05:00 The muezzin’s hypnotic call to prayer drowns out the car horns for a few moments.

06:00 Up for the day

06:30 Downstairs to the Rawi restaurant for breakfast.

07:45. Our first group orientation meeting, where we also got our QuietVox headsets.

08:45 On the coach.

No rest for these intrepid adventurers!

That said, we slept fairly well, and feel as if we’ve successfully transitioned to Cairo time, which is 10 hours ahead of Vancouver.

Ted and I absolutely loved our 2022 visit to the necropolis and step pyramid at Sakkara (Episode 246), and were thrilled to be returning today. This visit promised a much more in-depth experience.

The bonus in today’s excursion would be the Citadel of Saladin here in Cairo.

We had to drive about 45 minutes to reach the Sakkara complex, taking a route along one of the irrigation canals built alongside the Nile. This landscape was what Ted and I remembered from our last trip here: the contrast between downtown’s hotels and high-end shopping district with the arras of tiny family farms. If anything, the garbage in the irrigation canals has gotten worse in the past 4 years; the people and animals look about the same.

While we drove, our Egyptologist guide Walid gave us some perspective on what we were about to see.

112 pyramids have been found so far in Egypt, with the Sakkara step pyramid being the oldest not only in Egypt but in the world.

Each pyramid was built as a pharaoh’s tomb.

Egypt’s prehistoric period is considered to start in 5000 BCE, and the pre-dynastic period from 4000 to 3200 BCE. There are no written records for those periods.

The first ever hieroglyphics date to the dynastic period, which lasted from 3200BCE to 300 BCE, broken into old, middle, and new kingdoms. Today in Sakkara we would see the absolute oldest hieroglyphics!

Originally everyone lived on the east side of the Nile river (sunrise) and the west where the sun set was considered to be for the afterlife. In the predynastic periods, bodies were apparently buried in graves, in the foetal position, ready for “rebirth”, and simply covered with sand, but the Saharan black jackals often dug up and ate the bodies. No body = no rebirth, so around 3000 BCE the burial process was changed. Burial pits were covered by a “mastaba”, a rectangle of limestone cut from the nearby hills.

It seems it was the Pharaoh Djoser who was the first to commission a pyramidal tomb “cover”, and that was the step pyramid at Sakkara, designed by the ancient Egyptian architect Imhotep.

As we entered the Sakkara complex, we drove past an area of new excavation. No tourist access is allowed yet, but in just the last six months blowing sand off the desert surface – after using geological imaging tools – has revealed a complete new burial complex and a workers village. Modern machinery that allows large areas of sand to be blown around has made the uncovering of archeological sites much easier than digging would have hundreds of years ago.

Our first stop in the necropolis complex was the tomb of the Pharoah Teti of the 6th Egyptian Dynasty (2345-2181 BCE) that contains what are believed to be the first ever hieroglyphics.

Given that this pyramid is over 4400 years old, the collapse of portions of the exterior (likely dating to an earthquake 2000 years ago) is not surprising. It looks more like a hill than a pyramid.

What is surprising is how well preserved the inside of the pyramid is. It is a challenge to go into the pyramid, because the ceiling is low and the access steep and narrow. I remembered entering this tomb in 2022; it seemed less daunting this time for being somewhat familiar.

Walid reminded us that this is the easiest tomb to access, and eminently worthwhile for the chance to see the first and oldest hieroglyphics ever discovered.

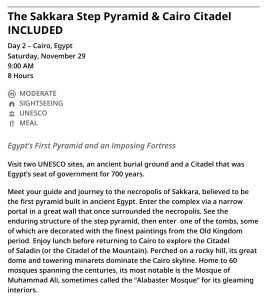

Across from the pharaoh’s tomb is an excavated tomb of the pharaoh’s son-in-law, Kagemni, who was also Chief Justice and Vizier.

Some of the (now) exterior friezes have survived. This tomb would originally have been buried under sand after being embellished.

