WARNING: This is a long post, and contains facts which may make people uncomfortable. Please keep in mind that this is a personal blog and not a travelogue; the things that I write about are things I think will be important first ME to be able to look back on.

My father’s family left their home in Poland just as WWII was ending.

The record of what I know about their exodus from Europe after World War II starts here: Episode 65. There’s a single episode interruption in the narrative at Episode 72, but it restarts at Episode 73.

It wasn’t a voluntary move; the Russians were advancing into the area, and my grandfather (who had been involuntarily in Russia twice in his life) had no interest in being overrun. My grandparents and their three unmarried children, of whom my dad at 15 was the youngest, fled from their farm holdings in Wilkow (Secymin) across the Vistula (“Weichsel” in German) River, ending up as “displaced persons” in Holtum-an-der-Geest Germany in the British Zone (Episode 73).

My dad’s sister, Lydia, ended up marrying the son of one of the local German families, almost all of whom had been compelled to take in the “DP”s. That, in a nutshell, is why I have cousins still living there.

One of the things that pleased me about son #2 wanting to come to Germany to find out more about his maternal grandfather (my dad) was that it would also give me the opportunity to – hopefully – fill in some of the gaps in what I knew about both my parents’ journeys across the Atlantic Ocean to Canada.

Ted and I visited Pier 21 in Halifax years ago, hoping that we might find passenger lists for the SS Beaverbrae, the ship that brought my mother, father, and grandmother – in that order, in different years – from Bremerhaven to Canada. Unfortunately, Canadian immigration records don’t get released for 75 years, unless the person to whom they refer is still alive to give permission to access them. For me, the earliest possible access dates for my mom’s records would be late 2024 (they haven’t been yet), for dad 2026, and for my grandmother 2027. I had high hopes that the German records would be accessible now. (Spoiler alert: they weren’t.)

My cousin Doris drove today, with part of the route along the autobahn. Son #2 sat in the front passenger seat, watching the speedometer.

Officially, Bremerhaven is “the city at the seaport of The Free Hanseatic City of Bremen”, which is a mouthful in either language, but for us today its big draw was the Deutsches Auswanderer Haus (the German Emigration Centre museum), which Ted and I chose not to visit back in 2022 (included in Episode 297), when we did other things instead here in the port city.

Our visit to the emigration museum turned out to be a very emotional one for both me and my cousin Helga. Each time we are together we realize how much alike we are.

At the entrance to the museum we were each handed an identity card. I particularly wanted to follow someone who had left from Germany via Bremerhaven (as opposed to Hamburg) after WWII. The others in our group had emigrants from the 18th, 19th, and earlier in the 20th century. We also got a swipe card to use to access audio guides throughout the museum – in both German and English.

We were taken into a waiting room, modelled after the one that existed here in the 1890s. On the wall, a notice from the police to beware of card sharks, thieves, pickpockets, and unsavoury strangers.

