This morning’s start: spinach and cheese “pie” with salted Balkan yogurt and chives.

Our world cruise friends Joseph and Anthony just completed a river cruise from Amsterdam to Bucharest, although not with Viking. Joseph shared lots of photos and insights in Facebook that have lent extra perspective to some of the places our itineraries had in common.

One of Joseph’s posts included information from one of their onboard lectures: “Tito broke with Stalin in 1948, making Yugoslavia one of the few communist countries not under Moscow’s control. He charted his own communist path, mixing a planned economy with some market elements like foreign investments and allowing entrepreneurial activities by his people. They were also allowed to travel outside the country. But Tito was a true dictator. He crushed opposition, banned dissent, and used secret police to imprison or eliminate critics. Political pluralism was nonexistent.”

The comment about allowed travel struck me, because of all the stories I’ve heard from my friend Josie who was unintentionally trapped in Tito’s Yugoslavia when she was a child. Her Canadian immigrant family had temporarily gone back, and were not allowed to leave. She has harrowing tales of family members being taken in for “questioning”, and neighbours being encouraged to report on each other’s “unpatriotic” activities.

Thinking about Tito was particularly relevant today, given that our afternoon tour will take us to the palace he commandeered as his residence.

But first, another panoramic tour to experience a couple of the highlights of another fascinating Eastern European city.

The Serbian capital of Belgrade is sometimes referred to as Europe’s most resilient city; despite being ravaged and rebuilt 20 times in its history, many of the city’s finest buildings have been gloriously restored.

It’s interesting that almost half of Serbia’s 6.5 million people live in metropolitan Belgrade, yet there’s nowhere near the pedestrian or vehicular traffic we’d associate with a North American city of that size. That said, rush hour drivers are aggressive and fearless! I was glad to be in the capable hands of professional coach drivers.

We started our morning tour with a guided walk around the famed Kalemegdan Fortress. Its name translates to “field and forest”, and the park, redesigned with walking paths in the Central European style during the country’s Habsburg period, certainly lives up to its name.

The dominant types of trees in the park are linden and horse chestnut, visible all around the statues that punctuate the grounds. The dominant native conifer tree is a the yew with red berries.

The large monument in front of the fortress depicts the goddess Nike on a white pedestal. It was erected the period between the 2 world wars in gratitude to France in. In WWI, when Serbia was attacked from both sides by German allied troops (Austro-Hungarian, German, and Bulgarian) France sent naval ships to rescue Serbian soldiers and take them to the Greek islands to recuperate. Those soldiers, along with French military, were then able to return to Serbia and win back their territory.

The fortress dates to Ottoman times. After the liberation from the Turks, under the rule of Prince Michael, the fort was turned over to the Serbian kingdom. Its walls loom over the Old Town.

The fortress is now surrounded by tennis courts, basketball courts, and a children’s playground! Inside the main gates of the fort is a Serbian exhibition of animatronic dinosaurs.

We entered the central part of the Fortress through the Istanbul Gate along what is called the Istanbul Road.

All the doors of the gates of the Belgrade Fortress were made out of wood reinforced with wrought iron. The doors still show evidence of the Serbian insurrection against the Turks, in the form of bullet holes through the iron.

In the moat is the permanent exhibition of the history of Serbia’s military.

In the centre of the Fortress is a 7 ton cannon original to the late 19th century.

