On our last day of the cruise, docked on the Danube in Vienna, we chose to sleep in. My head was stuffy, and once awake I just wanted a leisurely morning to curate photos, write, and drink about a gallon of chamomile tea with honey and lemon.

We both needed a relaxing day – so relaxing, in fact, that I didn’t even write my diary, so here is that day’s entry out of order and a couple of days late.

It’s funny how visiting a new place EVERY DAY can be as physically exhausting as it is mentally invigorating.

We’d already agreed that we would choose just one thing to do on our last day, and decided that one thing would be visiting the Albertina.

A highlight of that museum is the State Rooms (as opposed to private living quarters); a few were not accessible due to a special event, but those we did see were as wonderful as I had hoped.

Maria Theresa allowed only her favourite daughter, Archduchess Marie Christine, to freely choose a husband: Prince Albert of Saxony. On the occasion of their marriage in 1766, she provided her daughter with a considerable dowry. It consisted of large estates, the most precious jewellery and an enormous fortune. Archduchess Marie Christine thus became an extremely affluent woman.

In order to compensate for the class distinction between the Archduchess and Prince Albert of Saxony, Albert was given the Silesian Duchy of Teschen. From this point on he bore the title of Duke of Saxony-Teschen. Maria Theresa made her son-in-law a field marshal, and later Governor General in Hungary (Locumtenens), as well as supreme commander of the Hungarian troops (Captain General).

The couple subsequently resided in the castle in Pressburg (Bratislava), which Maria Theresa arranged to have extensively renovated and richly equipped with paintings and furniture.

The marriage of Archduchess Marie Christine and Prince Albert of Saxony-Teschen remained childless. Marie Christine therefore adopted the already 20-year old Archduke Carl, the third-born son of her brother, Emperor Leopold Il, in 1791. This meant that the enormous fortune remained within the House of Habsburg-Lorraine.

After the Archduchess’ death, Carl and his wife, Princess Henrietta of Nassau-Weilburg, and their six children lived in the Albertina palace. This is one of the rooms he had redecorated.

Different varieties of the palmette motif, an ornament for buildings or decorations popular since Antiquity, appear in the parquet floor.

Thinking about the floors we walked on, the one in the Audience Room below was the most complicated design we’ve seen in a wooden floor.

The room referred to simply as the “Rococo Room” really lived up to its name.

Looking up at the chandelier gave another glimpse into the artistry that went into its creation.

The “Wedgewood Cabinet” (small room) owes its name to the azure blue plates in the wainscoting, which were produced in the world famous English porcelain manufacture of Joshua Wedgwood.

We got a glimpse of the “Spanish Apartment”, best described by its signage:

Probably my favourite pieces of art from our visit were those few chosen to be presented in the State Rooms.

The Albertina – founded by by Duke Albert of Saxe-Teschen, and names fir the combination of his and his wife’s names (Albert and Tina, from Christina) – has arguably the most important and comprehensive collection of drawings and graphic art in the world. As Empress Maria Theresa’s son-in-law, Albert commanded the highest military and political offices of the Habsburg Empire; plus, he had at his disposal the considerable wealth of his wife the Archduchess. From 1776 (the year of their “Grand Tour” onwards, Duke Albert collected over 200,000 masterpieces, including works by Albrecht Dürer, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raffael, Rubens and Rembrandt.

The works of Albrecht Dürer are amongst the most famous at the Albertina, and were also some of my favourites. As the sign in the room explained, “Where observation of nature is concerned, this master of the German Renaissance from Nuremberg represents an unparalleled high point in art history.”

