We knew there would be no way today’s visit to the spectacular newly-opened GEM would be anywhere long enough, but still … what an experience!!

A couple of weeks before our trip, Viking sent an additional email to get us excited – as if we weren’t already!

The concept for the GEM was begun under the direction of UNESCO in an effort to ensure that Egypt had a “suitable” place for all of the artefacts already housed in Egypt as well as those that are now on display other countries, specifically the Rosetta Stone, which is in the British museum, the Zodiac from Dendersla Temple now in the Louvre, and the head of Nefertiti, which is in the Berlin Museum.

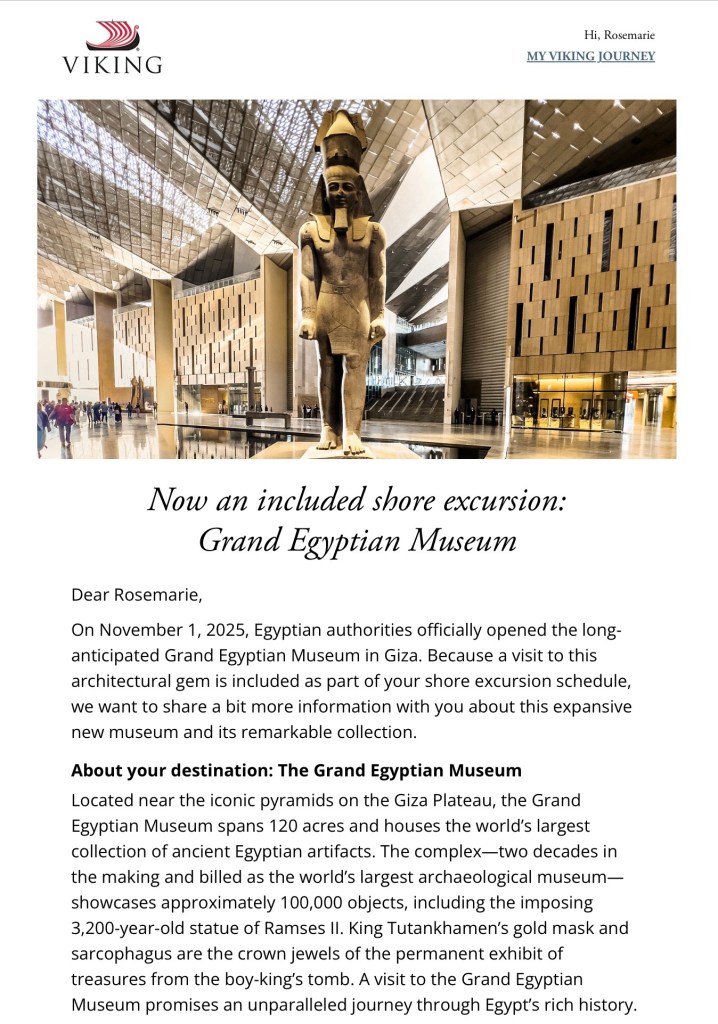

Apparently the exterior of the GEM when viewed from above looks like rays of the sunlight. It faces the three pyramids of Giza, which are visible through the viewing windows at the front of the museum.

On the exterior wall are 112 pyramids one for each of the pyramids that have currently been discovered in Egypt.

There is no way to photograph the entire exterior – the GEM is currently the largest museum in the world by floor area!

Although the design and construction began in 2004, when the Arab Spring uprising happened in 2011 construction was halted for almost 4 years. Egypt’s economy could not support this grand museum vision, but Japan volunteered to support up a large portion of the cost. The GEM’s original opening was slated for 2020 after completion of the building in 2019 and the artefacts being moved in from other museums. Unfortunately, Covid delayed that initial opening, and it was cancelled a total of three times before eventually having its grand inauguration at the beginning of this month. Within the first couple of days after the November 1 Inauguration over 40 million people walked through the GEM.

Today there are thankfully a more manageable number of visitors, and our group was there almost as soon as the doors opened for the day.. We had four hours in total at the GEM.

On the museum façade the transition from sandstone to glass is stunning. Imagine standing under the glass pyramid of the Louvre but 1000 times larger.

