We got one last look today at the millennia of history the Egyptian civilization has to share.

Our last excursion of what has been an incredibly enriching trip, was to the NMEC (National Museum of Egyptian Civilization). The museum is quite new, designed in 2006 and opened just 5 years ago. As was the case with the GEM, the Arab Spring in 2011 halted work on the NMEC for almost 3 years. Its official opening took place just before the pandemic hit.

It was purpose built to showcase the mummies of 22 New Kingdom pharoahs, which were formerly poorly displayed in the old Egyptian Museum.

Once the museum was ready, the 22 mummies were moved from the old museum to the NMEC in specially designed vehicles in a ceremonial parade that was broadcast live by the news channels of 54 countries.

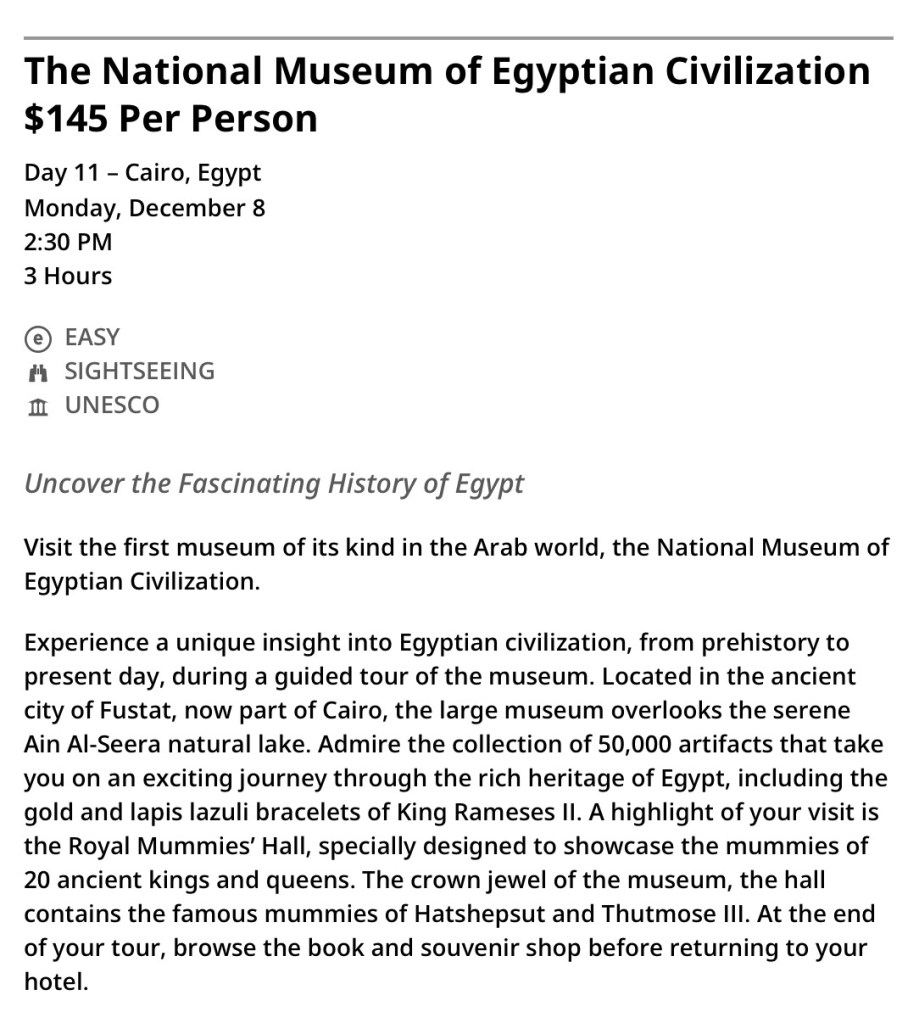

Before we reached the museum, Walid summarized what we’ve learned this week. There was a chart in the museum that verified everything he’d told us (not that we doubted him!), although Walid thoughtfully rounded some of the dates for us to make them easier to remember.

Walid reminded us that around 3000 BCE hieroglyphics first appeared, supplementing pictograms, and that we had seen the oldest hieroglyphics ever discovered when we toured Sakkara!

“Ancient” Egypt officially spanned from 5500 BCE until 332 BCE, broken into various periods, of which the “new” dynastic period lasting from about 1550 BCE – 332BCE was definitely the best documented, and so the most interesting to us. All the tombs in the Valley of the Kings date to this period.