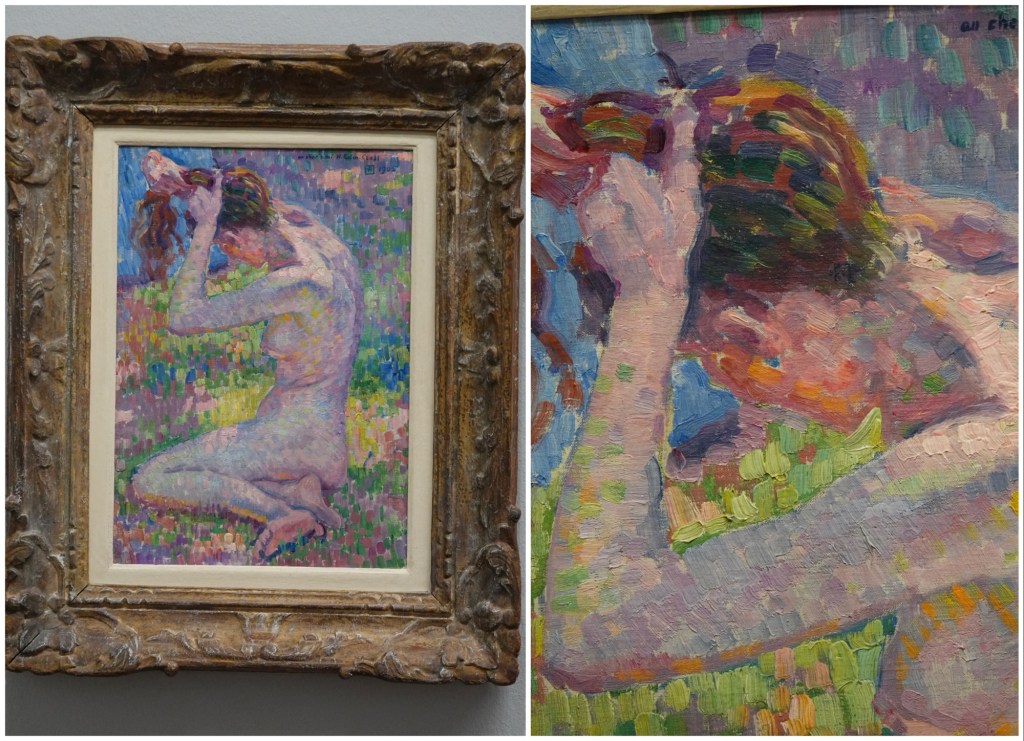

Much of the rest of the Albertina’s art collection – other than what was in the State Rooms – does not date to the time of Maria Christina and Albert, and honestly was mostly (with a few exceptions) not to my taste. While the Duke and Archduchess established a vast collection, it was almost exclusively graphic arts. It has since been supplemented by significant private loans and acquisitions, most notably the Batliner and Essl Collections, featuring impressionist and post-impressionist paintings. Obviously anything newer than 1822, when the Duke died, was not part of the original collection.

Ted took photos of a few of the pieces that we liked.

There were several Art Nouveau style pieces that I quite liked.

I thought I might enjoy (if that is the right word) the somewhat macabre exhibit called “Modern Gothic”, despite the fact that I knew there’d be at least one Edvard Munch included, and his work positively depresses me.

The “Gothic” work I enjoyed most was the 8-panel “Dance of Death”, in scenes that are like story chapters, by Robert Budzinski, inspired by a series of Hans Holbein’s woodcuttings on a similar theme. It was the last panel that made me smile.