After passing through a gorgeous high-end food court that includes offerings from Egypt, France, and Italy, as well as the ubiquitous Starbucks, our first view was of the incredible grand staircase with artefacts that take us through the various ages of ancient Egypt. We’d get a closer look later.

But we had things to see before ascending.

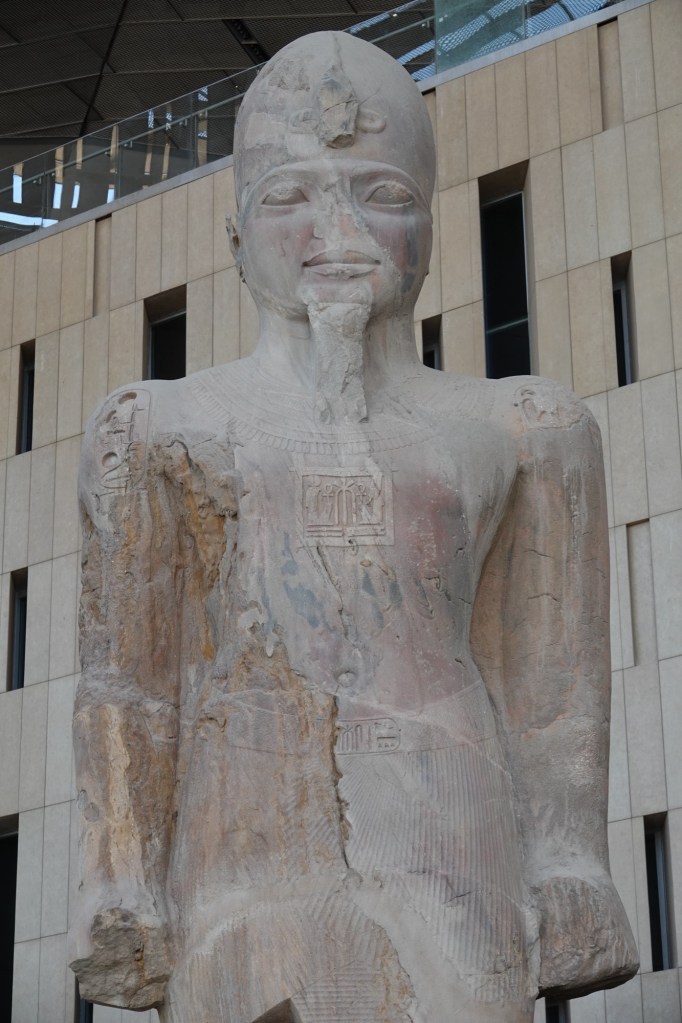

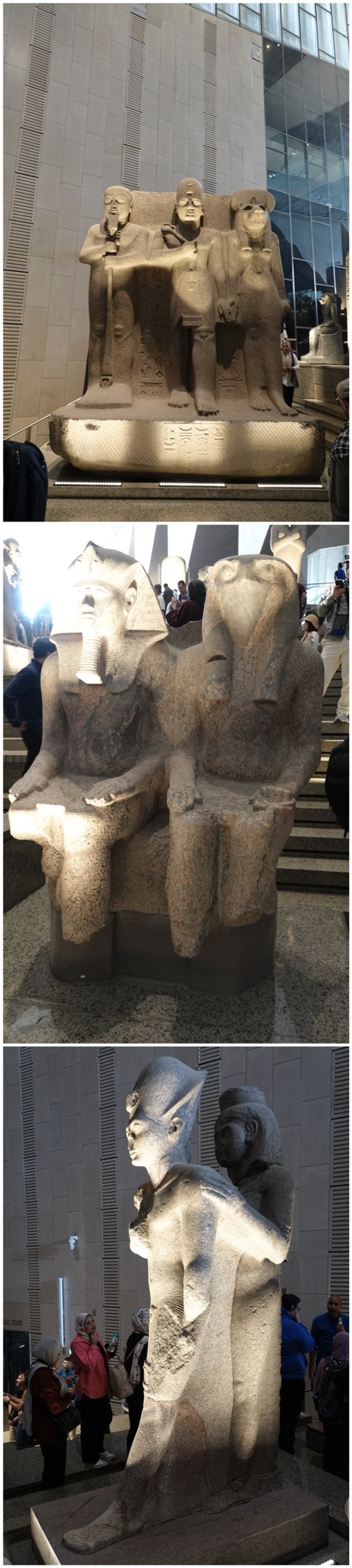

Our tour began under a huge limestone statue of Rameses the second, which was originally located in Memphis, and then in the old museum here in Cairo. Moving it from that location cost over 1 million dollars.