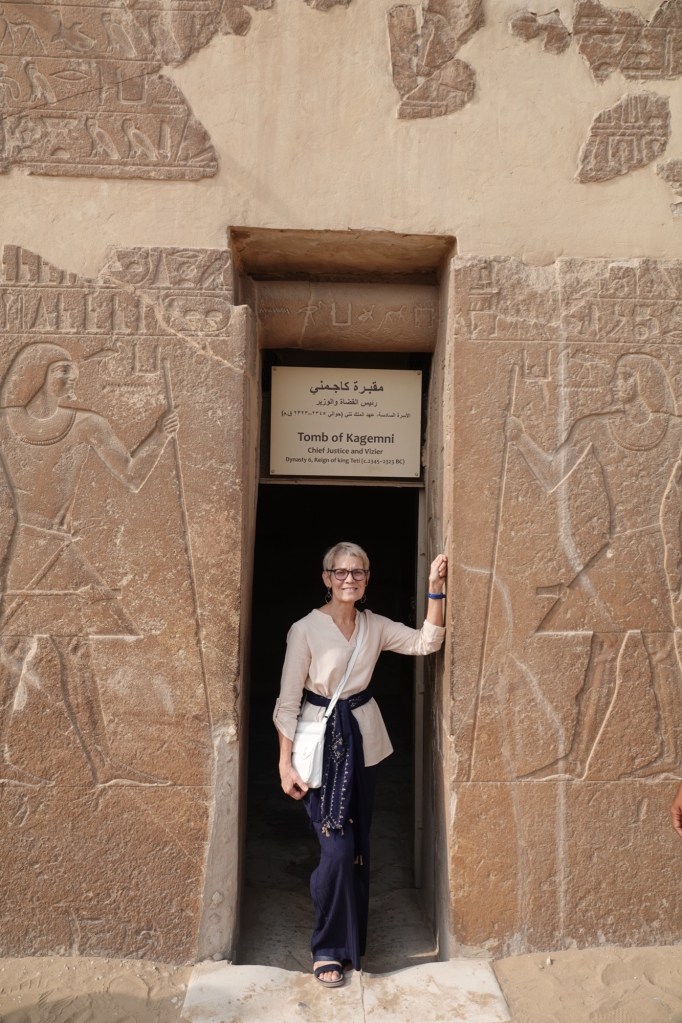

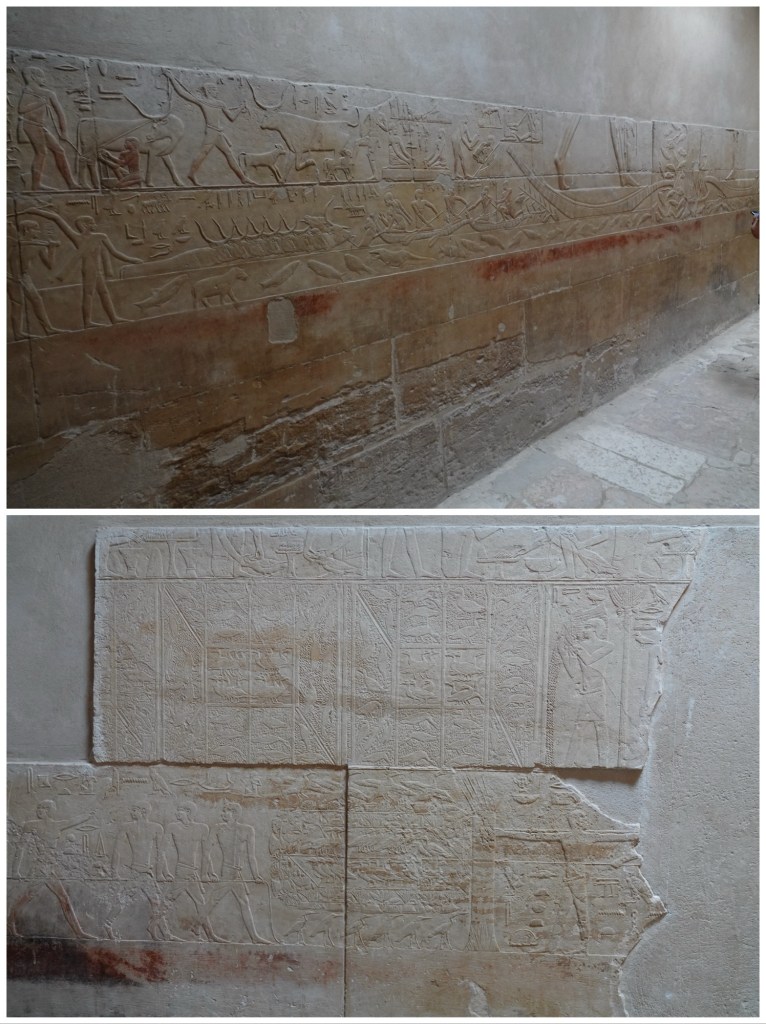

Inside this tomb we saw more examples of hieroglyphics, plus both raised relief and sunken relief friezes.

Where there was visible damage in the tomb, for example sections of friezes missing, we were told that predated their discovery in modern times. It’s really no wonder that the plaster-like compounds used to attach panels of decorative stone would have deteriorated over a period of thousands of years.

In the rooms peripheral to the actual burial chamber which would originally have contained the sarcophagus and mummy, there is very little – and sometimes no – colour because Kagemni died while the tomb was still under construction, and there was not time to do the final step of hand painting. To modern eyes it is quite beautiful the way it is, but we recalled that ancient sites that we have seen in Greece and Rome, which look today have monochromatic carved surfaces, were also originally very brightly painted.

Then it was time for the site’s pièce de résistance: the Sakkara step pyramid. This massive limestone construction is the first known use of limestone as a building material. Before that, mud bricks would have been the standard.

As an aside, while talking about the importance of this site we were reminded that Sakkara was part of Memphis, which was the first capital of Egypt during the old/first dynastic period. After Memphis, which was capital for about 1000 years, the next capital was Thebes (now called Luxor), and then eventually Cairo.

To get to the step pyramid we walked through the only remaining doorway in the huge limestone wall that originally surrounded the entire pyramid complex. The portion that we stood in front of is all that remains after over 5000 years of weather and earthquake activity. Everything except one rectangle of limestone above this original main entrance is completely unrestored. All of the limestone came from a quarry across the river that we passed later in the afternoon. After 5000 years, limestone and sandstone are still being quarried here!

