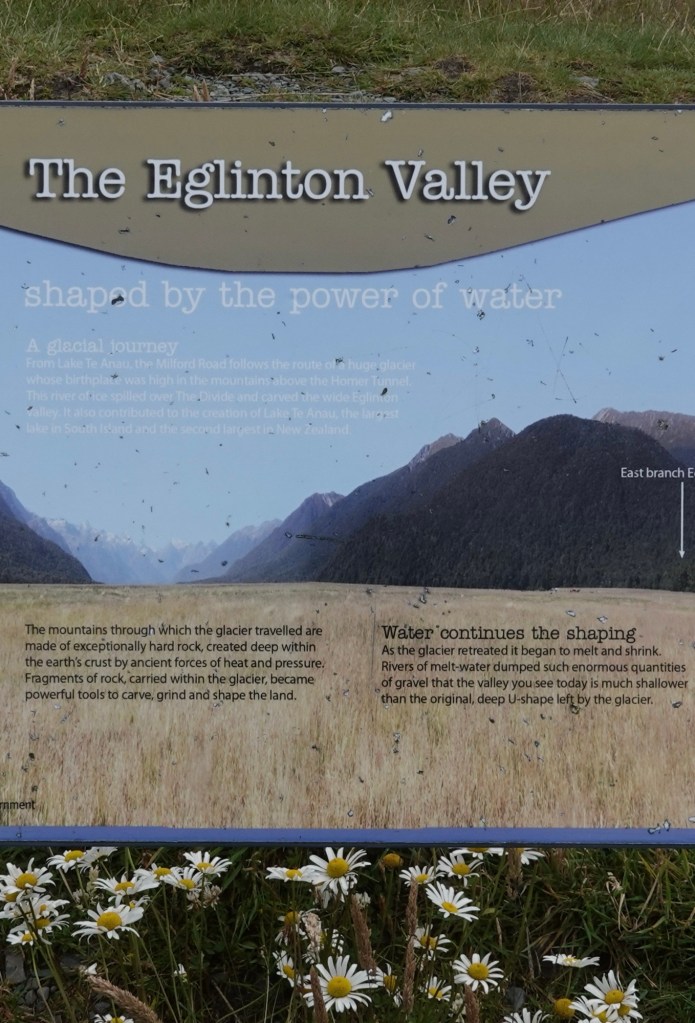

Our destination today was Milford Sound, and getting there involved – no surprise – a coach ride. Along the way, travelling through the Eglinton Valley, we made a couple of photo and leg-stretching stops, and learned more about New Zealand’s geography, flora, and fauna.

We passed by toi grass, which is native – but the very similar pampas grass we saw is invasive, imported from Argentina as an ornamental grass.

We learned that all the gorgeous hydrangeas we see on roadsides are invasive. (There were none on today’s route.)

And then there are the animals. Again.

Rabbits were imported for sport, but with no natural predators and a lush land on which to forage, flourished unchecked. When the number of rabbits became a problem for farmers, weasels, ferrets, and stoats were imported to control them. Predictably, those predators didn’t obediently stay in one place; they escaped to areas without rabbits and instead decimated New Zealand’s flightless bird population.

Ted was reminded of the children’s song There Was An Old Lady Who Swallowed A Fly, in which the old lady ingests ever larger and more bizarre animals in the hope of getting rid of the previous problem. In the end, “There was an old lady who swallowed a horse. She died, of course.” We’re seeing evidence that New Zealand has learned from past mistakes, so that its ecology will not suffer the old lady’s fate.

