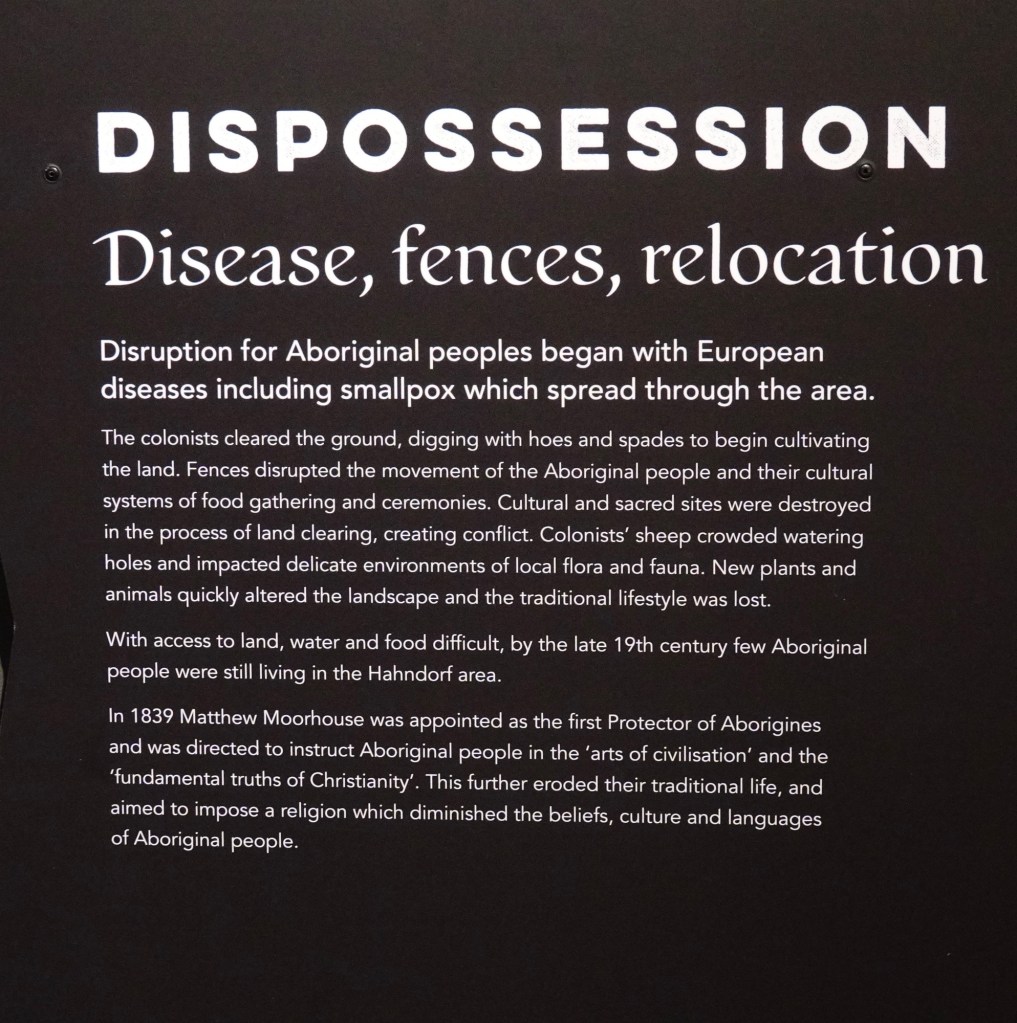

The museum reminded us that Australia has one of the oldest Aboriginal cultures in the world, going back 50-60,000 years, but its written history dates only to Dutch exploration in the 17th century. After that, we all know the history of Australia being used as a penal colony for Britain beginning with New South Wales in 1788.

It didn’t take long before non-penal colonies were seen as a good thing: South Australia (the state we’re in now) in 1836, and Victoria (the home of Melbourne, where we’ll be next week) in 1851, were founded as free colonies; they never accepted transported convicts. As such, they needed voluntary migrants as labour to support the colony’s development.