In 332 BCE things changed, first with Alexander the Great’s brief rule, and then the Ptolemaic period that lasted all the way through to the reign of Cleopatra VII, followed by a period of Roman rule until 395 CE.

The Romans overlapped a bit with the Coptic (Egyptian Christian) Byzantine Empire from 330-641 CE.

In 641 CE the Arabs invaded, bringing the Islamic religion, and Egypt became a Muslim country

Today Egypt is still 82% Muslim, 18% Coptic Christian.

On to our tour.

The museum is architecturally stunning when viewed from the exterior courtyard.

Inside are vast open spaces constructed of polished granite, with limestone and sandstone accents, made interesting with wood and gilding.

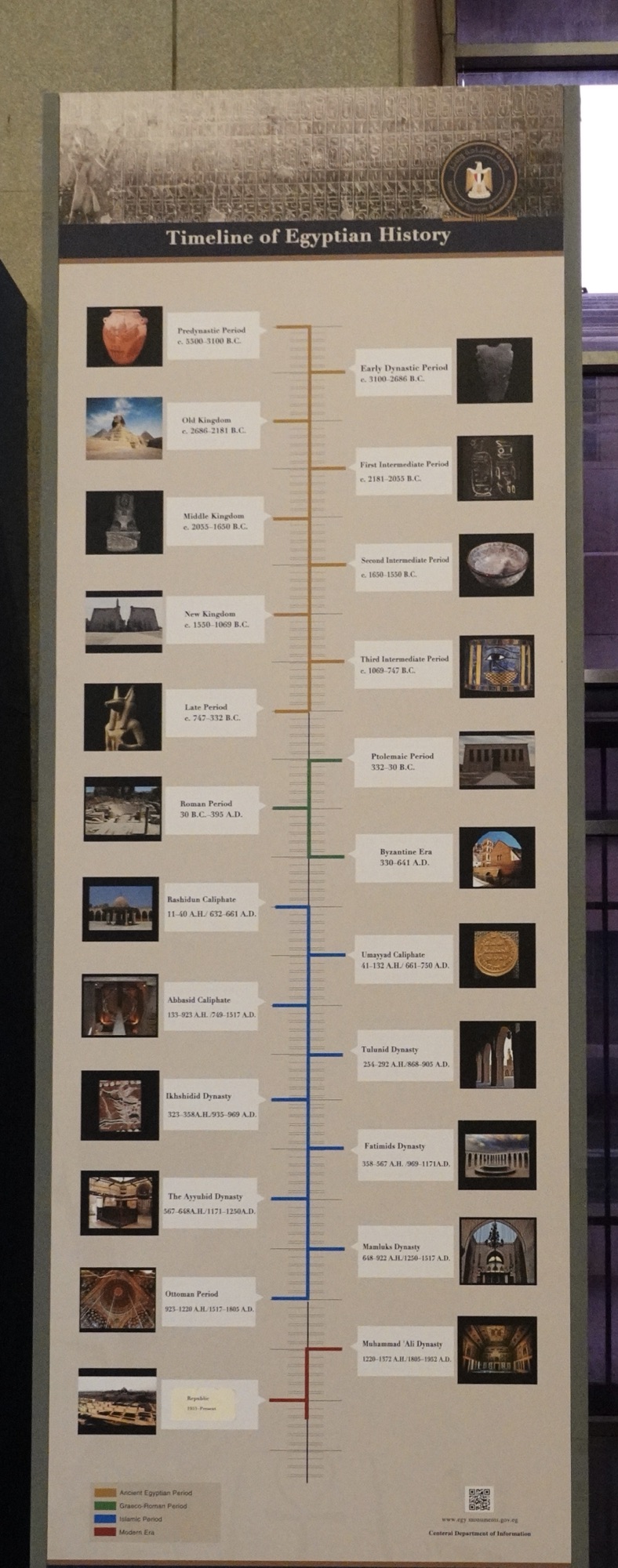

In the centre of the main floor in a huge rotunda below a pyramid shaped ceiling is an area where images are projected onto the floor and around the outside of the circle. Those images include pictures of the mummies, pictures of tombs, pictures of Egyptian archeological sites, and pictures of ancient artefacts.

Walid gave us a tour of the highlights of the artefacts in the museum, and then we were given free time to go and view the mummies on our own since, that is an area of the museum in which talking – and hence guiding – is not allowed.

Proceeding counterclockwise through the exhibit floor took us chronologically from the prehistoric period all the way through to the Ptolemaic era.