The large crack in it has been repaired, and the statue has been here since 2019.

From one statue of Rameses II we moved to an even larger one made of granite from Aswan.

Rameses II was Egypt’s most important pharaoh, ruling 67 years from 1250 BCE until 1183 BCE. This is one of more than 200 statues of Rameses II, although our guide explained that Rameses cheated a bit, erasing the names of other pharaohs from their statues and replacing them with his name. Rameses lived to be 92. The average age of a pharaoh at that time was 40; regular people to around 40. Of Rameses 35 wives, Nefertiti (his first) was his favourite. Only she has a tomb in the Valley of the Kings and Queens , and a huge monument at Abu Simbel.

A second boat has been found near his pyramid and is in the process of being reconstructed with the help again of Japan.

If Khufu was not a familiar name, it’s because the British referred to this pharoah as “Cheops”.

Secrets our Egyptologist revealed: a statue carved with a straight beard, open arms, or one foot forward shows a living pharaoh. A curled beard, crossed arms, or legs together means the person was dead at the time of sculpture. Both hands closed = in control of the country. One hand open = peace. Every element has a meaning.

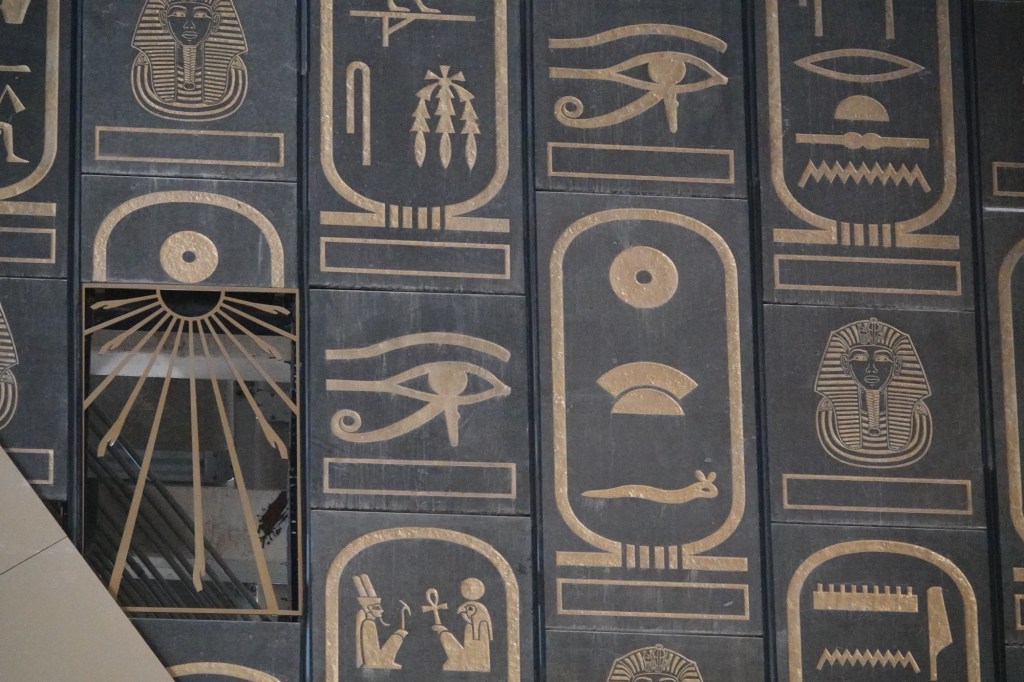

There’s another insider secret in the museum: one pharaoh’s cartouche is missing/erased from the wall of cartouches, and has been replaced with a window.