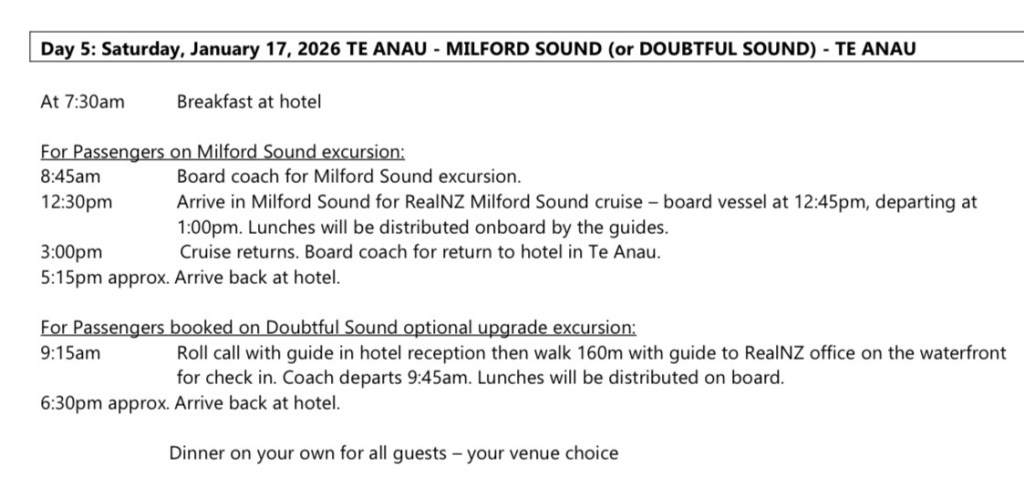

We drove over 3 hours through forests, National Park lands, and uninhabited grasslands.

In Fiordland National Park we stopped at Mirror Lakes, accessed by a picturesque boardwalk.

Today’s conditions were not perfect, since there was a slight breeze rippling the lake surface. Still, we got the idea.

New Zealand’s South Island is huge by global standards—larger than most U.S. states and comparable only to Canada’s mid‑sized provinces. It covers 150,437 km², larger than Nova Scotia , New Brunswick, and PEI together, or in the same size class as places like Georgia + South Carolina combined. BUT, its population is only about 1.24 million (fully 1/3 of which is in Christchurch). By comparison, the three Atlantic provinces have a combined population of 2.1 million, and Georgia and South Carolina’s combined population is 16.66 million. No wonder it seems so devoid of people here, even for those of us used to Canada’s eastern seaboard.

We passed scree fields between the mountains, made of loose “metal”, which is the New Zealand term for gravel or crushed stone. These areas of loose stone are incredibly treacherous.

Still, there were beautiful spots.

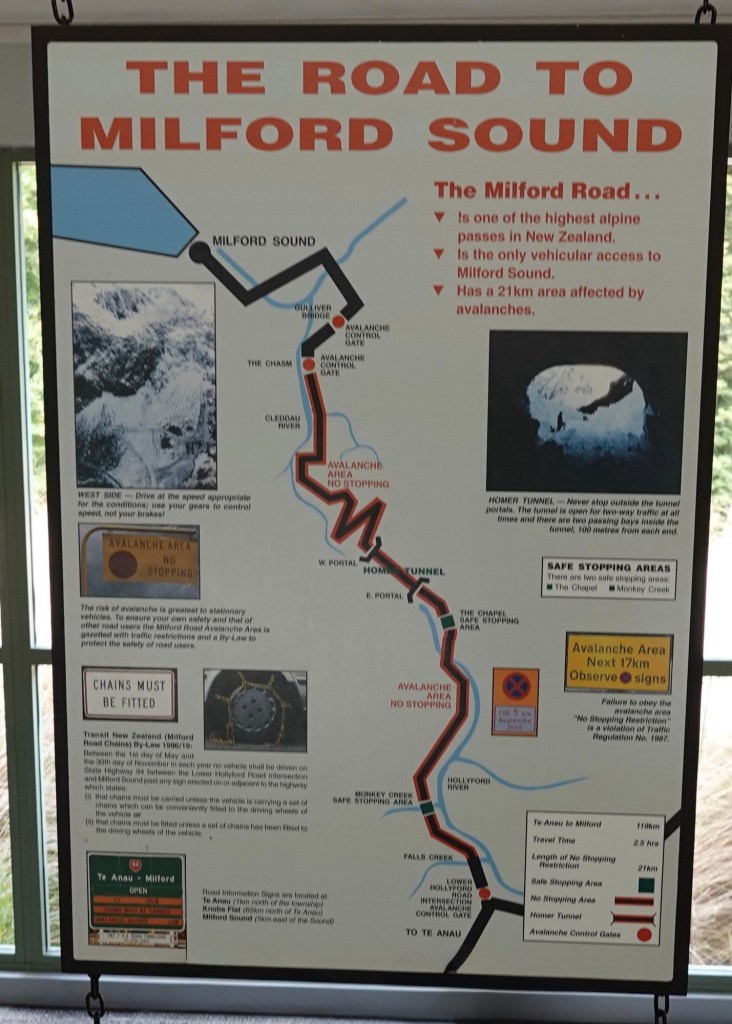

The Milford Avalanche System operates in this area, where there are 85 different avalanche zones, 50 of which can affect the roadway.

