This is the highlight of the “cruising” portion our trip: passing through the stretch of the Danube that is known as The Iron Gate.

But first, breakfast. now that we’re headed for Serbia, the flaky pastry is no longer called banitsa. Now it is “burek”, and today’s was wild mushroom.

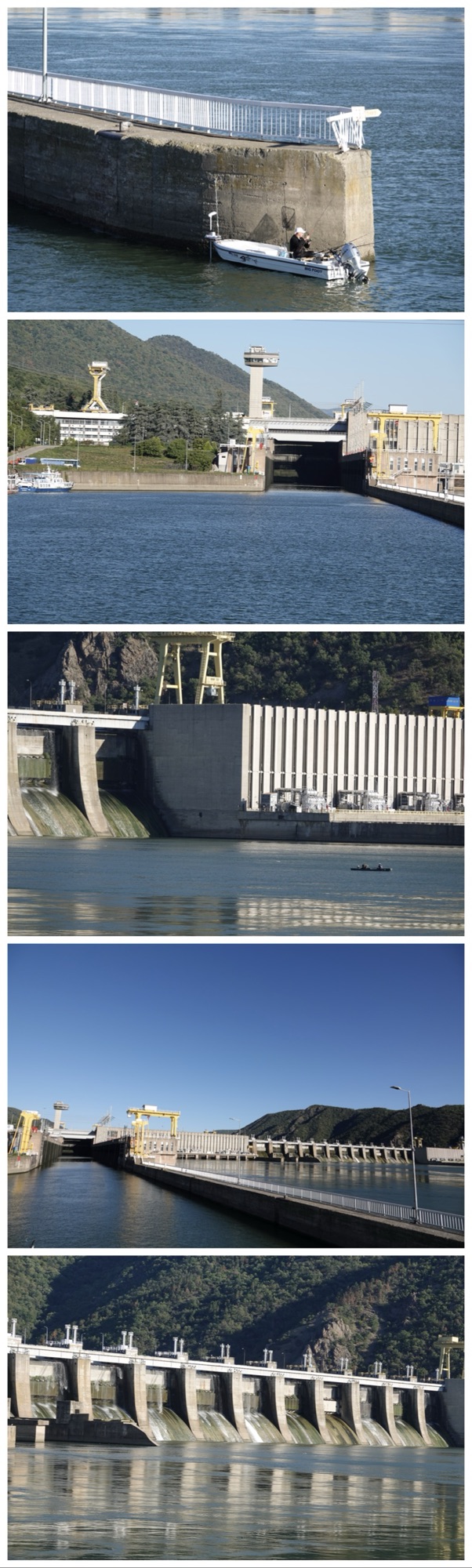

“Iron Gate” is the name of the gorge on the Danube that forms part of the boundary between Serbia to the south and Romania to the north, but to most people it simply refers to the last barrier along this route, just beyond the Romanian city of Orșova, that contains two hydroelectric dams, with two power stations, Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station and Iron Gate II Hydroelectric Power Station.

There is no actual “Iron Gate”, but given what a challenge this gorge was for the Romans and Ottomans to traverse, it must have seemed as daunting as trying to get through a locked gate of iron, and early cultures referred to it by a similar name (“Demir-kapija” in Turkish translates to iron gate).

Our Program Director, Paul Evans, narrated us through the journey

The Danube here is starting to look a bit more familiar: steeply sloping verdant banks, and red-roofed houses.

We passed through the lock at Iron Gate Two dam and hydroelectric station around midnight last night, which we slept through.

We got to Iron Gate One around 8:20 a.m. This is the biggest lock on the Danube. Located at km 943 of the Danube (km 0 being at Constanța, Romania), it moves ships 45 metres vertically. It took only about 1 hour in total rising to the higher level inside the double-chambered Serbian lock, which was built beginning in 1965 and opened in 1972, but has been renovated more recently than the adjacent Romanian lock.

Interestingly, unlike going through the Panama or Suez canals, there is no fee for ships traversing the Danube locks.

As we passed out of the Iron Gate One locks, on the Serbian side of the river we saw a Tito sign above the former Yugoslavian flag. There are not a lot of those still on display!

The rest of the morning was “scenic sailing” along what is arguably the most beautiful stretch of the Danube – after the UNESCO designated Wachau Valley stretch, of course. With the sun glinting off the waters, it certainly was gorgeous.