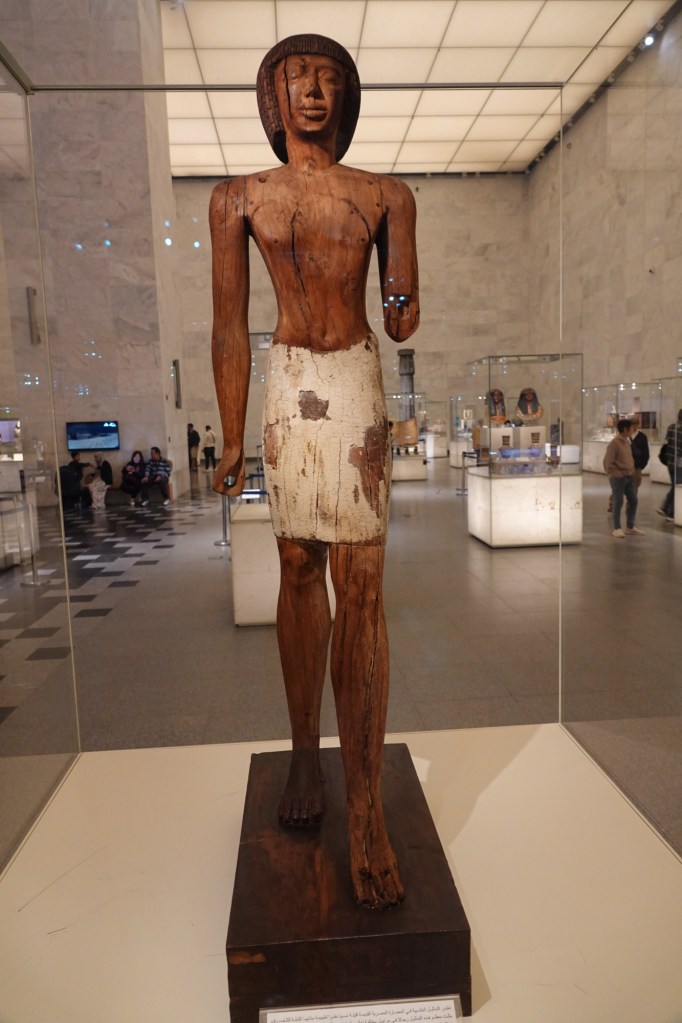

The black granite statue from about 1500BCE is of Sekhmut, the architect who loved Pharoah Hatshepsut and built her what became her mortuary temple. He is depicted as a child on his mother’s lap.

The second statue Walid wanted to tell us about was a basalt carving of Pharoah Thutmoses III, the stepson of Hatshepsut, who reigned for 17 years, during that time defeating the Nubian’s, Syrians, and Hittites.