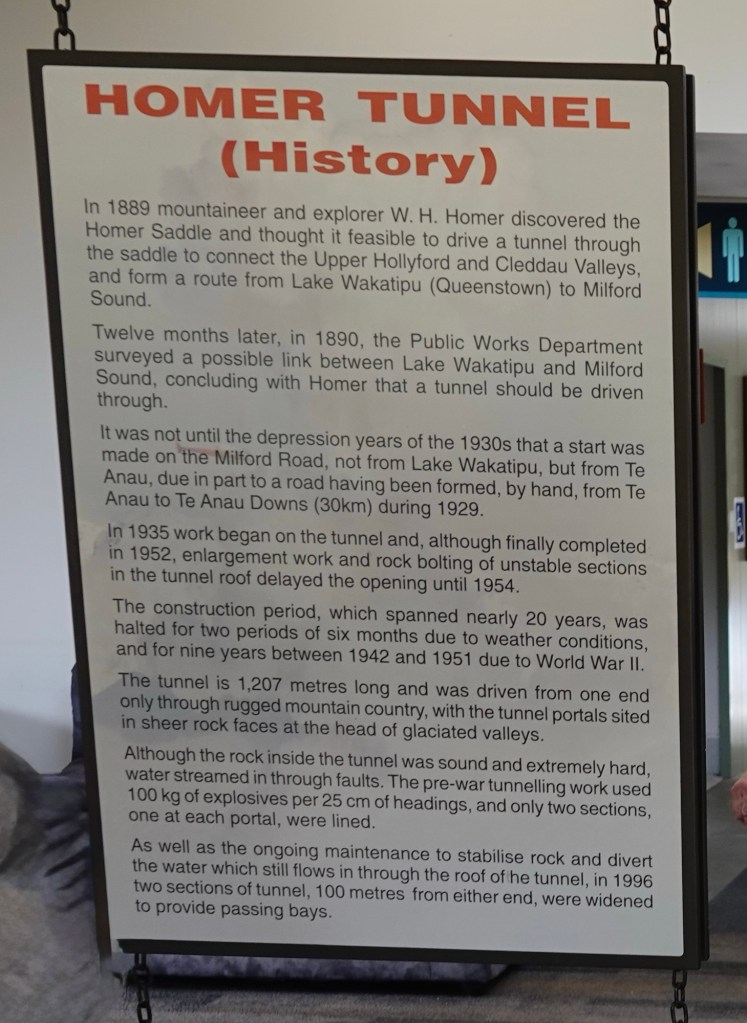

We travelled through the Homer Tunnel, which opened in 1953.

The tunnel is straight, which none of the other roads on which we drove were. It was originally single-lane and gravel-surfaced; its walls are still unlined granite. The east end is at 945m/3100 ftelevation; the tunnel runs a length of 1270m/4166 ft at approximately a 1:10 (dropping 1 metre in depth for every 10 metres travelled horizontally) gradient down to the western end. Until it was sealed and enlarged it was the longest gravel-surfaced tunnel in the world. It was built as a two way road but now, with tour buses and larger vehicles, it has been turned into a single lane tunnel, signal light operated.

Once we emerged, we crossed the Tūtuko River, with its bright glacial waters flowing over huge boulders.