Romania’s Statue of Liberty, visible from the river, celebrating post-communist freedom, is called simply “Danube”.

The river-side monument to Koča Andjelkovic, one of the prominent figures of the Serbian history of the 18th century, revered as a man who, thanks to his courage and military abilities, became the leader of Serb volunteers in the fight for the liberation from the Ottomans.

The three best-known highlights of cruising the Iron Gate were in their full glory today:

(1) The ancient Roman Tabula Traiana, an inscription carved by Emperor Trajan’s troops into the rock wall in the Djerdap Gorge, the least accessible spot of the Roman road that the Emperor and his warriors travelled in their campaign against the Dacians.

(2) The impressive 55m tall rock sculpture Statue of King Decebal, the last Dacian king, the carving of which was inspired by Mount Rushmore.

Very near King Decebal’s face we passed the Mraconia (“secret place”) Monastery in the narrowest part of the Danube, where it is just 150m (approx 490 ft) wide. It is also at its deepest here, up to 50m deep. Here the Danube flows between the Carpathian and Balkan mountain ranges.

(3) The Golubac Fortress, which we didn’t actually pass until around 10 p.m. as we were exiting the Iron Gate stretch of the river, by which time it was spectacularly lit.

We had a passport process to do before stepping onto dry land, since Serbia is neither EU nor Schengen. That meant a THIRD stamp (the first when we entered the Schengen Zone in Amsterdam, the second in Vidin Bulgaria) in our new passports!

And then we were on shore in Serbia.

For the first half of my life, there was a country called Yugoslavia. Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia didn’t exist. I had no real concept that those three countries, along with Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, and Montenegro, were at one time completely different nations.

Of course, as a child I also thought that Tito’s first name was “Marshal”.

Yugoslavia existed from 1918 to 1992, coming into existence as a union of Slavic nations after WWI, following centuries of foreign rule by the Ottomans and then the Habsburg dynasty. It was invaded by the Axis powers in 1941, and then at the end of WWII a council appointed by the King called a parliamentary election that established the Constituent Assembly of Yugoslavia, which on 29 November 1945 proclaimed Yugoslavia a federal republic, abolishing the monarchy. This marked the beginning of a four-decade long uncontested communist party rule of the newly proclaimed Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia.

From 1944, long before I was born, until his death in 1980 leader Josip Broz Tito (the “Marshal Tito” of my childhood) ruled the country .

By his force of will – and just plain force – the various cultures and ethnicities were held together. After his death, and the revolutions of 1989 (concurrent with Romania’s overthrow of Ceauşescu), Yugoslavia broke up almost into its pre WWI borders.

Today we’re visiting Serbia for the very first time.

Once again we chose just the included walking tour, described as: Experience Everyday Life in a Small Serbian Town. Donji Mikanovac certainly qualifies, with a population of just 1500.

Set along the banks of the Danube River, the history of Donji Milanovac is an intriguing one; since its founding, the town has been relocated three times because of persistent flooding, and then intentionally flooded during the construction of the Iron Gate dam, hydrelectric plant, and locks.

The mastodon that has become the town’s symbol was actually left over from an art competition held in the 1970s.

Close to the waterfront is the town’s WWII cenotaph.

Despite its small size, the town is actively pursuing tourism. To that end, there are handicraft kiosks on the dock, gardens, parkland, and a fairly new fountain in the town’s only roundabout.

Although there was also a Uniworld river cruise ship docked here today, there was no one else in town. Our guide told us (unprompted) that only Viking offer walking tours in town (and pay local guides, donate to the choir, and support the local school with English language resources for their library and teachers). Other cruise lines dock and then offer only the kind of optional excursions we also could have chosen: visiting the archeological site at Lepenski Vir or hiking the national park.

Many of the taller buildings in town are festooned with banners or murals highlighting important people and events in the town’s history, with both Serbian and English captions.

We visited the Serbian Orthodox Church dedicated to Saint Nikola. The original church was built in 1840, but all that remains of that church – which is now under the Danube in the original town – are two frescoes in the front entrance.

Interestingly, while the churches in Romania and Bucharest were always referred to as Eastern Orthodox, our guide here specified “Serbian” Orthodox. There’s actually no separate religious doctrine involved, but the Serbian Orthodox Church, like other national Orthodox churches, has its own unique cultural traditions and practices, such as Slava (the celebration of a unique “family” patron saint).