It is the cartouche of Rameses II, as modern day karma for him having erased so many other pharaohs’ names. But there’s redemption. Light shines directly through that window on just 2 days of the year (Feb 21 and Oct 21), when it shines directly onto Rameses’ face.

The ovals around the cartouches represent infinity (no beginning or end) and are ovals instead of circles simply so that there is enough space to hold a name. In ancient times only pharaohs’ names could be put into a cartouche.

Also in the entrance hall are two granite Ptolemaic king and queen statues that date to the Graeco-Roman era in Egypt, and were found under the Mediterranean Sea. They were previously in the museum at Alexandria.

The 30 seated statues on the side stairs are arranged in the shape of a pyramid.

Ascending the grand staircase (there is a moving walkway that ascends to each “stage” for those who cannot do stairs) are statues depicting the stages of a pharaoh’s life.

Stage 1 – becoming the pharaoh and worshipping the gods, depicted as pharaohs seated in a posture of worship.

Stage 2 – building temples to the gods, represented by pieces of various temples: entranceways, statues, obelisks, etc.

Stage 3 – the pharaohs shown on a par with the gods, represented by pharaohs being embraced by gods, or statues depicting the pharaoh and the God the same size.

Stage 4 – death, as represented by sarcophagi. Death is the most important stage because the afterlife is eternal.

At the top of the staircase, we are led directly to a view of the pyramids of Giza, because the pyramids were the place of interment for the pharaohs, hence being a part of death and eternity. Unfortunately with the sun shining brightly against the glass it wasn’t easy to get a good picture from inside the museum, but Ted managed !

At the top of the stairs are the museum’s 12 main galleries showcasing the different periods of Egypt, with artefacts that have come from many different parts of Egypt.

We skipped those 12 galleries, although our guide (shown above) explained roughly what was in them, in order to visit the highlight of the GEM: the King Tutankhamen galleries with their over 5700 artifacts.

Absolutely everything in these galleries was found in King Tut’s actual tomb, uncovered in 1922, and which was the SMALLEST of the 65 tombs found in the Valley of the Kings! That small size was not reflective of the pharaoh’s status, but of his young age; he died before his intended tomb was completed and was likely buried in a tomb intended for a high official but not a pharaoh.

We were in that tomb on our last visit to Egypt, and will be in it again this week. It is incredible to believe that all of this was originally in the 4 rooms of that small space!

Walking among these exhibits is when being guided by an Egyptologist who completed one of his two Masters degrees on aspects of the Tutankhamen finds is incredibly valuable. Walid was able to help us focus on the most important of the over 5000 items.