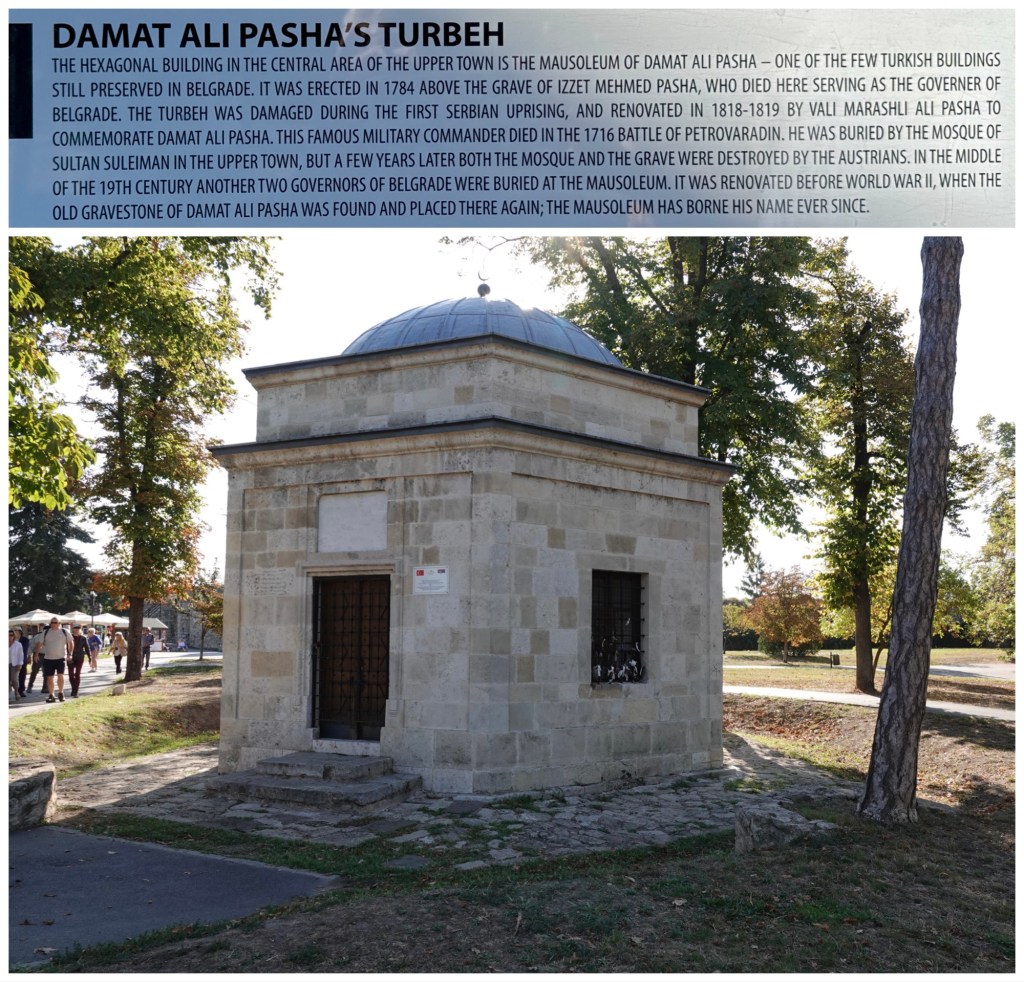

The hexagonal stone tomb in the centre of the Fortress, with the crescent moon on top, is the tomb of an Ottoman Governor.

From the top of the fortress, we got a fabulous view of Belgrade and the waterfront along the confluence of the Sava and Danube Rivers. It was obvious why the Ottoman fortress was built on this hill.

The tall monument of a nude man overlooking the river dates to the 10th anniversary of victory in WWI, which was when the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was created. His sword pointing downward represents victory in World War I; the hawk in his other hand symbolizes pride.

Conservative elements of Yugoslavian society at the time when the statue was created objected to a nude male body being displayed in the centre of the city. They insisted that it be moved to the furthest point away from the city’s center, and to face out toward the river (toward an area at that time uninhabited Swamp land, but is now the newest part of Belgrade, created during Tito‘s time) so that the statue’s genitals would not face toward the city. From our vantage point within the Fortress, we only got to see the statue’s cute chiselled butt.

En route back to the ship, Ted was able to get a photo of the front of the statue, showing the hawk in the man’s hand.

After the fortress we walked to the pedestrian zone on Prince Michael Street, named after the ruler at the time of the defeat of the Ottomans. After Prince Michael led the troops that liberated Belgrade from the Ottomans, the city was reconstructed in the late 18th century Habsburg architectural style, making the city’s buildings look like those of Vienna and Prague.

The Building of the Patriarchate is the administrative seat of the Serbian Orthodox Church and its head, the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Finished in 1935, the building was declared a cultural monument in 1984.

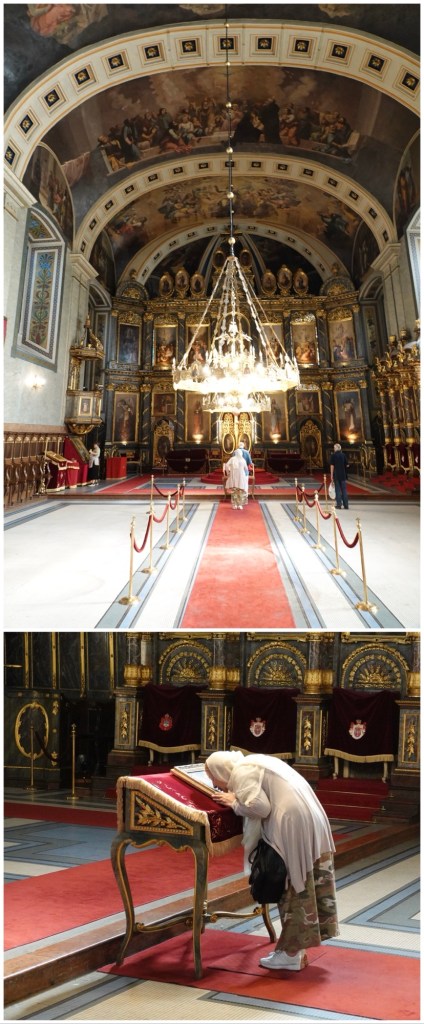

Ted and I chose to walk to the Serbian Orthodox Church dedicated to archangels Michael and Gabriel. Unlike the other churches we’ve visited, this one was decorated and painted in a slightly more western style, because it dates to the time when predominantly Austro-Hungarian (Habsburg) artisans were employed in the city.