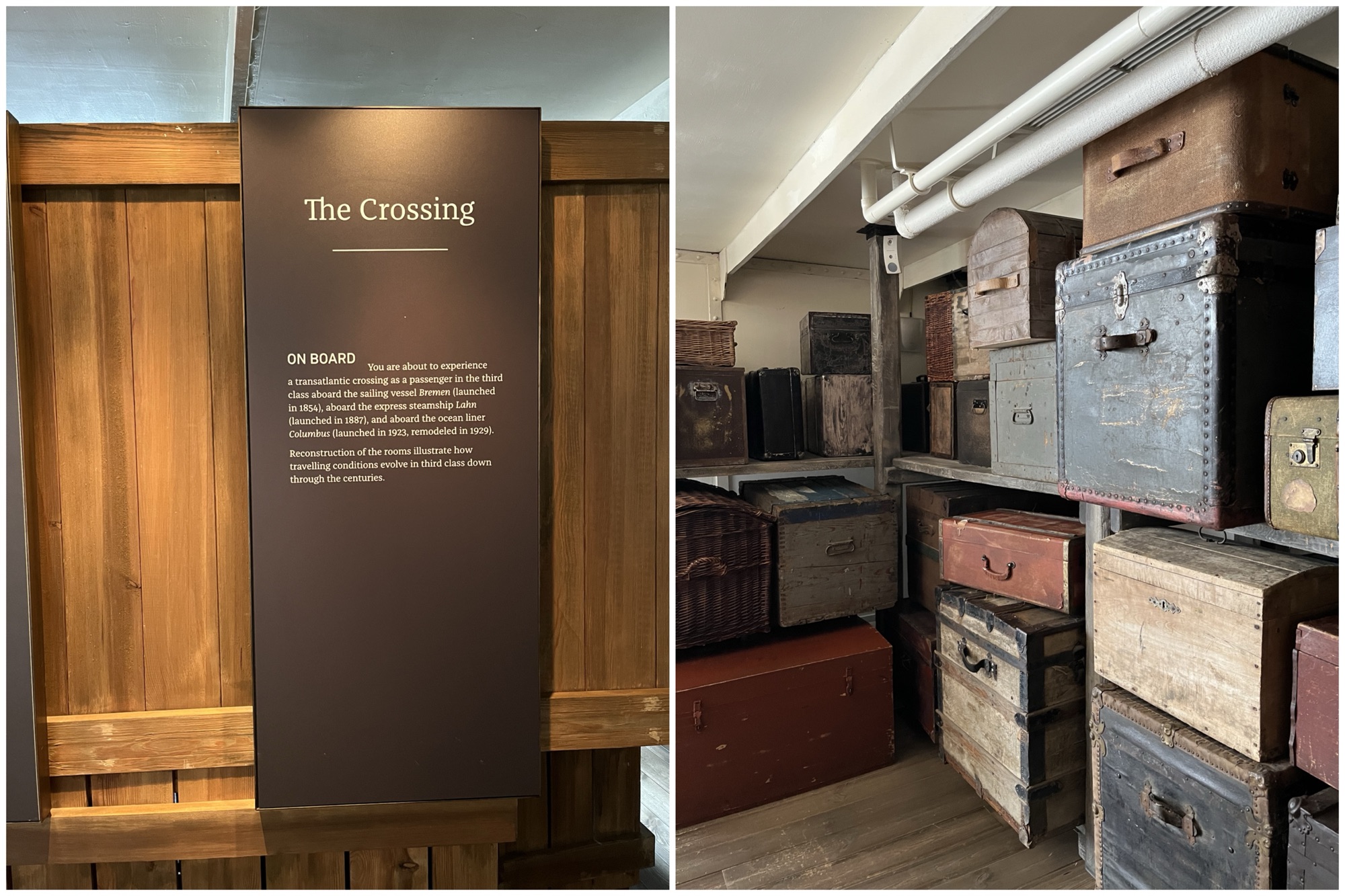

From there we proceeded to the dock, where we eventually headed up the gangway to our ship.