The limestone blocks of the wall are incredibly smooth, making it hard to believe that they are 5000 years old. The smoothness is due to the stone being polished using sand, something of which there is no shortage here in the Egyptian desert. Looking back at the entrance gate from inside, we could see the difference between the surface of the polished stones and unpolished ones.

We entered the “hall of columns”. Here there are two rows of 20 columns that originally supported a roof very different from the flat concrete one installed by the Egyptian authority 50 years ago. The original roof would have looked like logs. There is one small section of original roof still remaining at the top of a small section of the hall of columns.

The columns create 40 “rooms”. Ancient Egypt had 42 states, each of which had its own God, totalling 40 “good” gods and 2 “bad” gods. It is believed that each of these small rooms was originally intended to hold the statue of one of those 40 good gods. The statues have not been found, although archeologists are still hoping that may be a pending discovery.

And then there it was!

Walid told us a lot about the design and construction of the pyramid.

The most important thing of course is the pharoah’s actual burial chamber, for which Imhotep had a deep shaft that goes down 92 feet dug. The intent of placing the burial chamber so far underground was to deter both jackals from exhuming the body and grave robbers from pillaging it. Unfortunately, the original burial chamber that Imhotep designed was too small for the pharaoh’s liking. It had enough room for the pharaoh’s body, but no space for the food and drink and treasures that the body would need during the 365 days when its spirit was making the trip to heaven to reserve a place. (Aside: Mummification was a strategy to preserve bodies during that year’s absence of the spirit. That also explains, I suppose, needing food, belongings, and companions to eventually take to heaven.) To solve that size problem Imhotep cut 11 more shafts, creating 12 “storage” chambers in total. All 12 chambers were covered by a mastaba, but the addition of the new chambers created a mastaba that was rectangular instead of square – not suitable for the pyramid that the pharaoh wanted erected as extra protection for his tomb. Imhotep had to add another section of mastaba in order to recreate a square base for the pyramid.