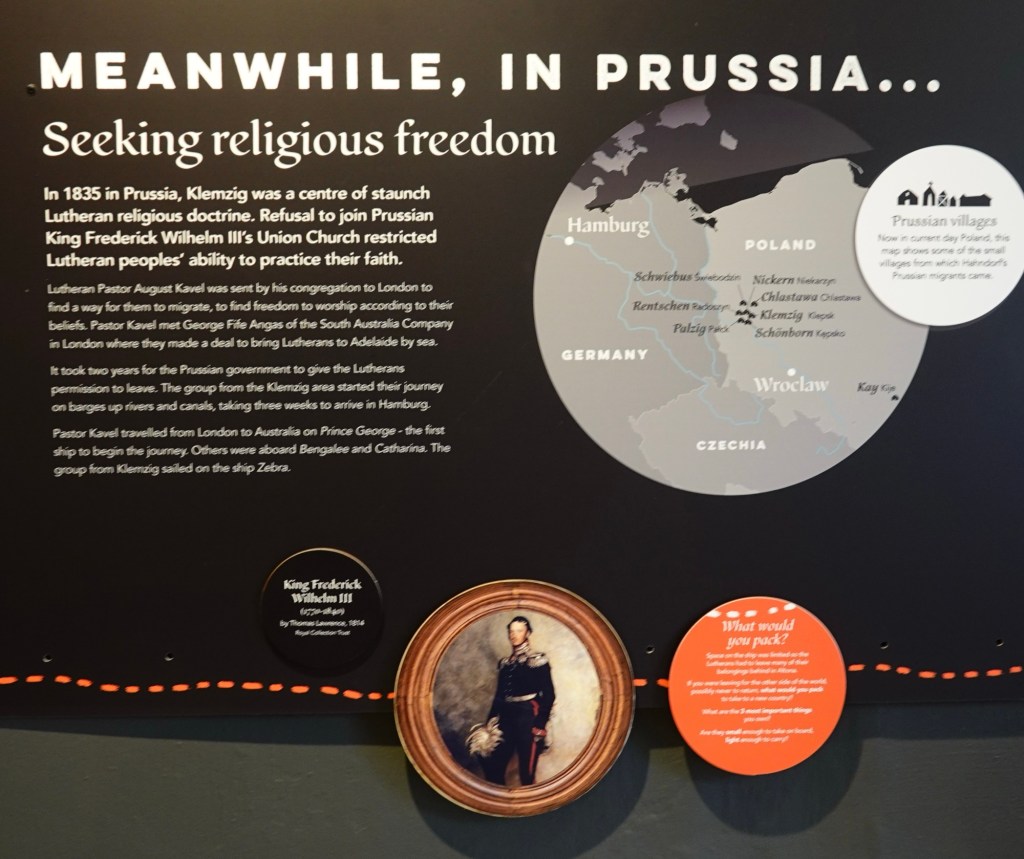

In Hahndorf’s small history museum, the poster explaining how this town’s founding was related to that need had the tagline: “Meanwhile, in Prussia…”

I was fascinated by the story of why 54 Prussian families left what is now Poland to have the freedom to practise their Evangelical Lutheran religion, because my Dad’s family came from the same general region and were also Evangelical Lutherans, as was their large extended family. Why didn’t they feel the need to emigrate? I’ll probably never know.

Perhaps simply worshipping without enough fanfare to attract the Kaiser’s attention was enough for them.