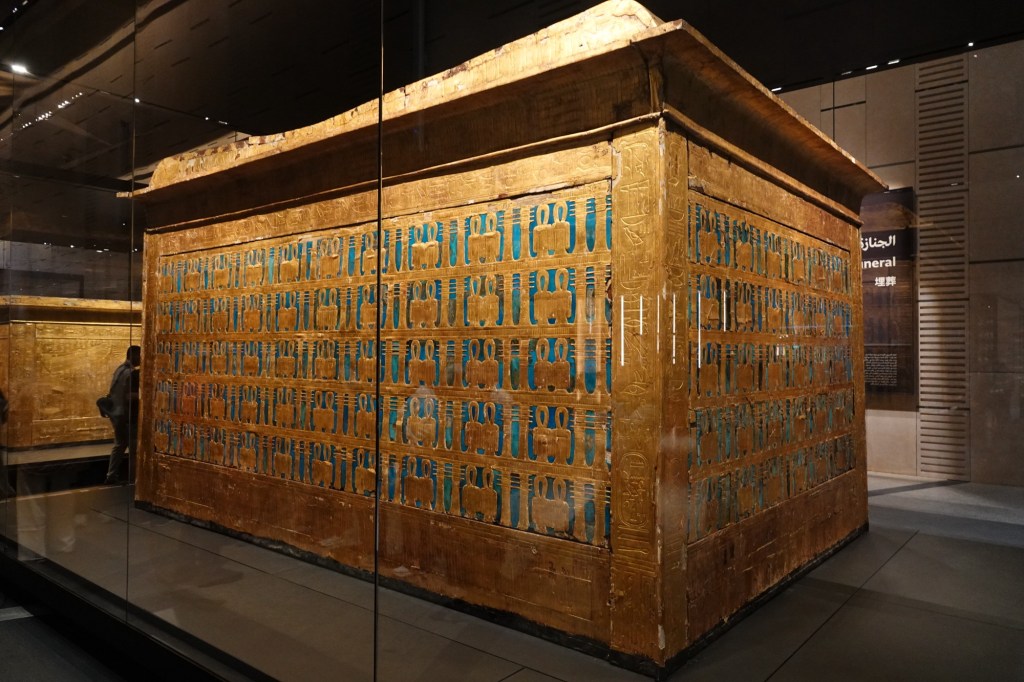

The first things we saw were the three “nesting” shrines that held the king’s sarcophagus.

Having been in King Tut’s tomb, we realized very quickly that these shrines are much too large to fit into the passage leading down to the tomb. It makes sense that they were built in the tomb. In order to remove them from the tomb they had to be cut into pieces and reassembled. It seems that the smallest of the four shrines was built in situ around the sarcophagus (the stone chamber built to hold the coffins) and then each successively larger shrine built around it.

The smallest of the shrines (below) would have been the one encasing the granite sarcophagus, and may even have been used in transit for getting the coffins to the tomb, although it would have been a tight fit through the tunnel.

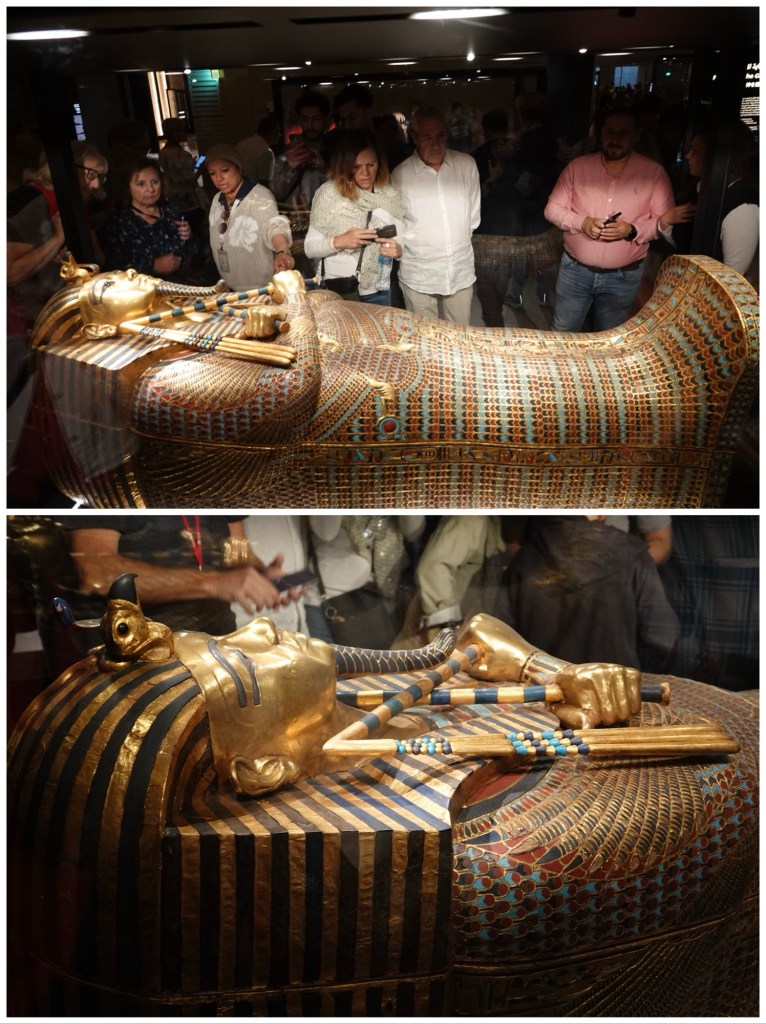

Inside the sarcophagus were 3 nested coffins. The multiple layers were intended as protection.

The 4 shrines and the 2 outer nested coffins are not made of gold, but constructed of wood and then painted with gold leaf.

The inner coffin, however, is made of 110kg/230lbs of 18 karat gold!