Today the step pyramid has visible blocks, but when it was built, the entire pyramid would have been coated in smooth plaster, creating six smooth flat steps that must have gleamed in the sun. Each side the of the pyramid measures 237 feet and the pyramid is 237 feet tall.

So why 6 steps? 26 centuries BCE when Djoser lived and died, it was believed that the spirit that left a body had actual legs and would “climb” to heaven and back. That 365 day round trip involved 6 steps up, and 6 back down.

Of course, there were souvenir vendors, but fewer and much less aggressive than in high tourist season, which is now over.

Surrounding the pyramid are other remnants of limestone constructions from the same era. They all look far too new to have been built 5000 years ago, and yet…

From the Sakkara Complex we drove to the Sakkara Carpet Weaving School, where the students range in age from from nine to twenty. The primary school students work with wool (from New Zealand); the middle school students work with Egyptian cotton and bamboo; and the senior students work with Chinese silk. Not only is there a gradation in materials, but in number of knots ranging from 100 in wool for the youngest students to a maximum of 1225 knots per square inch by an experienced artisan in silk!! There were young students here on the weekend, just experienced weavers.

I got to make ONE knot! It really made me appreciate the incredible speed and precision of the weavers.

Egyptian handmade rugs are considered number one in the world, ahead of (in order) Iran, Turkey, India, and now China.

In addition to gorgeous rugs, there were also Egyptian cotton tapestries for sale. Just imagine knotting these patterns!

We couldn’t afford a single piece. It’s a good thing we don’t have a home to decorate.

Next it was time for a food break.

As we arrived at the restaurant for our barbeque lunch, we realized that it was the same restaurant Viking had taken us to four years ago on our first world cruise.

We were greeted by traditional musicians, who invited me to dance with them. Having lingered to get a shot of the entrance without lots of people in it, Ted was too far behind me, so there is no evidence with which to make our grandsons cringe.

The food was still just as delicious: barbecued kofta kebabs, lots of eggplant dishes including baba ghanoush and moussaka, fresh Egyptian bread, grilled chicken, stuffed grape leaves, falafel, and much much more – even pasta and French fries for the less adventurous. Dessert was sweet potatoes (mashed and topped with béchamel sauce) , and various phyllo and semolina pastries, plus coffee or mint tea.

Then it was off to the Mohammed Ali mosque (not that Mohammed Ali).

Along the way, more typical roadside activity,

Unlike churches and cathedrals in most of Europe, most active mosques in the Muslim countries we’ve visited were not open for tourist gawking and photography. The Hagia Sofia and Blue Mosque in Istanbul allow tourist access (Episode 255) but on our visit to Morocco in 2023 only the incredibly huge Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca allowed tourists inside (Episode 435).

The citadel of Saladin dates to the twelfth century, built as a defence against the crusades, which didn’t end up actually reaching Egypt. The citadel was never used as a fortress against the Crusaders, but later when Egypt became part of the Ottoman Turkish empire, it went into use as the seat of the Ottoman installed king, adding a palace within the citadel walls.

The mosque we’re visiting within the citadel only dates to 1830-1852, and is named for Muhammad Ali, who was installed as King of Egypt and Sudan by the Ottomans to replace the previous ruler who was supportive of Egyptian independence. While the mosque is officially the Muhammad Ali mosque, it is also known as the citadel mosque and the alabaster mosque, the latter for its stone interior.

The domes of the mosque are made of wood covered with sheets of silver (although frankly everything in Cairo seems to be the colour of the sand coating the city), the exterior of the mosque is sandstone from the local quarry, and the front façade and interior walls and columns are alabaster from Luxor. The marble inside the mosque is from Lebanon.

