Once again today was a day when I took the opportunity for a class on my own after Ted’s and my joint morning excursion “Step Back in Time in a Charming Locale, described as “immerse yourself in the fascinating culture of Novi Sad during a walking tour.”

But first, breakfast: pumpkin “bundevara” with honey and cinnamon.

We docked this morning right in the city of Novi Sad, where a huge Austrian fortress called the Petrovaradin overlooks the city from the opposite bank of the Danube. The Fortress, built from 1692 to 1780, during the reign of the Habsburg Monarchy, is surrounded on three sides by water which made it almost impregnable.

In the other direction, a modern era arched bridge.

The city of Novi Sad is located on land that was originally swamp. Our guide Miroslav joked that the original inhabitants were not ancient tribes, but snakes, frogs, fishes, and mosquitoes. Much of the city is on “reclaimed” land; Novi Sad actually translates as “new plain”.

We were told that at one point Novi Sad was bigger than Belgrade. Our guide said that “while Belgrade was still a Turkish kasbah, Novi Sad was already a proper Austrian city.”

We walked from the shore up Danube Street, which 300 years ago was the actual Danube.

A very square (if a square can be “very” anything) modern art gallery built during the communist era in Soviet brutalist style is right beside a beautiful Habsburg style 1847 building that now houses the Museum of Northern Serbia. The contrast is somewhat disconcerting.

Despite the area having been swamp, it did have Roman settlements dating back almost 1700 years. Not just snakes and mosquitoes after all. The museum holds a good selection of locally found Roman artefacts and helmets; on the lawn are a few artifacts.

In 2022, the EU awarded Novi Sad the title “A Capital of European Culture”, even though they are not yet part of the EU, because of the significant mixture of cultures that are preserved here.

A second huge museum with wrought iron window grates was once a prison.

Beside it is Novi Sad’s marketplace.

Like markets we are seeing everywhere, there is of course clothing from China being sold in some of the stalls, alongside local produce and local handicrafts.

After admiring gorgeous peppers and tomatoes, and mouthwatering meats and cheeses, we stopped to taste a local snack, uštipci (fried yeast dough balls) with a variety of both sweet and salty dips: plum and apricot jams, salty curdled milk, fresh cheese, and red pepper spread.

After the revolution in 1849, only about four or five houses in all of Novi Sad survived. That means that all of the houses now are in a middle European style except for their windows. In the 19th century, when people here spoke German, Hungarian and Serbo-Croatian, these windows which opened made this street a true information centre for gossip. There are still occasionally German/Yiddish words used here; “kibbitzing” for gossiping is one of them.

The city is multicultural, having about 27 nationalities represented, although about 70% of the population is Serbian. There are Roman Catholic churches dating to the Austrian period, but also orthodox churches, protestant churches, and synagogues.

The sign on the library is in Serbian Cyrillic, Hungarian, Latinate, an unfamiliar (to us) language called Ruthenian, and SerboCroatian. I may have the order mixed up, since only the Hungarian looked familiar.

From Danube Street we turned onto Dragon Street, named after one of the most famous citizens of Novi Sad, the famous poet and doctor Jovan Jovanović Zmaj, whose last name when written in Cyrillic looks like the Serbian word for “dragon” .

The bishop’s palace in coral and yellow is on the main square.

Dragon Street is a pedestrian mall, but that doesn’t prevent Novi Sad’s aggressive cyclists from racing among those on foot. The city has long been known as a “cycle city”.

We passed the Roman Catholic church, dedicated to Saint Mary, with its tall stained glass windows and multicoloured ceramic tile roof in green, yellow and purple, reminiscent of the church on Fisherman’s Bastion in Budapest although not quite as grand.

The steeple with its multicoloured ceramic tiles is particularly gorgeous.

We”re not really sure why the statue of Svetozar Miletić, a Serbian lawyer, journalist, author, and politician who served as the mayor of Novi Sad in 1861/62 and 1867/68 seems to be throwing something (a crumpled ball of paper?) in the direction of the church.