We were fascinated not only by the worshippers “venerating” the icons by putting their foreheads on them, or even kissing them, but also by the woman whose job it seemed to be to do a never ending circuit around the church windexing the glass covers over the icons to remove forehead and lip marks.

After our free time strolling, we reboarded our bus and drove past the Belgrade waterfront compound project started by a company from Dubai in 2014 who have already invested 5 BILLION USD. Because the properties are unaffordable for Serbians, foreigners bought in as investments. Covid interrupted construction, and it is still not complete. Sadly, the development’s location required the shutdown of the gorgeous main railway station with its incredible 60 ton monument of King Vukan Nemanjić standing on a broken Byzantine helmet.

Our guide pointed out a building still in ruins that was Yugoslavia’s ministry of defence, bombed during the Kosovo Crisis in April 1989 by NATO pilots.

Basketball is almost as popular as soccer here, as evidenced by the street art.

We drove through the Dedinje Park neighbourhood, which is the wealthiest in Belgrade and is home to the compound containing Tito’s mausoleum. Tito separated Yugoslavia from Russia/Stalin after just 3 years of alliance after WWII, establishing a “soft” version of communism nicknamed “CocaCola Communism” that allowed western fashion and influences. How “soft” it was is probably dependent upon who is asked.

Our second tour stop was to visit Belgrade’s most famous church, which is also one of the largest Orthodox churches in the world. On our walk to it we passed the monument to “Black George”, a hero of the early 1800s uprisings against the Ottomans.

Saint Sava was a canonized Serbian crown prince who renounced his crown to become a monk, became the city’s patron saint, the first Serbian archbishop, and the founder of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Construction of the church dedicated to him was begun in 1935, interrupted by WWII and communism, and finally completed in the late 1980s. The church is on the site where Sava’s relics were burned by the Turks in retaliation for a 15th century uprising by the Serbs.

In the period during which the church building was incomplete, a much much smaller church was built in just 70 days in 1935. It is still used as a place of worship.

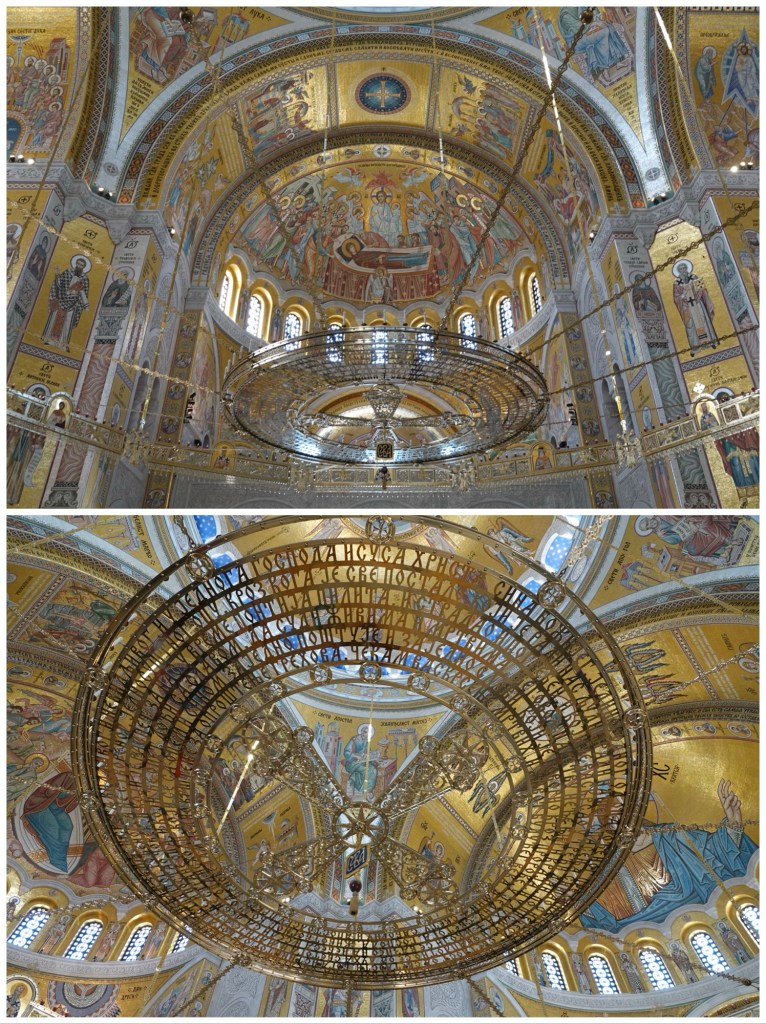

The big church’s main dome, weighing 4000 tons, was completed in 1989. To put the size of this church into perspective, the dome is larger than that of the Hagia Sophia.