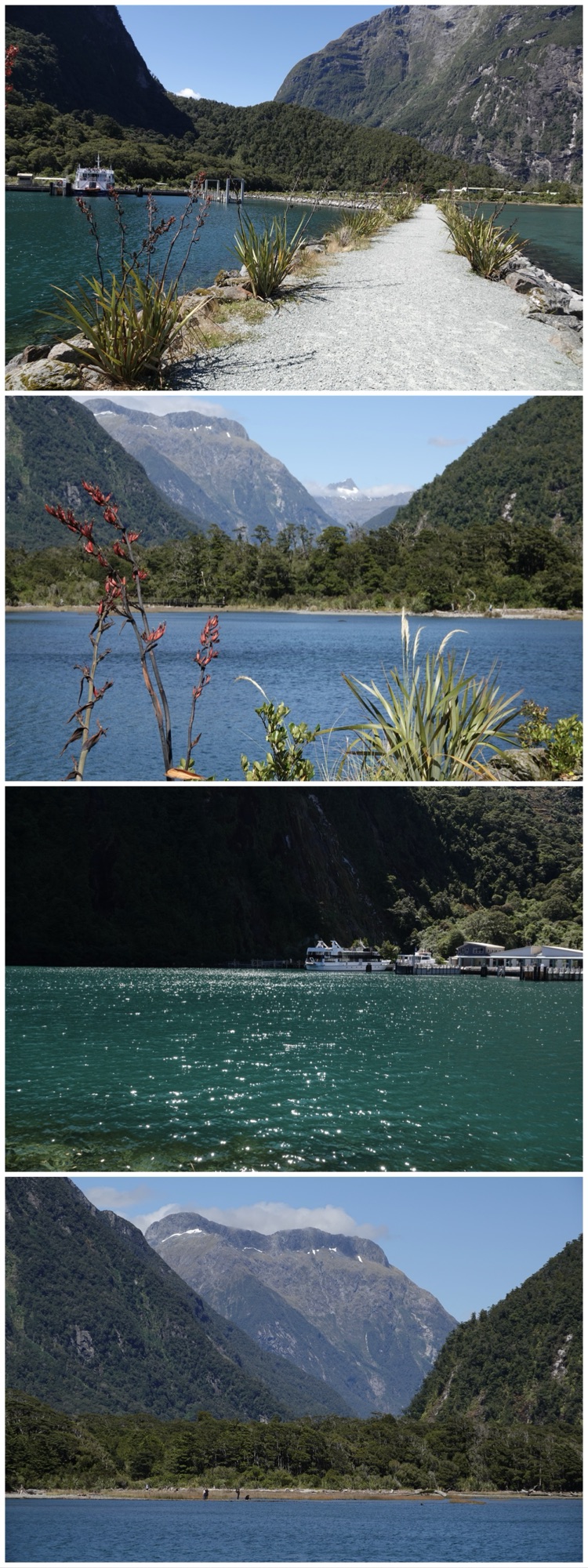

And then we reached the Cruise Terminal at the Sound. There was a map showing our round trip cruise route between Milford Terminal to Anita Bay.