The new church was consecrated in 1973. Its interior is adorned with beautiful paintings and icons, many of which were created using laser painting processes, which are much faster and less expensive than hand painting with organic paints on wood or wet plaster.

The ornate light fixtures also had icons on medallions in their design, and there were beautifully woven textiles hanging at the sides of the church.

The priest welcomed us to the church before we were introduced to the Choir of the Holy Trinity church of Negotin, conducted by Professor Svetlana Kravenko. The nine voice choir filled the space with glorious sound.

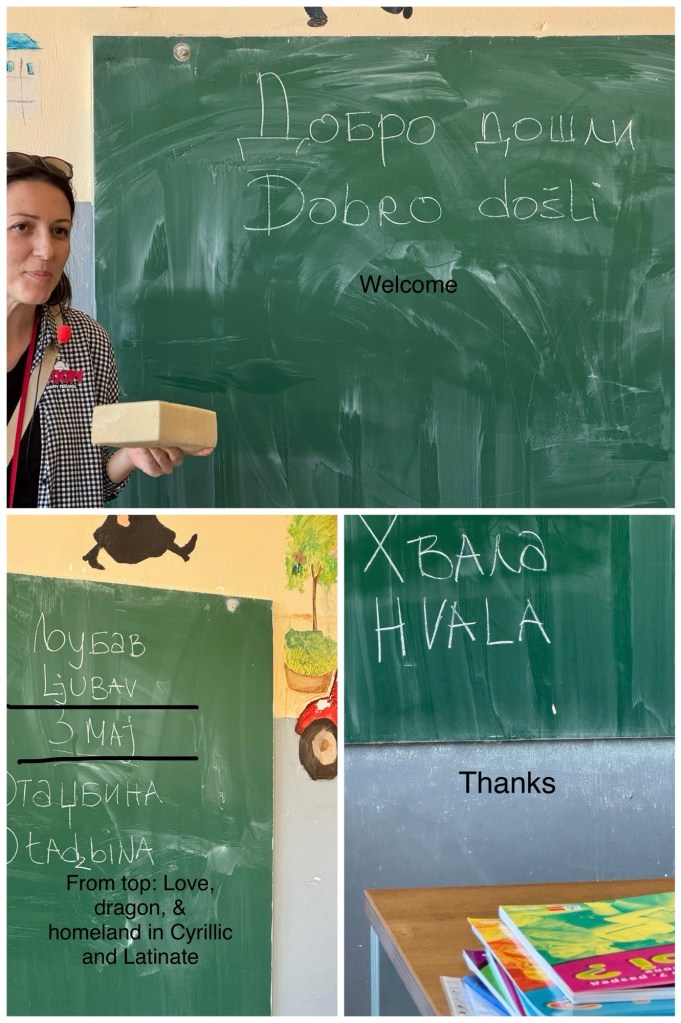

After leaving the church, we visited the town’s only elementary school. The approximately 300 elementary school aged students attend school in two shifts, the younger students from 8 until 1, plus lunch and childcare until 3, and the older students from 4 until 7 p.m. Although there is a secondary school in a town about 90 minutes away by bus, most parents choose to send their children to Belgrade at age 15 to attend secondary school as boarding students.

We got to sit in a classroom and learn a little Cyrillic, Serbia’s official script, from our guide.

It was only a 90 minute excursion, but gave us an interesting introduction to small town Serbia.

Tonight’s dinner was a special “Taste of the Balkans” event, with our wonderful wait staff decked out in Balkan dress!

The meal was kicked off with a shot of Serbian honey brandy.

Wine, of course: Moft Cuvée Alb, a white wine from Murfatlar, Romania, made from a blend of Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, and Muscat Ottonel grapes.

Then a delicious oyster mushroom soup with paprika and sour cream.

Our main course: a Balkan platter with roast pork, roast chicken, garlic lamb kebabs, pork and rice filled cabbage rolls, potato wedges, grilled vegetables, and rice pilaf. Wow! That’s a LOT of food!

That was it for our day. Ted is still battling a cold that has him exhausted from lack of sleep, and we have an early start for a busy day in Belgrade tomorrow.