The mosque is somewhat unique that it has two minarets and was therefore assigned two muezzin to make the call for prayer. Its original single minaret directed the call to prayer sound southward, and people living north of the mosque didn’t hear the call, hence the building of the second minaret. Walid quipped that the muezzin in modern day mosques is often a “bigger” man because they no longer get the exercise of climbing to the top of the minaret five times a day; 90% of all calls to prayer are now done using an automated speaker.

In the square court of the mosque, a wedding was being set up, complete with moveable chandeliers. The square is surrounded by columns topped with lotus flowers. In the archways created by the columns are ceilings painted with beautiful, orange, terra-cotta blue, and white designs.

The clock on the tower in the mosque courtyard was a gift from the country of France. In return Egypt gave France the Ramses II obelisk from Luxor. Unfortunately the French clock never worked. The obelisk still stands in Concorde Square in Paris. Worst trade ever.

There are seats around the ablution centre (below) so that hands, face, arms and feet can be washed before going into the house of prayer. This original ablution centre is no longer used; instead there is an area in the basement of the mosque where people can wash before prayer. What is most impressive about the ablution centre is that the entire thing including its eight columns was made out of a single block of alabaster!

After donning shoe covers, we went inside the mosque. The decoration truly is beautiful, and perhaps an argument could be made that it is even more beautifully decorated than Istanbul’s Blue Mosque, but in my opinion it is not even close to as impressive as the Hassan II mosque in Casablanca Morocco.

There were several weddings happening at the mosque with brides and their attendants wearing absolutely stunning gowns, and happy to have their photos taken.

Within the citadel walls and beside the mosque, Mohammed Ali’s former palace is undergoing a multi-year restoration project by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities. In 3 to 4 years it is expected to be accessible to tourists.

The citadel currently also houses the Egyptian National Military Museum, which we did not visit.

We debated long and hard as to whether we would join the optional dinner excursion to the Khan El Khalili Market. I really wanted time to sort photos and write (and there is precious little free time on this tour), but I also wanted to see the 1,000-year-old market, and Walid raved about the 5-star restaurant Viking had booked for dinner. I may have to reconcile myself to not posting our blogs as promptly as I’d like.

Walid forewarned us that the market was not a place to shop, since most of the vendors are selling “authentic” Egyptian souvenirs made in China. The market was a place to experience though.

In hindsight, we probably should have foregone the excursion. At a cost of almost $200CAD per person, it did not deliver an experience to match the price tag.

The market paled in comparison to the markets of Marrakech and Istanbul, and the food at the restaurant, while typically Egyptian, was nothing special: hummus, baba ganoush, grilled eggplant, flatbread, falafel, rice, stewed okra and tomatoes, phyllo pastry stuffed with ground meat, stewed beef, and rice pudding were all no better than the food we’d been served at our included lunch – and while the venue was pretty, the service was rushed and lacklustre.