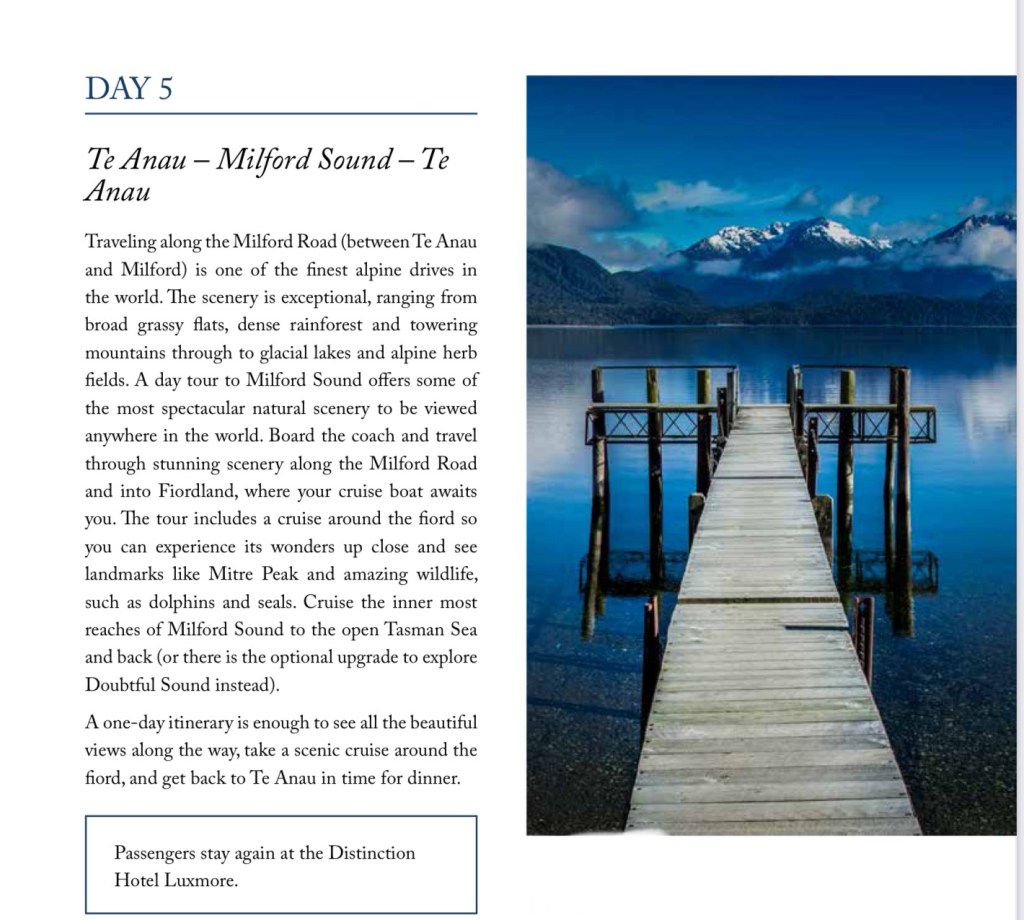

Milford Sound is the northernmost of New Zealand fjords, located in an area called the Fiordlands (spelled here with an “i”).

Even before boarding our boat, the views just walking around the Terminal area were breathtaking.

We really lucked out with bright sunshine and very little wind, given that the Sound is one of the wettest places on earth with up to 7m/23ft of rain falling each year. There is no point in measuring rainfall in millimetres the way most places do. In the flood of 2020 a metre of rain fell in just 24 hours completely flooding the ship terminal here at the sound.

And wind? Wind speeds can reach 120 knots/224 kph/138h.

Off we went.

The Milford Mariner has three huge masts, but its sails were, sadly, furled.

The first waterfalls we saw were Sterling Falls. We’d get a much closer look on the return leg of our cruise.

Although Lady Bowen and Sterling Falls are always visible, the other THOUSANDS of falls and cascades only appear when it rains.

Our ship’s onboard naturalist explained that even though Milford Sound was historically named a sound, its characteristics make it a true fjord: a long, narrow, deep inlet of the (in this case Tasman) sea between high cliffs carved by glaciers. A sound is generally a wider, shallower sea inlet or channel, often formed by a flooded river valley or separating an island from the mainland. The key difference is origin: fjords are glacial, sounds are not.

Our first fur seal, affectionately called “rock slugs” by the Kiwis. When dry, the seals are perfectly camouflaged on the rocks.

They’re much more easily seen when wet.

We saw more seals at Windy Point, which is also where the wind speed measuring station is located that sends data back to the harbour.

Pixie and Faery Falls will be completely dried up unless there is rain in the next 48 hours.

We could get as close as we did to the shore because the sound is about 260m/850ft deep right at the shoreline, a depth approximately equal to the height of the surrounding peaks.

The shallowest part of the fjord at 60m/200ft deep coincides with the Terminal Moraine, the rocky beaches attesting to the fact that this was once where the glaciers ended at the Tasman Sea.

The sea was uncharacteristically calm today – we’ve had incredible luck with the weather!

The naturalist pointed out a beach with yellow stones that contain ponamou, the green stone sacred to the Māori.

On the return trip, our view of the sound was exactly like what Captain Cook would have seen the first time he sailed here looking for a sheltered cove.

Seal Rock, aptly named.

One last look at 163m/535ft tall Sterling Falls, where we got close enough to get “kissed by the mist.which According to Māori legend, that means we’ll wake up tomorrow feeling – and looking – ten years younger. It’s a “glacial facial”!!

The 40m overhang (below) was created by glacial “plucking”, an erosion process where a glacier freezes onto bedrock and “plucks” huge chinks of rock out when it moves.

We were directed to notice the horizontal grooves, called glacial striation, which are evidence that the glacier moved at a rate of about 70m/day.

The vertical grooves on the Cascades Range each represent a waterfall’s path after rain.

The largest mountain bordering the fjord is Mount Pembroke at 2015m/6909 ft tall, home to the remains of the glacier that originally carved out much of this fjord.

The last falls we got close to were Lady Bowen Falls, where the water cascades down 162m/531ft. These falls provide all the fresh water for the ship and the harbour terminal.

And then, all too soon, our cruise was over. It really didn’t seem like 2-1/2 hours had passed.

Our drive back to the hotel necessarily took the same route we’d driven in the morning, but in the reverse direction. I slept.

We had fish and chips in the pub attached to our hotel before calling it an early night.

Tomorrow we’re heading to Dunedin.

Beautiful. Typo? Mt Pembrook’s ht

LikeLike

Thank you! (Voice to text LOL)

LikeLike