The golden mask that covered the king’s head was made of 10kg/22lbs of pure gold. The mask depicts the perfect face of the king so that his spirit would be able to recognize his body in order to return to it after its yearlong journey to heaven and back.

Howard Carter’s crew, while pulling Tut’s mummy with its golden mask from the coffin, broke the mummy’s body at the ribs, since the mummy was “stuck” in the coffin and they were intent on removing it.

The granite sarcophagus which held the coffins inside the shrines is still in the tomb, along with the damaged mummy itself, which is now too fragile to move. We’ll see it in a couple of days.

We moved on to some of Walid’s favourite things in the gallery.

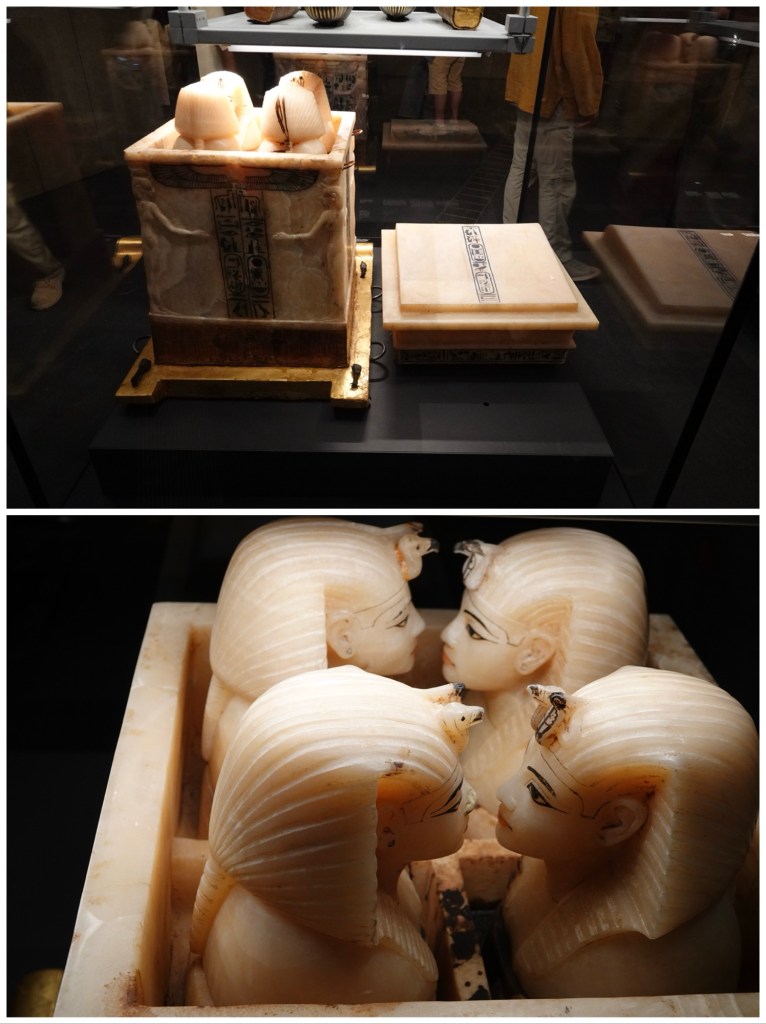

This large wooden box from the tomb’s antechamber is ringed with cobras for protection.

In addition to the cobras, Isis and her 3 sisters also protect the box’s contents.

Inside the box was another box, made of alabaster and containing four canopic jars which still contain Tut’s lungs, intestines, stomach, and liver. The alabaster heads are the jar stoppers!

Interestingly, the heart remains inside the body so it can later be weighed (in heaven) against a feather to determine whether it was good or bad. Equal in weight or lighter than a feather allowed access to heaven. It gives “feeling light as a feather” a whole new spin.

And the brain? Thrown away. “Because the brain is nothing after death.”

The two wooden tomb guardian statues originally faced each other outside the burial chamber. They each have the face of Tut, painted in mourning black.

King Tut’s three funerary beds have heads of hippos, cows, and lions – all symbols of protection. These beds were intended to carry the king’s treasures to the afterlife.