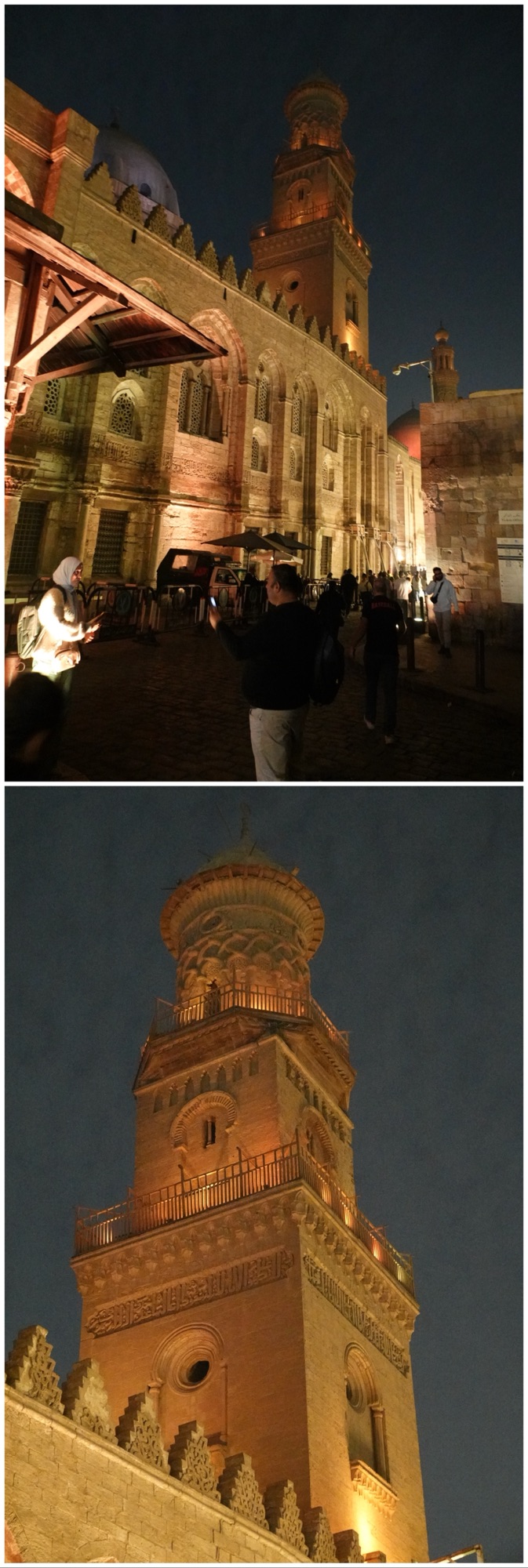

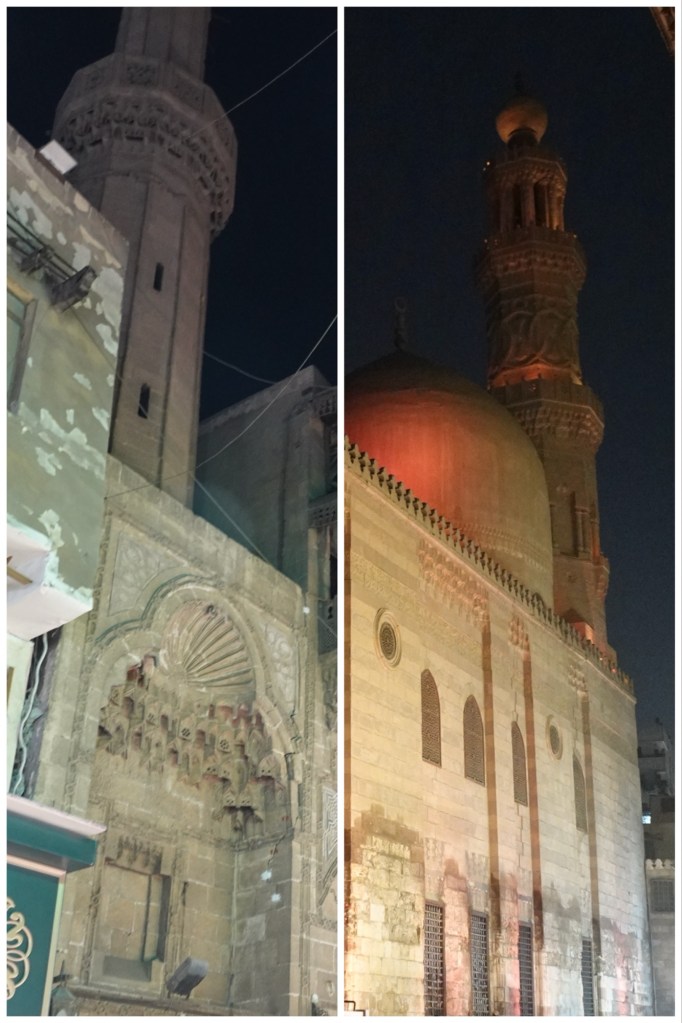

What was good about the excursion was the opportunity to see several really old mosques within the streets of the market. We learned that the age of a very old mosque can be narrowed down by observing the shape of its minaret. Mosques within minarets comprised of 2 square layers topped by a cylindrical one are 800 years old…

… and those with entirely cylindrical minarets are 1,000 years old.