Across the Square from Saint Mary’s is the old City Hall…

…flanked on one side of the square by gorgeous pale pink carved buildings that hold a Hungarian bank, a cinema and a hotel and shops.

Similar to what we have seen in other countries, some of the buildings here still have evidence of cannonball and/or bullet damage. We also had the chance to explore a bit of the area off the commercial pedestrian mall.

We headed to the former Jewish quarter, which is now called Theatre Square. The entire side of the street where the huge theatre is now situated used to be the second half of the street containing Jewish shops, homes and businesses. The theatre is very, very modern, reminding me almost of the Agha Khan museum in Toronto.

90% of Novi Sad’s pre-World War II Jewish population was sent to Auschwitz just six months before the end of the war.

Until then they had at least survived, if not under great conditions, through the Hungarian occupation. Only about 500 Jews live here now. There was never a Jewish ghetto per se in Novi Sad. There seemed to be recognition of the fact that the Jewish population helped build the city, and seemed until WWII to be fully integrated. The synagogue is the fifth on this site.

The concert at the synagogue was another exclusive Viking experience. The synagogue has become a cultural centre; the Jews here generally worship in a smaller space in the seniors’ residence adjacent to the synagogue.

On our way back to the ship we walked over a section of sidewalk tiles designed to mimic the foundation of an Armenian Church that once stood here. Near it is a 20th century monument to the pilots who brought supplies to Armenia during a crisis in that country.

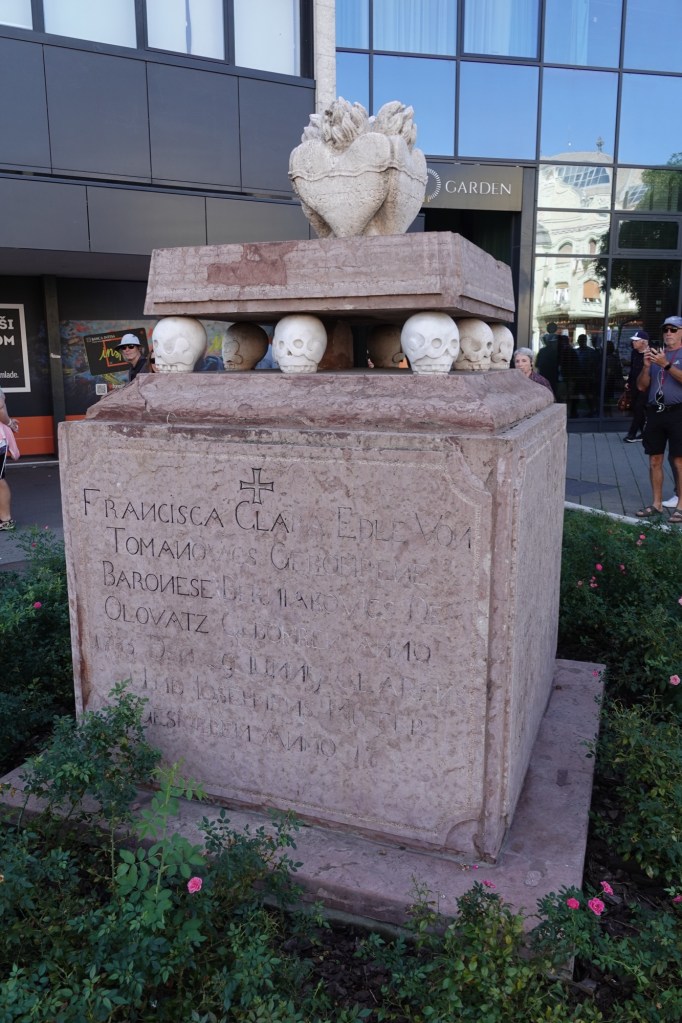

An adjacent slightly creepy monument with skulls is an Armenian tomb that was on this original site.

The government building of northern Serbia built in 1939 was intentionally constructed to look like a Danube river boat. The exterior is made of Croatian marble from the Adriatic coast, inside there is Carrera marble from Italy.

The flags in front of the building are in typical Republican colours of red white and blue. The national flag has stripes and no symbols. The flag with three stars represents northern Serbia; our guide quipped that they are not Michelin stars.