Tut’s sandals and finger gloves are made of pure gold!

Walid’s #1 favourite piece of the entire collection is not the golden mask of King Tut, but his gilded wooden throne.

On the back of the throne is a depiction of King Tut with his wife standing behind him appearing to apply oil to his body. Walid pointed out that each of the figures is wearing one of a pair of matching sandals, the shared footwear acting as a symbol of their connection through love.

On the throne’s footstool are three Nubian figures and three Asian figures from the Hittite tribes. Those people were the enemies of Egypt during King Tut’s reign, and were depicted on the king’s footstool so that he could step on them.

The alabaster jars at the end of the gallery were found in the antechambers, still filled with fragrant oils, including lotus oil which was reputed to impart eternal youth.

We had two hours of free time with so much to choose from that it was almost daunting. We walked around a bit more of the Tut galleries, to an area focused on the royal wardrobe. For anyone who thinks that linen doesn’t last, there were linen gloves that survived, taken from the tomb’s antechambers.

We passed a beautiful wall of hieroglyphics. If the Rosetta stone were here instead of in the British Museum, we might have been able to read them!

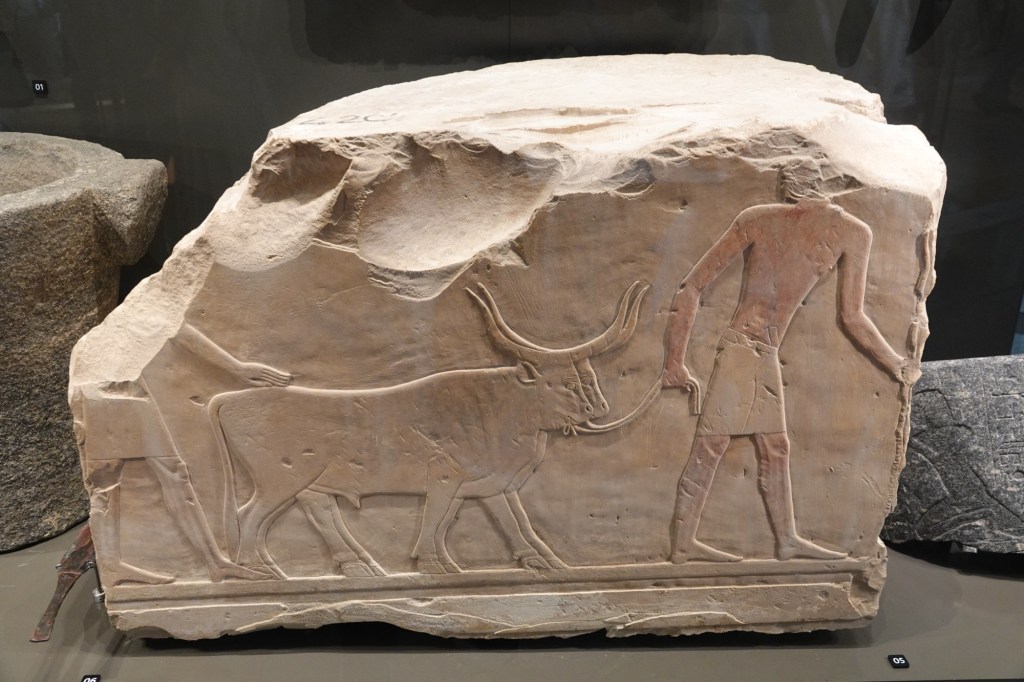

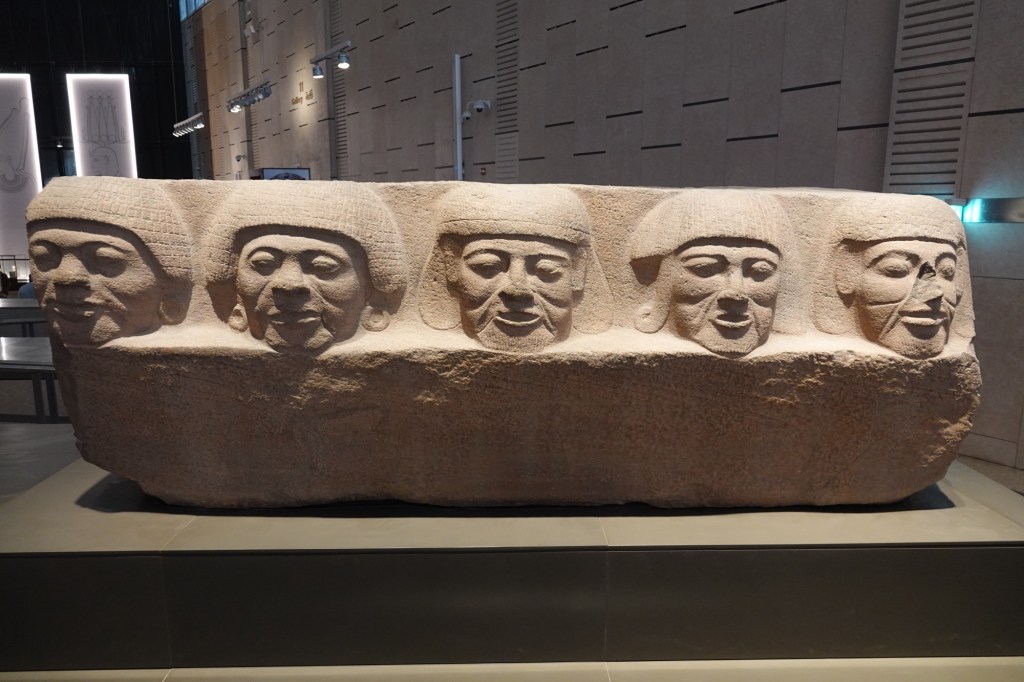

We took the chance to walk briefly through galleries 7, 8 and 9 which hold items from the new kingdom since our guide had suggested they represented the “golden age” of Egypt. We were amazed by stelae here covered in hieroglyphics, which have now been interpreted thanks to the finding of the Rosetta Stone.

I was intrigued by the very long toes on the feet of all the statues. I wonder whether that was actually a typical characteristic of Egyptians, but we don’t see many wearing open toed shoes, so couldn’t really do an informal survey.

Just a few of our other favourite things:

baboon, the symbol of Thoth, god of writing, wisdom, magic and the moon.