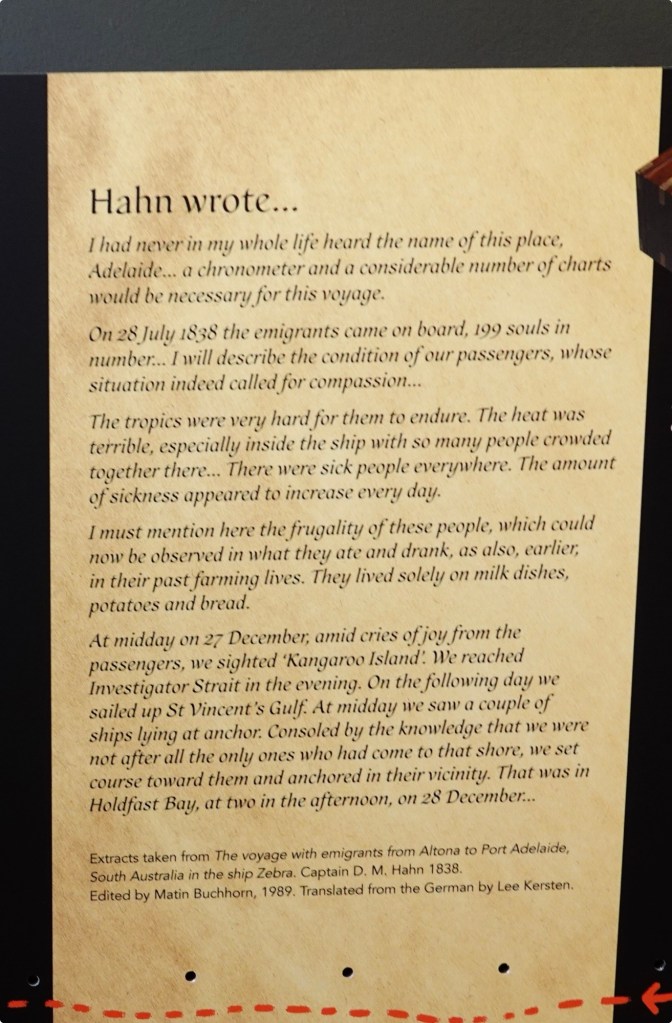

The 54 families, 199 people, fled Prussia by travelling along a river canal network to Altona and by August 12, 1838 left the port of Hamburg aboard the ship Zebra (!) under the command of Danish Captain Dirk Meinerts Hahn. Hahn, who had never before sailed to Australia, completed the voyage in 20 weeks.

Signs in the museum explained that sea sickness, scurvy, typhus and storms plagued the ship’s long journey. The passengers were encouraged to eat sauerkraut and raw potatoes to stave off scurvy. I wonder if that’s why Germans are called “krauts” but Brits are called “limeys”. Given the length of the voyage and rough sea conditions, it’s almost surprising that only six adults and five children died during Zebra’s voyage.

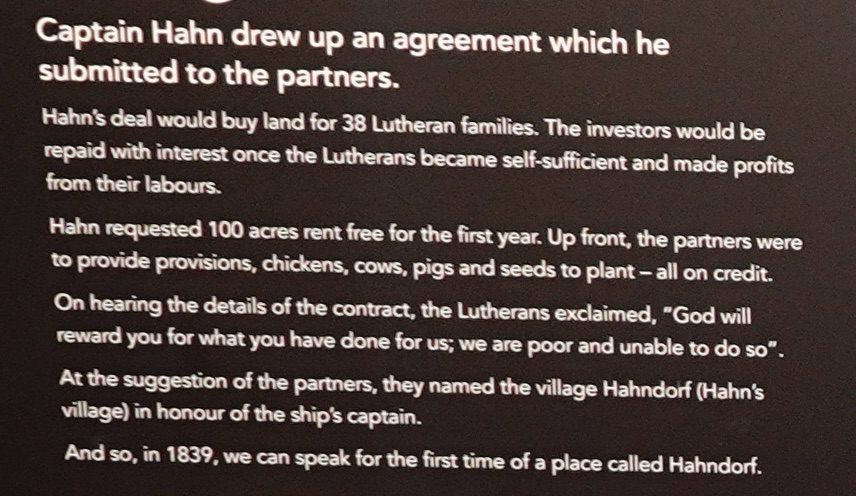

Fertile land around Mount Barker was being sold by the colonial Government to investors who apparently saw the Zebra’s passengers as a useful supply of experienced farm labour and tradespeople. Unfortunately, while the immigrants were skilled farmers, they had little money to buy land. The story of Hahndorf is in many ways the story of a Danish Captain who believed in his passengers enough to back them.