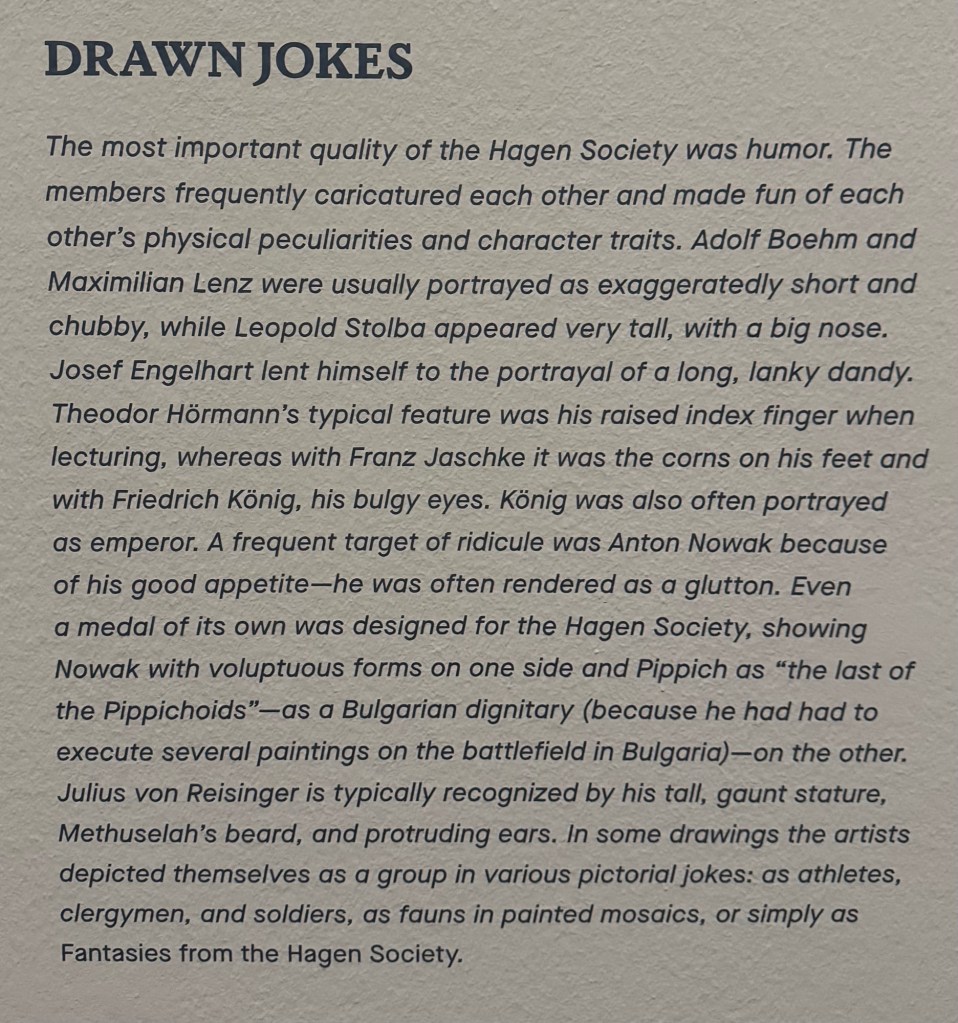

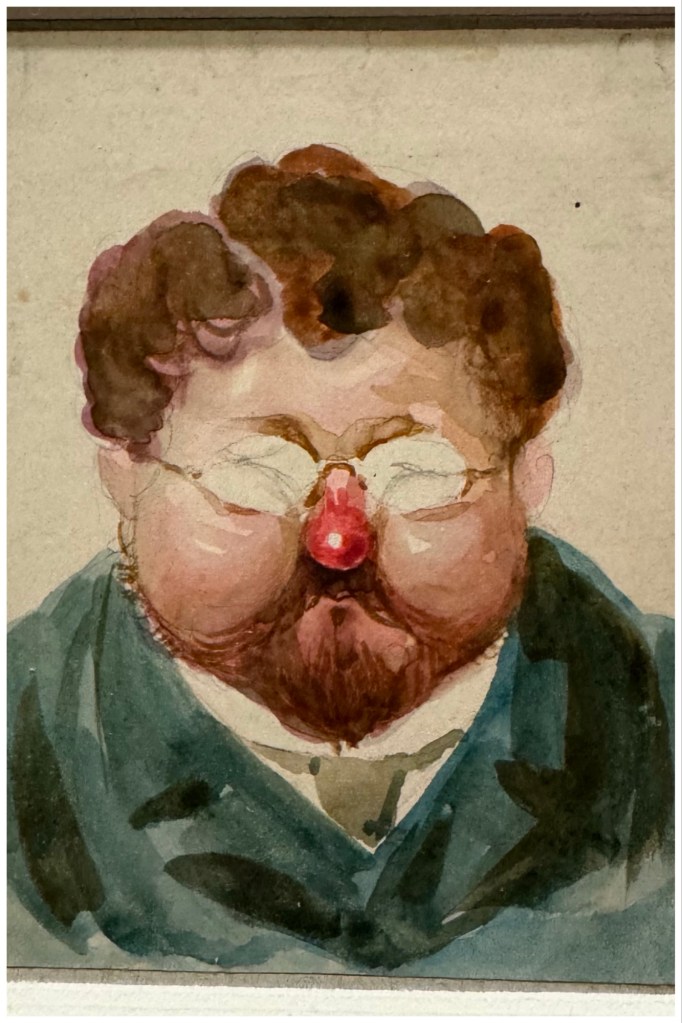

In a separate set of galleries, exhibits under the theme “Bohemian Vienna” were my favourite of the Albertina’s current displays. The drawings completed by a group of artists who caricatured each other and society in a Viennese café really amused me.

Here is a rough English translation (as posted in the museum) of the dedication by Ernst Stöhr in the center of the work above:

The painters are just very “special” people,

half asleep during the day, they become ingenious at night.

Hanging around at the coffeehouse they begin drawing away.

Were they always that diligent, each of them would own a palace.

Ideas come along like starlings,

and with the hands working swiftly, no table will stay blank.

As if it were to remain there eternally!

No one prepared to move it an inch-yet in the morning the waiter grumbles and wipes away the whole thing.

That’s why I began thinking:Wouldn’t it be wise if I bought a book for these crazy people?

You are supposed to draw into that book, instead of constantly drawing on the table!

One puts up with it when on a scrap, not just for a…

…swipe.

(pencil on paper) by Friedrich König

Arted out (is that even a thing?), we strolled to the Café Museum on Operngasse, half way between the Opera House and Karlsplatz, for one last Viennese coffee break. The waiters here are in traditional tuxedos; the senior waiters all in black, the juniors in white dinner jackets. The clientele are in a mix of tourist casual, and opera-going formal, all enjoying the wonderful coffees and pastries.

Bottom right: a traditional Viennese Melange (mild espresso served with steamed milk and an airy milk foam on top)

And that only left us saying “Servus” and “auf Wiedersehen” to Vienna… until next time!

(In Austria, “Servus” is used as both a greeting and farewell. It derives from the Latin word “servus” (servant), but today simply means both hello and goodbye.)

Arted out is definitely a thing! What a range of things to take in in one day — and all at one institution! Thanks for taking us along.

LikeLiked by 1 person