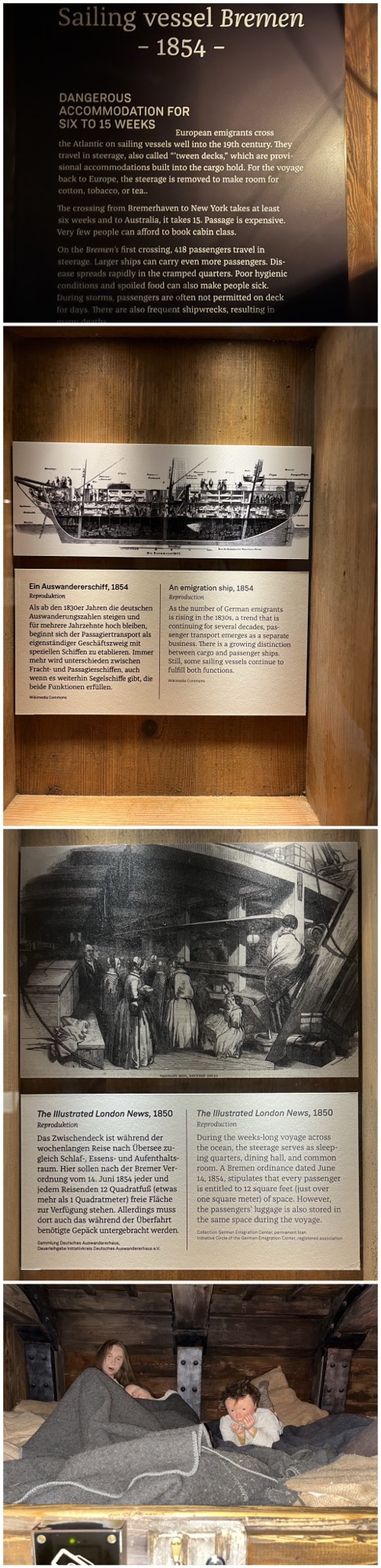

Displays compared the ships used in 1854, 1887, and 1923. My parents’ and grandparents’ journeys would most closely have matched third class on the 1923 ship.