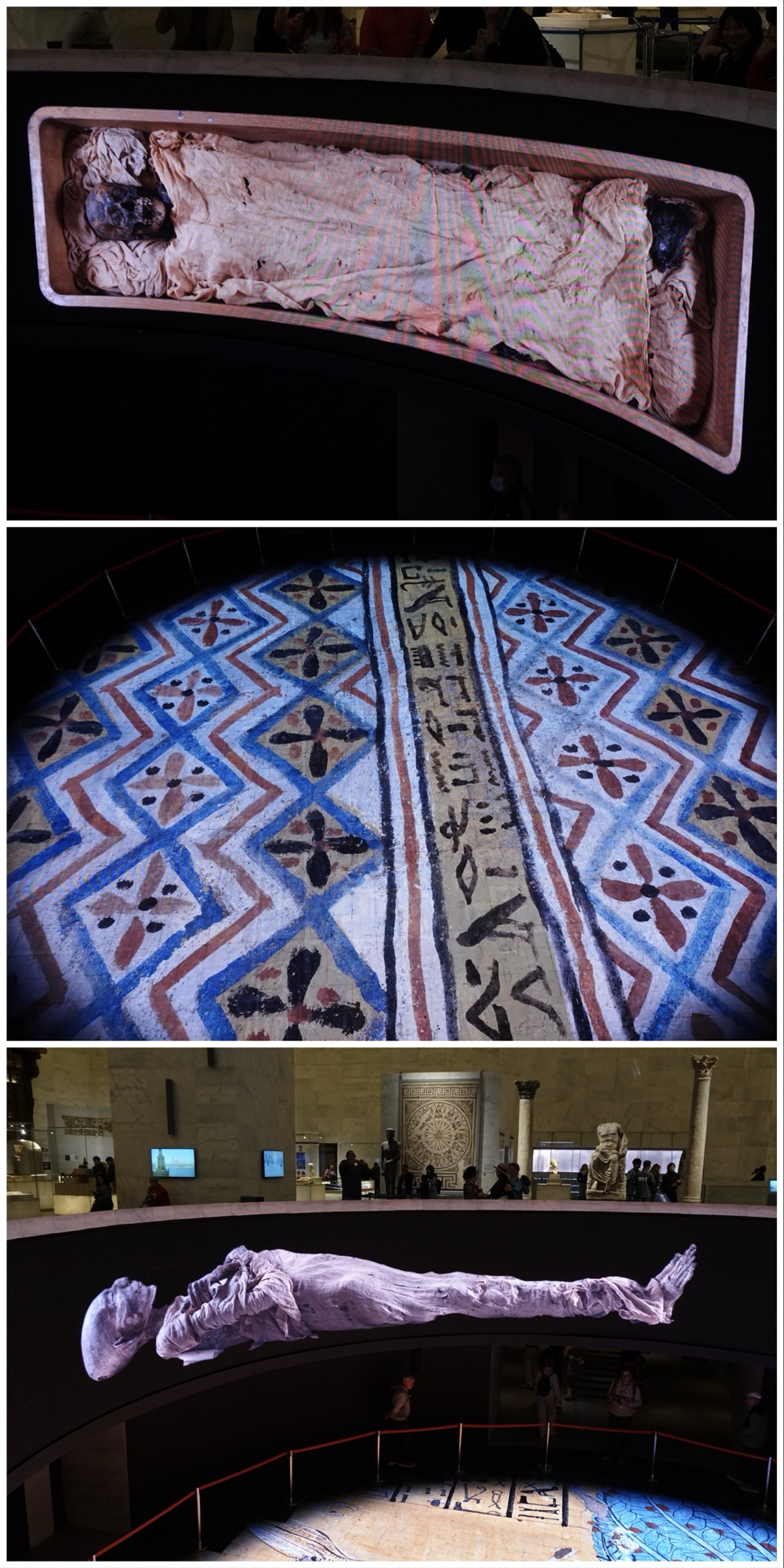

The damaged statue of Akhenaten, the son of Amenhotep III, who ruled as Amenhotep IV. He was the first Pharoah to pull back the power held by the priests of the Egyptians’ 42 gods by uniting the gods into a single god, Aten, requiring far fewer clergy. Concurrently he moved the capital from Luxor, and changed his name to include the name of that new god. Akhenaten was married to Nefertiti, who – according to new scholarly research – may have reigned briefly under an assumed name and a male disguise, like Hatshepsut . Akhenaten had no sons, but was succeeded after Nefertiti’s death by his nephew Tutankhamen, who restored the worship of 42 gods (making the priests very happy, and once again very rich).