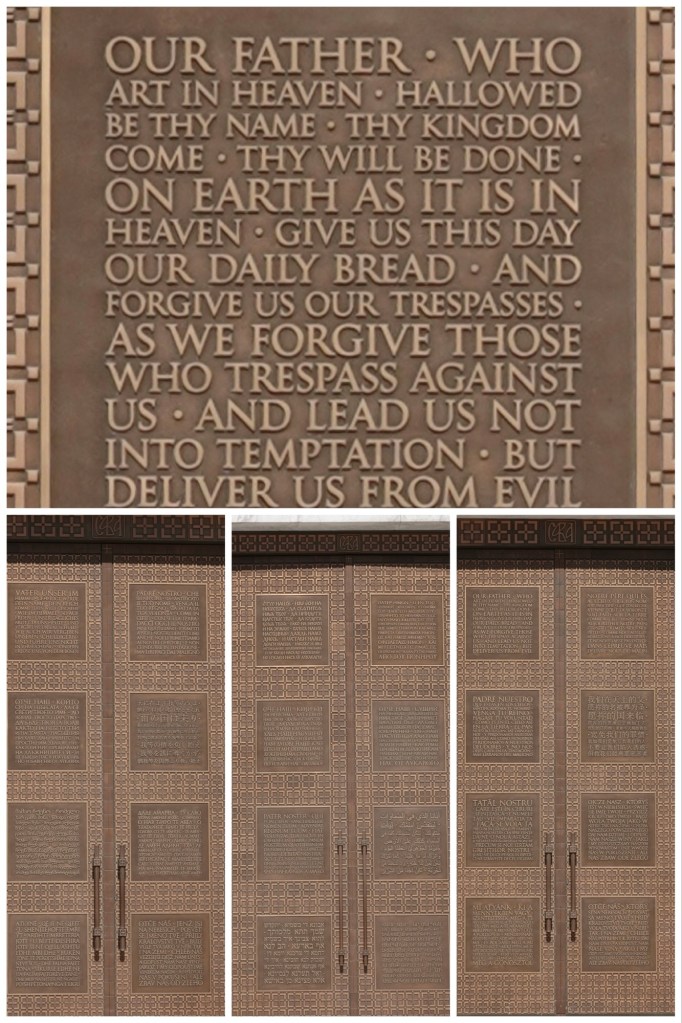

Each set of exterior entry doors had a specific prayer inscribed on it in 24 languages. One entrance has the Lord‘s prayer, one has a prayer to holy Mary, and the third has a prayer called “Oh my Lord”, that is specific to the orthodox religion.

Above the doors were mosaics depicting Jesus, flanked by Saint Sava and Saint Simeon.

Photos really do not do justice to the gorgeous white Serbian and Italian Carrera marble, the sheen of the green marble interior columns, and the glowing golden mosaics, which absolutely glitter in the light – but Ted certainly tried.

It is quite amazing that all the mosaics in the church were created in only four years, between 2013 and 2017. The technique used to make them sparkle the way they do is called sandwiched glass. A layer of glass is spread with the gold background tiles, covered with another layer of glass, and then the coloured portions of the mosaic created.

In all orthodox Christian churches, there are very strict rules about the fact that the altar must always face east toward Jerusalem. Additionally, between the main part of the church where the congregation stands and the altar itself there is a wall with icons that has three doors. The central door is exclusively reserved for priests to enter and exit; that door is referred to as the royal door. The two lateral doors can be used by other clergy or laity who need to enter the altar area. As is typical of Orthodox churches, there are no pews. The congregation stands throughout the entire Sunday liturgy, which takes about one hour and 45 minutes.

The main motive in the central dome is of the ascension of Christ. He is surrounded first by four angels, and then by 15 figures comprised of the 12 apostles plus Mary, Joseph, and John the Baptist.

Specific to Serbian Orthodox churches, the chandeliers are shaped like a royal crown turned upside down, symbolizing mourning for the lost kingdom. In the central part of this church’s chandelier is the Apostolic Creed in Cyrillic.

The church had three separate choir balconies. In an orthodox service, there is no instrumental music, only the voices of a human choir. The priest will also chant a portion of the service.

From Saint Sava we headed back to the ship for lunch and a quick break before our afternoon tour, which I’ve separated into a separate episode so as not to overwhelm our memories with too many stunning photos in one entry when we look back at this day..