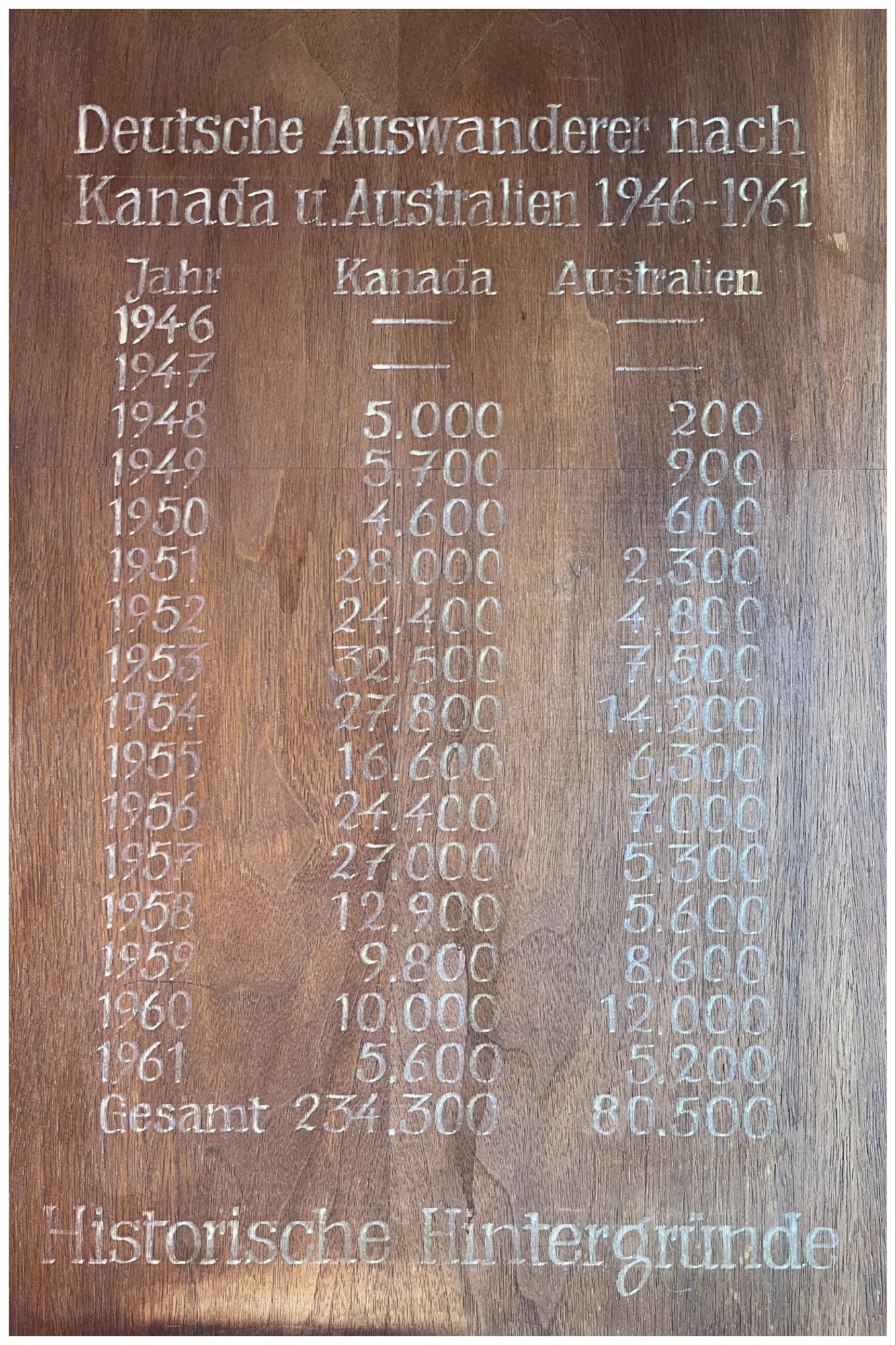

It was interesting to see the numbers of German emigrants accepted into Canada in the post-war years.

My mother was in the 1949 cohort, my dad in 1951, my maternal grandmother in 1952, and my maternal great-grandmother in 1954. My other relatives came either to the U.S. before 1900 or to Canada in the years between the two World Wars.

The Museum’s “journey” is in two parts: leaving Europe, and arriving in a new land.

There was not a lot of focus on the emigrants who ended up in places other than Ellis Island. Perhaps that is still to come.

Richard Morgner (my ID card) immigrated to the US – so far there are no Canadian immigrant stories available to follow. No matter, I have my own family’s experiences.