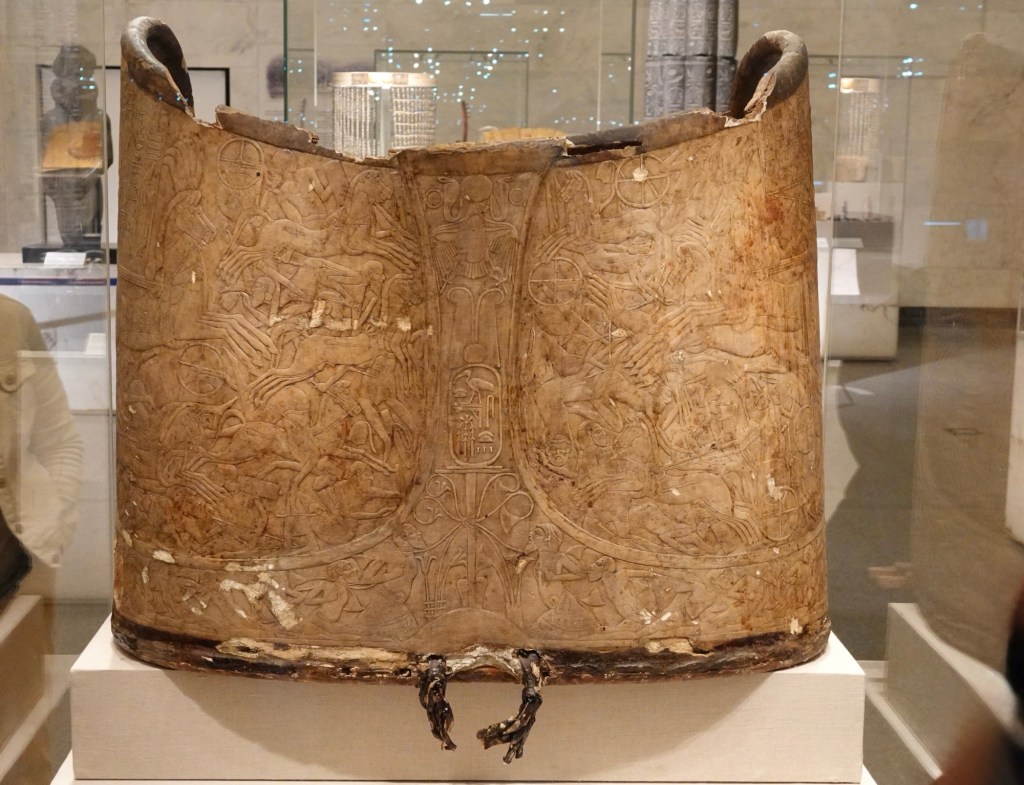

What would have been a fairly non-descript item to us (by comparison to statues and gleaming gold) was an item Walid described as one of the most important artefacts of the museum: a rare intact chariot shield dating to about 1200 BCE.

On the ground level of the museum more than 12,000 artefacts are displayed; in the subterranean level are the mummies.

Each mummy is housed in a room shaped like a burial chamber.

We “met” the pharoahs in order from the oldest mummy to the most recent. The 18 kings are: Seqenenre Taa II, Amenhotep I, Thutmose I, II and III, Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV, Amenhotep III, Seti I, Rameses II, Merenotah, Seti II, Siptah, Rameses II, IV,V, VI, & IX. The four queens are: Ahmose-Nefertari, Meritamun, Hatshepsut, and Tiye.

No photos, even without flash, are allowed. Even talking is forbidden; our breath adds dangerous humidity to the air.

Just as if we were entering a tomb, we headed down a set of stairs into the area where the mummies are displayed. Instead of beautifully decorated limestone walls, the chambers here are all shiny black granite. Perhaps it is a good thing that photography is not allowed, because when we are not concentrating on getting the best picture or the best angle, all that’s left is reading the interpretive signs and taking a really focussed look at each exhibit.

In each chamber, there was typically at least one of the pharaoh’s nested coffins on display, as well as the mummy of the pharaoh himself or herself. On one of the 4 walls, there was always a large brass plaque outlining the pharaoh’s accomplishments during their reign.

To say that we were awed by the mummies would be a gross understatement. The facial features preserved by the mummification process truly allowed us to get an idea of what each of the pharaohs looked like in life. Of course the skin is stretched over bone; muscles and flesh did not survive the desiccation process. We know that makes a difference, because features are not rounded out, and muscles of the limbs are completely missing making each body seem painfully thin.

And yet, each looks eerily lifelike. Hair has survived, and fingernails and toenails, and teeth between thin collagen-depleted lips, and delicately shaped ears, and proud chins.

In fact, I commented to Ted that I found it somewhat disconcerting that each of these very thin leathery-skinned mummies reminded me of newsreels of starving Somalis during famines and drought.

It’s another one of those thoughts that crosses my mind far too regularly: why do we value objects like these mummies as priceless, and yet value our fellow human beings so very little?

All through this tour of Egypt’s ancient archeological sites we have heard about the ancient Egyptian belief in the afterlife, and learned about how obsessed pharaohs were with preparing for the eternal life after their mortal one ended. Pharaohs like Ramses II, in particular, seems to want to put their mark on absolutely everything in an effort to be remembered. The fact that thousands of people visit this museum for the main purpose of seeing the pharaohs’ mummies means that in a strange way their quest for eternal life has been achieved.

Ted returned to the main gallery to take photos of some the the artefacts that most appealed to him, while I sat for a few minutes to record some thoughts while they were fresh in my mind.