We finished our tour by walking through the Danube Park back to the ship. We were reminded that it was only about 125 years ago that the swamps here were drained. In the centre of the park is a lake (apparently there wasn’t much choice given the high water table) and Sisi Island named after the last Habsburg Empress.

We were all enamoured of this bronze statue of Serbian poet and painter Đura Jakšić in the park. From the shiny gold areas, it’s obvious that people think rubbing it brings luck.

We’d heard as we left Belgrade yesterday that there was a military parade scheduled for today. I was very curious as to whether it had been a long time in the planning, or was intended as an intimidation tactic to discourage the student anti-government protests that have been going on since November. Our lecturer/historian last night shared a video about the protests, where students reiterated that they are not partisan, but they’ve had enough of government corruption, and want a new election called now instead of in 2027 when it must, constitutionally, be held . Basically, it’s a non-confidence vote by Serbia’s young voters.

Despite being directed not to spend too much time on politics, our guide, Miroslav, was quite willing to tell me about the reasons behind the latest student protests taking place in the capital city, Belgrade. Last November, there was a train station roof collapse in Novi Sad that killed 16 people. The collapse was due to shoddy materials and workmanship that were the direct result of government corruption and a long trail of bribes and contractor kickbacks. For a Canadian, the parallels to things like substandard concrete in Montreal’s bridges was pretty obvious.

Not to be discouraged, Novi Sad’s mayor, who is somewhat universally reviled, has another project underway to create underground parking in the city. Unfortunately, this city which used to be swamp has a very high water table. Miroslav joked that the underground parking would only be suitable for submarines.

We reached the ship just in time for a light lunch. Ted stayed on board, and I headed off to a demonstration of the preparation of Serbian style poppyseed “strudel”.

Our small group travelled about 20 minutes by bus to Brkin Salaş.

Salaş is a uniquely northern Serbian word that describes a multi-purpose landholding with a farmhouse at its centre. The name of this salaş translates to “Moustache Farm” after the original 1904 Kosovan owner.

We were welcomed with a shot each of nettle and pear rakia in “dancing glasses”. The unique shape of the glass means that a dancer can hang onto it securely. The rakia is meant to be downed in a single shot.

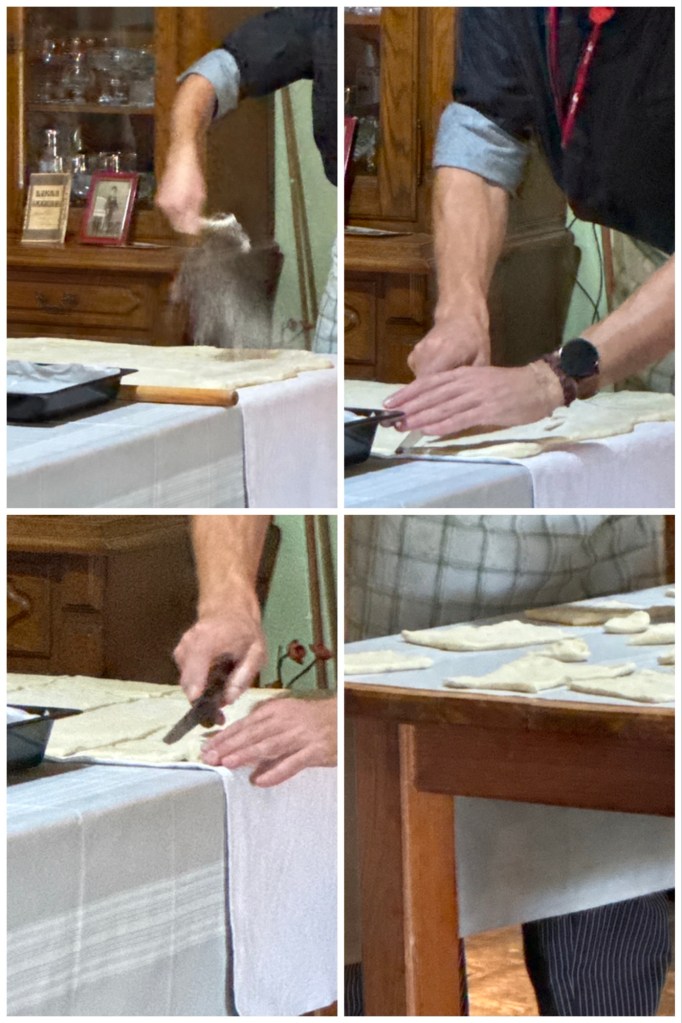

Then we got right into the strudel-making, demonstrated by the grandson of the current owner.