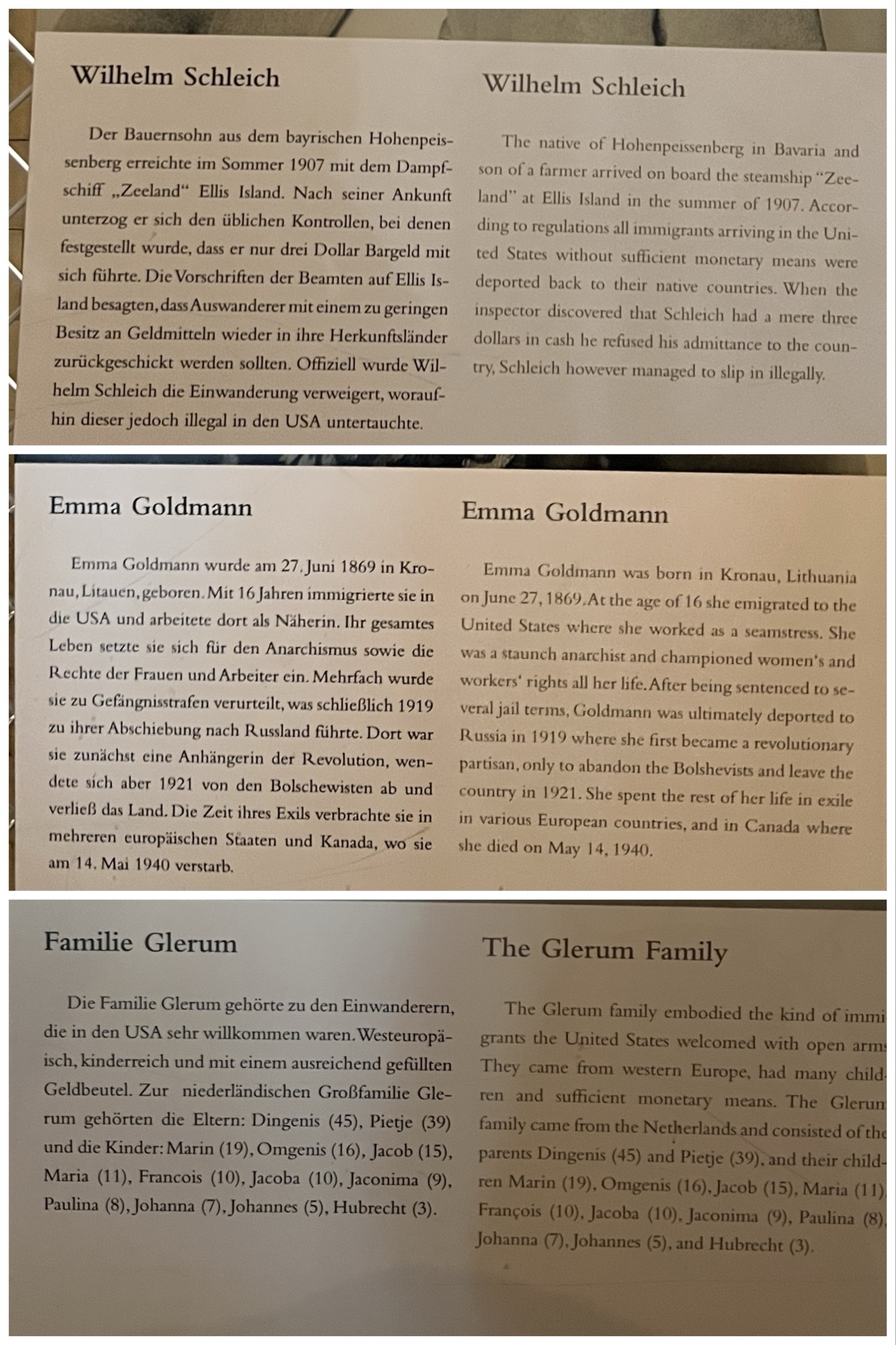

Ellis Island, also called the island of tears, was the largest immigrated station in the USA. In 1907, in the year with the highest number of female immigrants, around 1.25 million people passed through Ellis Island. In total, more than 12 million female emigrants were smuggled through between 1892 and 1954. Upon arrival in New York, 1st and second class passengers simply disembark after a fleeting inspection the ship. The United States assumes that these passengers have sufficient funds to avoid a burden to the state.

Third class passengers, on the other hand, are transported by ferries to Ellis Island. There is a medical examination in the Registry Room, the large hall. After that, an inspector at the Legal Desks asks them a series of 29 questions. If all their papers are in order and the state of their health is unremarkable, the inspection process on Ellis Island takes 3 to 5 hours.