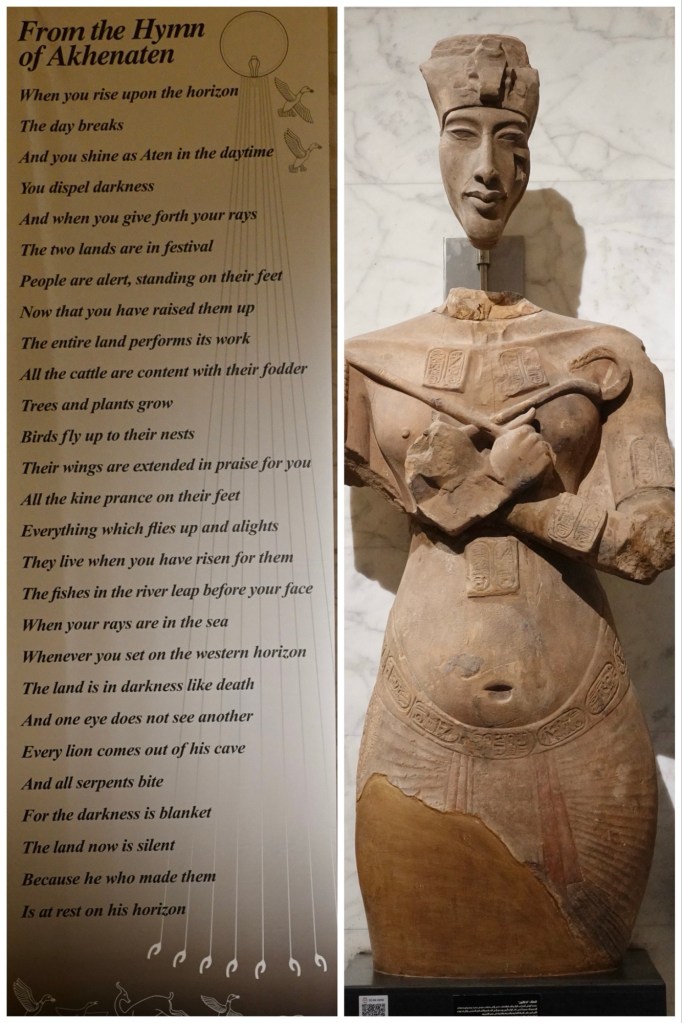

Nedjemankh was a priest of the god “Heryshef” at the city of Ahnas. His coffin is made of gilded cartonnage with inlaid eyes and covered with scenes as well as funerary hymns from the Book of the Dead had made it considered to be one of the masterpieces of coffins from the Ptolemaic Period.

Repatriated from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York / Ptolemaic Period (305 – 30 BC) / Gilded stucco

This statue is considered one of the oldest statues made in the form of the Sphinx for one of the ancient Egyptian queens. It is attributed to Queen “Hetepheres I” the daughter of the King “Khufu”. This rare form statue of queens may indicate her assumption of the throne, expressing the Egyptians’ appreciation for women, and their reverence for her as a mother, a sister, a wife, a ruler, and a goddess as well. (Taken from the museum’s sign)

This statue is one of three statues of King Merenptah which were recently found south of Mit Rahina, the site of the ancient city of Memphis. The statue depicts the king standing in the company of Mut, goddess of Thebes, the patron of kingship and the consort of Amun-Ra king of the gods.

New Kingdom. 19th Dynasty (1295 – 1186 BC) / Mit Rahina / Red Granite

A group of glass lamps decorated with multi-colored enamel, which were designated for lighting in religious establishments during the Mamluk Period. These lamps are distinguished by its floral decorations and inscriptions in the Naskh script, which depend mostly on the Ayat al-Nur. These lamps were lit by means of a wick of cotton or linen placed inside a glass container containing clean oil, usually olive oil. This group of lamps belongs to the Sultan Hassan School, Al-Nasir Muhammad Ibn Calawun School, and Al-Zahir Barqua School.

Mamluk Period – 8* century AH – 14* century AD / Glass

Then Ted popped outside to check out the view from the vantage point of the museum!s courtyard, while I popped into the gift shop to see if I could find a book about the mummies for our grandsons. While their previous experience with mummies has all been cartoons and movies, I’m hoping that this book with its real photographs and interesting stories about the pharaohs will ignite an interest in ancient history similar to what I had as a child.

A quick note about our final hotel stay.

Our last night before flying home was at the Intercontinental Cairo Citystars, attached to City Stars Heliopolis Mall. It clearly caters to foreign tourists, since the gorgeous Egyptian themed lobby had been decorated for Christmas, complete with a huge tree and a Santa, but my favourite was the sphinx holding poinsettias.

Our room was absolutely gorgeous. Despite the fact that we really couldn’t enjoy it to its fullest because we had a 3:30 a.m. departure to the airport, it was a terrific place to kick off our shoes and relax. We even managed a few hours of sleep before the 3:00 a.m. wake-up call that Viking had pre-arranged.

The included buffet style lunch and dinner were some of the best buffets we’ve experienced in any hotel, with the highlight definitely being all the wonderful Middle Eastern and European treats at the dessert bar.