As we followed along watching him make the dough, he gave us hints for making the perfect dough:

- the milk for the yeast must be lukewarm

- use fresh yeast, not powdered, for the best results, and break it up but don’t crumble it – the broken up yeast bits will grow; wait until they’re bubbly

- only once the yeast is activated add the flour and salt

- use all purpose unbleached CAKE flour, which creates the tender crumb you want

- go easy on adding the flour, since you can add more flour more easily than adding more liquid

- mix by hand of wooden spoon. An electric mixer generstes heat, which kills yeast

- lard has the perfect amount of water in it. Substitute Crisco 1:1, but in order to use butter, melt it, add a couple of tablespoons of milk, and re-solidify it in the fridge. Substituting oil makes the dough too dry.

- the same dough WITHOUT the shortening component is perfect for deep-fried doughnuts

- you can halve the recipe, but not less, and don’t double it – doubling the recipe makes it too hard to knead.

Despite what the recipe indicates, he used no measuring tools of any kind beyond his intuition!

My big issue with yeast dough has always been the kneading. Miloş demonstrated a couple of techniques that would be good alternatives to my grandmother’s wooden spoon method.

Once he had a sticky dough that could be picked up, he kneaded in the lard until both the bowl and his hands ended up clean! The sticky dough changed texture to smooth yet soft. He cautioned that you don’t want to tear the dough during kneading, because that will also make it dry.

We each got a piece of dough in order to feel the texture. It was slightly warm, stretchy, and pillowy soft the way I remember my grandmother’s sweet dough feeling.

Then it was time to let the dough rise around 30 minutes in the sunshine, until doubled. Today’s 30°C/85°F outdoor temperature created the perfect natural proofing drawer!

While the dough rose, we were served local goats milk cheese, strips of pale yellow Hungarian peppers, and cheese-stuffed prunes wrapped in crisped fatty bacon strips!

There was also time to hear the story of how the current family inherited the house and land from the original owner, and the work they have put into creating a very small agroturism destination, supported by companies like Viking.

The farm now offers a restaurant experience by 24-48 hour reservation only (no walk-ins) in addition to cooking classes. Our young host and his fiancée keep their grandparents’ recipes alive.

Once the dough had doubled, Miloş floured a cloth work surface on which he used a long wooden dowel to roll the dough to about 1/4” thick. at this point, he would normally just make 2 large strudels, but for us he cut the dough into squares of about 4” x 4” so that we coukd make mini rolls.

He cautioned us to spread filling only on 2/3 of the square, and then roll beginning at the filled edge and ending with the “naked” edge. We were told not to spread the filling too thickly, but later on Ted and I both agreed that more filling was needed.

I’ve been under the misconception that I needed a specific kind of poppyseed grinder. Miloş assured me that a blade style coffee grinder or a mortar and pestle or even a pepper mill will work just fine.

It was now our turn to fill and roll our own strudels, and decorate them so they could be identified after baking.

Since everyone was anxious to explore the garden I was left behind to egg-wash everyone’s creations.

We visited with the dogs, rabbits, guinea pigs, and chickens in the garden while the strudels baked.

And then… there they were!

The final poppyseed “strudel” was almost exactly like my grandmother’s yeast dough poppyseed roll. She would not have called it strudel, because to her that meant the flaky pastry baked goods similar to this morning’s breakfast (and also not like Austrian strudel), but really the name is not important.

They were delicious.

I had good reason to skip dinner. Instead there was late evening cappuccino and city lights.