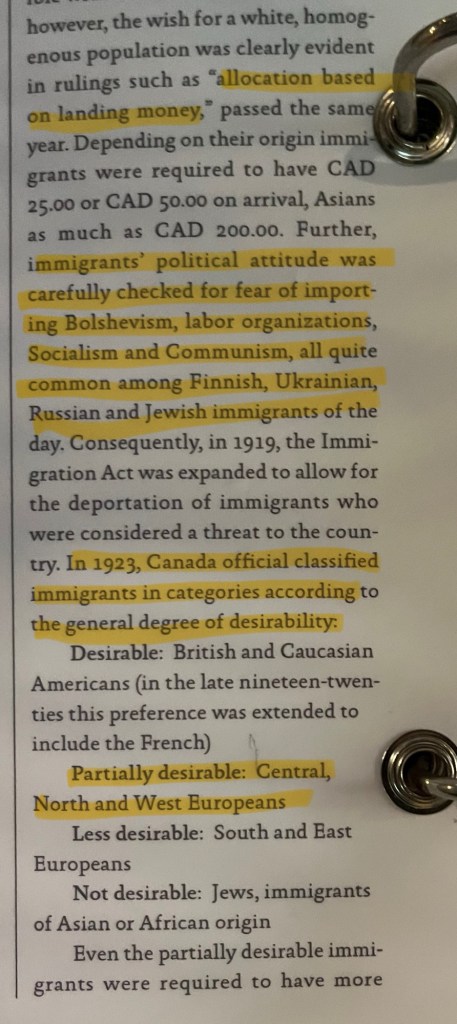

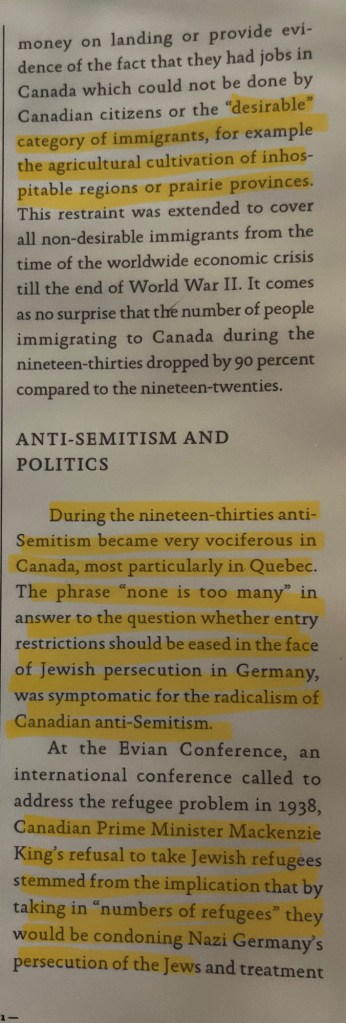

Outside the Ellis Island display were binders describing the immigration processes for other countries. I took pictures of the pages related to Canada. From today’s perspective, it’s not a pleasant story, but it is an important window into what made Canada the country it is today, and – I think – shows that we have learned and grown.

Immigration has never been an easy process.

From that point on in the exhibit, the focus was really on immigrants coming through New York’s Central Station, but it was interesting to see the poster depicting Canada to immigrants, as well as a comparison of immigration numbers.

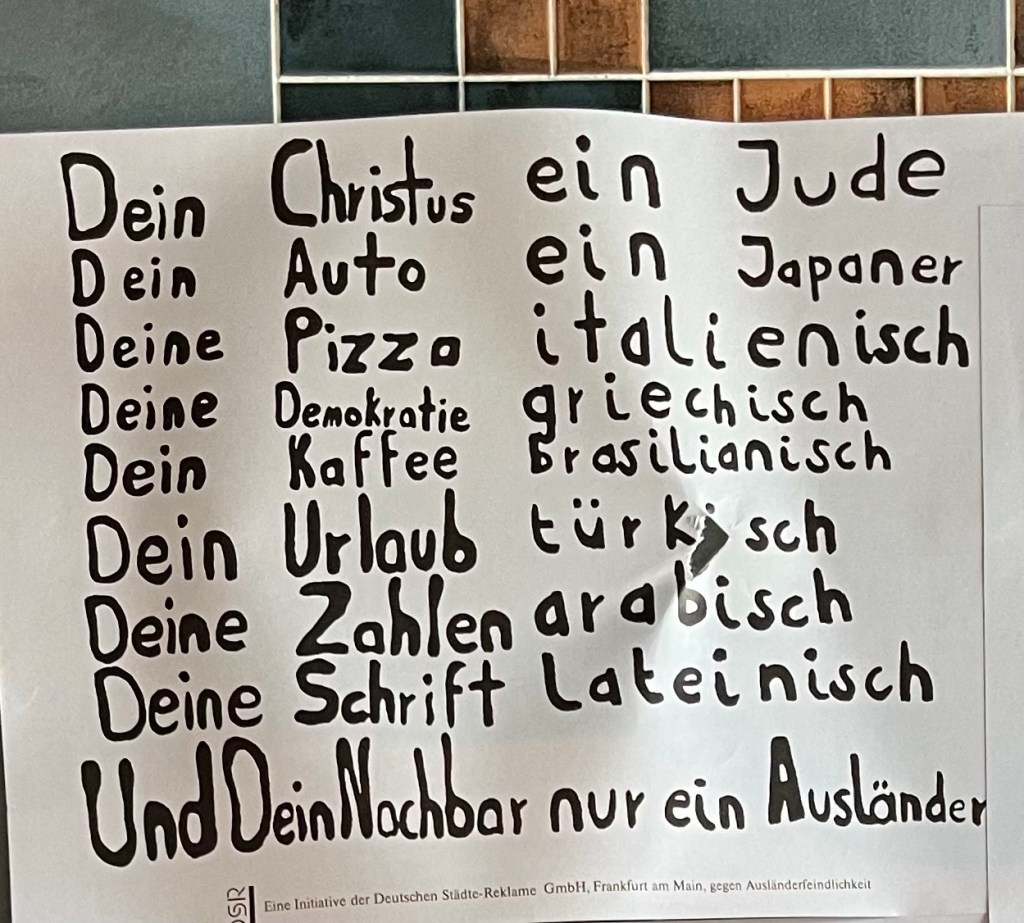

There were displays highlighting the accomplishments – and challenges – faced by large immigrant communities. It made it very easy to relate to present times; just substitute another country and continent fir “Germany” and “Europe”.