In a separate building adjacent to the museum are two boats that were found buried next to King Khufu’s Great Pyramid (about 2575-2545 BCE). Each one had been dismantled and hidden in a pit covered by rows of great blocking stones, waiting to be reused to transport him and his treasures to the afterlife. It has been presumed that these were same boats that were used to transport the pharaoh’s body and accoutrements from the capital in Memphis to the plateau, where he was been mummified and buried.

State-of-the art museums like the GEM (and Athens’ Acropolis Museum) make a mockery of the idea that only “Western” museums like the British Museum or the Louvre can properly curate and preserve the archeological finds taken from Egypt and Greece.

And as far as the argument that fewer people might have access to the items if they were returned to Egypt, I’d ask “fewer of what people?”. Certainly, in my own case, the fact that I only had access to pictures and stories in books for most of my life did not lessen my enthusiasm for ancient history. Today, access to the internet and video streaming means that anyone with a cellphone can “see” these wonderful artefacts.

It’s probably a good thing that some of the ancient wonders were simply too big to move – even though plundering huge slabs of friezes from the Parthenon, and “exporting” obelisks and the huge statue of Rameses II came close.

Now that the GEM has been completed, the UNESCO process for repatriating artefacts will hopefully move forward more successfully.

Speaking of things too large to move…

Our afternoon excursion was to the Great Pyramid on Giza Plateau.

I’m exhausted tonight, and we have to be up before 05:00 tomorrow for our early flight to Luxor, so that will be a separate episode.

Fantastic! Egypt is moving up my to-do list!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! gre

LikeLike

This was an incredible episode. As someone who will never get there (elderly), I feel as though your report was the next best thing. Thank you so much for taking the time/trouble to write it. Jan Lesliejanetcbl39@yahoo.com

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPad

LikeLiked by 1 person

We love sharing our experiences!

LikeLike

looks super cool, thanks. We’d go back just for this, thanks!!

LikeLiked by 1 person