Adelaide was founded at the same time as its state: 1836. Tiny Hahndorf was established just three years later in 1839.

The area that was sold to the Danish ship captain who brought the community here was, of course, originally Aboriginal land, but we learned that few of those original inhabitants remained. As one community put down new roots, another was uprooted.

There were stories of both individual and community contributions toward making Hahndorf a thriving village, but it took less than four generations (about 80 years) for the residents of Hahndorf to feel the pressure of not being wanted again.

The museum’s narrative read: “Britain declared war on Germany in 1914. As a dominion of the British Empire, Australia was automatically at war.

Walking around Hahndorf at that time, you would hear people speaking German. The majority of locals had German names. Hahndorf’s pub was called The German Arms. This all spelled danger.

The war years of 1914-1918 subdued German cultural traditions. Many German families changed their names to be English sounding. Anti-German feeling was intense and the Prussian migrants felt the kind of persecution their ancestors had settled in Hahndorf to escape. In South Australia 69 towns with German names were changed to English names. Under the War Precautions Act 1914, suspected enemies could be arrested and interned at the slightest excuse. Every state had internment camps with South Australia’s on Torrens Island. The camp was only eight kilometres up-river from Port Adelaide – where the migrants had first landed.

Lutheran schools were closed by an Act of South Australian Parliament in 1917.”

In 1914, the town’s name (along with 68 other “German” named towns) was changed to Ambleside, but the name Hahndorf was restored in 1935 in recognition of the settlers’ contributions to the establishment of South Australia, and remained unchanged despite WWII.

During World War I, The German Arms hotel was raided by police and the army, searching for weapons. They must have taken the name literally – they found nothing. Later, acting on a tip off, they returned to the hotel, this time certain there was a hidden radio transmitter. Again, they found nothing. We ate lunch there today; there are still no weapons or radio transmitters.

In 1916 the owners changed the name of the pub to The Hahndorf Hotel. Then, to avoid any German association, Hahndorf itself was renamed Ambleside. So the pub was renamed again – to become The Ambleside Hotel. It wasn’t until 1976 that the hotel once again became The German Arms.

In 1988 Hahndorf was declared a State Heritage area as the oldest German settlement in Australia. Entrepreneurs saw opportunities to benefit from Handorf’s German heritage and new shops and businesses appeared. “Fitting a German stereotype, many adopted a cheerful Bavarian character unlike the original more austere Prussian identity.”

I’m not sure if I should be offended by that comment from the museum’s documentation. I think instead I’ll try to channel the humour of the museum curator who captioned this 1890 photo of a Prussian settler family:

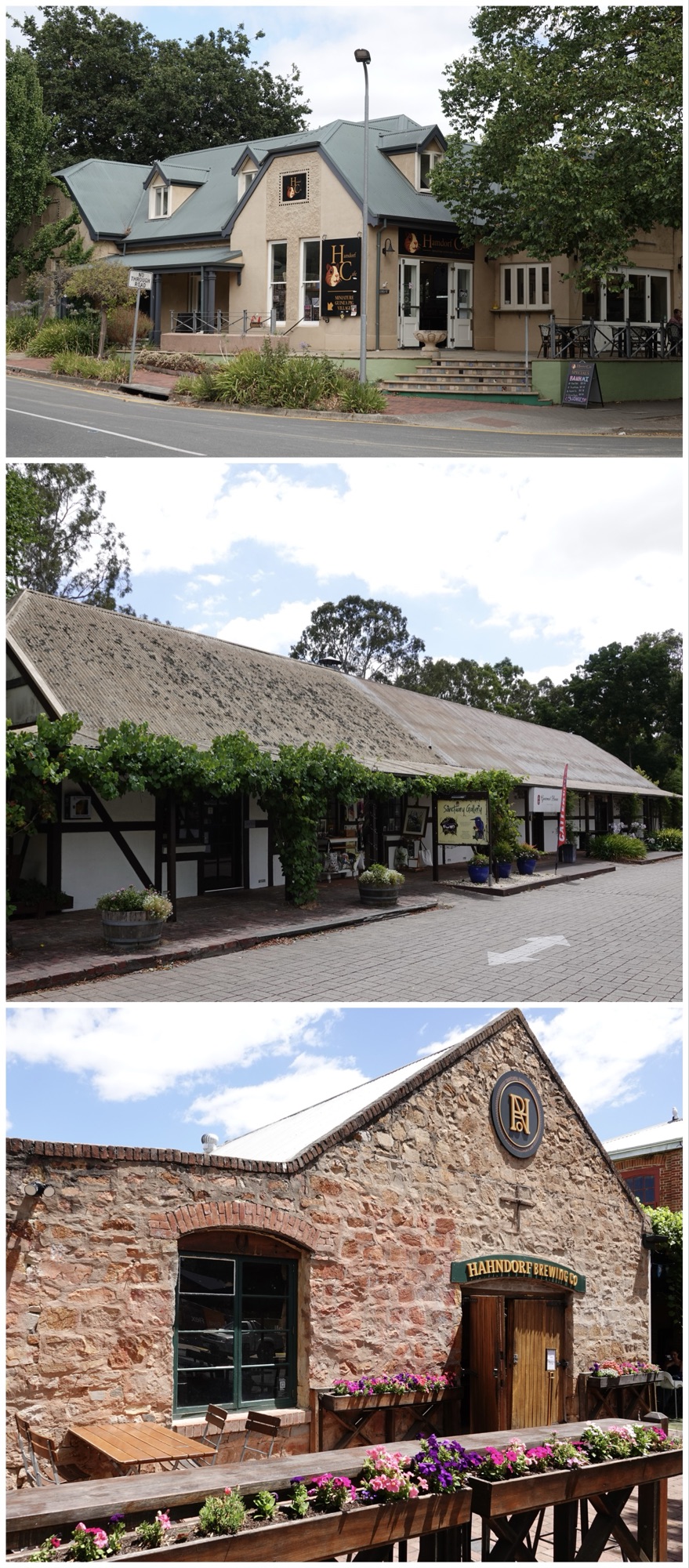

We spent a couple of hours just strolling the main street, stopping for “Kaffee und Kuchen” (cake and coffee), and taking photos of the German-looking architecture. There were even a few buildings constructed in “Fachwerk”, the same brick, wood, and wattle style that is visible everywhere in my cousin’s hometown in Lower Saxony.

As a bonus to our visit, Ted managed to capture photos of several very noisy rainbow lorikeets, which are native to South Australia.

After getting back to Adelaide, we made it to the Botanical Gardens, but that visit merits a separate episode.

I love following along on your travels. Hahndorf reminded me of Kolmanskop, the town in the Namibian desert founded by German diamond miners, because it was a strange place to find German immigrants. Did you go on that excursion?

And you found a women’s resale clothing store! Did you buy anything?

LikeLike

We didn’t go to Kolmanskop, but we did go to Lüderitz. I remember thinking that my German cousins would have been fascinated. And yes….sigh…I’ve now traded the capris and long-sleeved tee that were in my suitcase for a much trendier pair of wide-legged pants and a gorgeous white Italian-made cotton tunic. I could go silly here in Oz if only I had the strength to lug a larger suitcase!

LikeLike

very cool history recap. And those lorikeet pics, wow!

LikeLiked by 1 person

They were irresistible because they were so darned noisy!

LikeLike