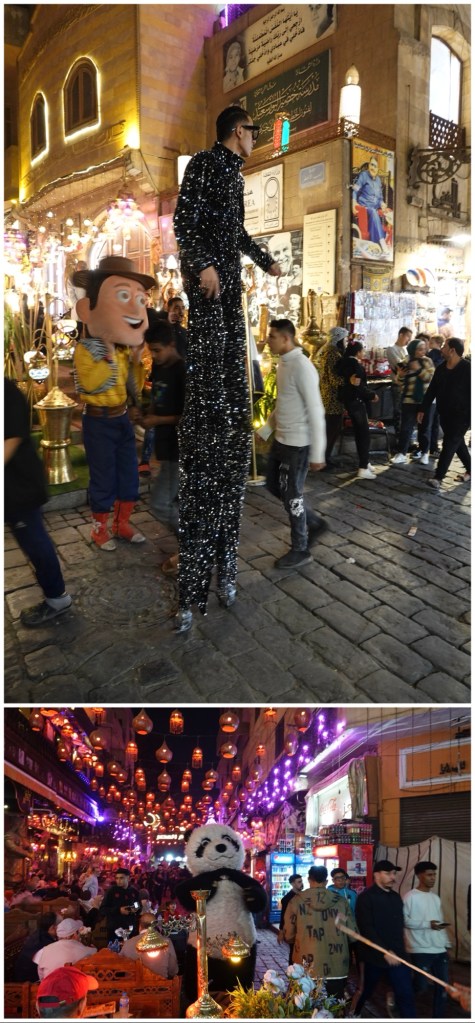

One particular aspect of the excursion was “exhilarating” : the actual process of walking through the market.

Imagine narrow unevenly paved streets lined with shops, each with a vendor out front trying to lure customers in. A riot of lights, colours, and sounds.

Imagine lots of litter along the sides of any space not actively operated by a business.

Imagine stray dogs and cats sleeping on the road and sidewalks, or simply sauntering between the crowds.

Imagine thousands of people, mostly locals, strolling the streets, headed for the shops and restaurants.

Now imagine mopeds and motorcycles sharing those same streets, honking and swerving between the pedestrians, driving right up behind you. Our security guard guided me out of the way several times; a motorcycle actually drove (slowly) into the back of Ted’s foot!

Add the occasional car filled with partygoers. And a small truck or two.

Then have the DJ’s in the nightclubs start spinning, and the street performers come out.

Absolute bedlam.

But, as Walid said, “it’s a true Cairo experience”.

Note: Ted wasn’t hurt, and our tour bus later drove down two of those same market streets in order to get to the main road back to our hotel!

It was quite a day.

I don’t post often enough telling you how much I enjoy your blog, but I really do. I have 2 friends doing this trip in February and I’ve sent them your link. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Always glad when we can be useful

LikeLike

Great reporting as always.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s so interesting to see the sights through your eyes and lens. It doesn’t look like we’ll get to the Saladin complex or Muhammad Ali temple on our trip in May, so I’m experiencing it vicariously.

I notice that you’re wearing sandals for the pyramid visit. Did that work out okay, or would you suggest closed shoes? How hot were you in long sleeves? Clothing suggestions are welcome, although we will be there in hotter weather.

We do have a visit planned to Khan Elkhalili (with lunch) during the day, so our experience will be different from your night visit. Maybe we can get back there on our own that evening.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We saw lots of folks talking about not wearing sandals, but I looked back and saw that in 2022 I wore them all the time. I’ve brought runners but have yet to wear them.

As long as you’re surefooted, I’d say any footwear except thongs or high heels (lol) would be fine.

Long sleeves? Better in the hot sun than sleeveless – just make sure they’re lightweight cotton/linen/gauze.

LikeLike