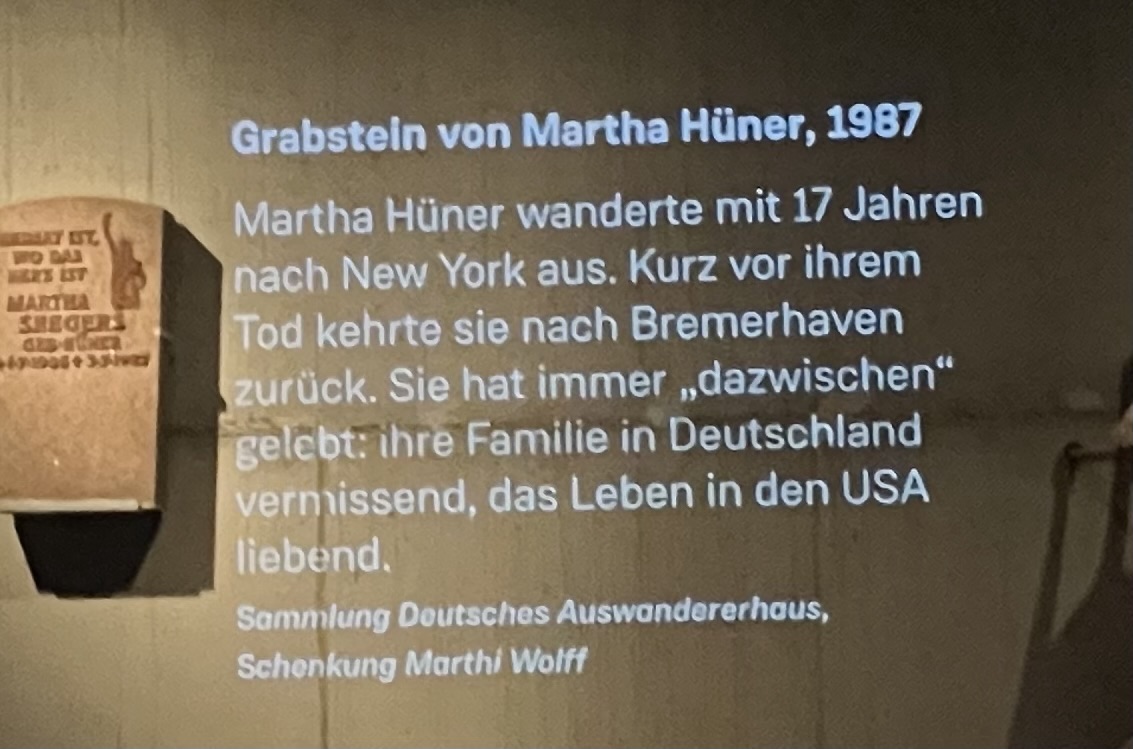

The words below could be almost universally applied to all immigrants: “in between”.

The Emigration Museum also includes a “Hall of Debates”, where via our swipe cards we could listen to four examples of how people with and without an immigration history in the Federal Republic of Germany have controversially discussed issues of whether, how, at what cost, and using what criteria countries should accept immigrants. Unfortunately, all the debates were only available (for now) in German.

Two posters near the end of the tour particularly affected me.

Outside the museum are the chilly port waters of Bremerhaven. Son #2 really wanted to put his feet in the water. Both my cousins reacted with “No! Terrible idea!” Instead, I took a picture of him BESIDE the water.

On our way “home”, we detoured past a place that I didn’t know existed, and that I wished never had: the Valentine’s Day Bunker.

Driving through what seems like any other small semi-rural German town, it is shocking to come upon a massive ugly concrete bunker, larger than most modern factories.

We were too late in the day for the guided tour, but Helga’s son Matthias, who had been here before, graciously acted as my tour guide, ensuring that I wouldn’t miss any of the important exhibition areas.

Built beginning in 1943 on formerly idyllic rural land along the Weser River that had been transformed beginning in 1938 into a huge Nazi military complex, the bunker was an engineering marvel and a human tragedy. Hundreds of acres of land were transformed into a fuel depot and factory complex in which the Nazis intended to construct state of the art submarines which could be launched directly into the river and from there into the North Atlantic.

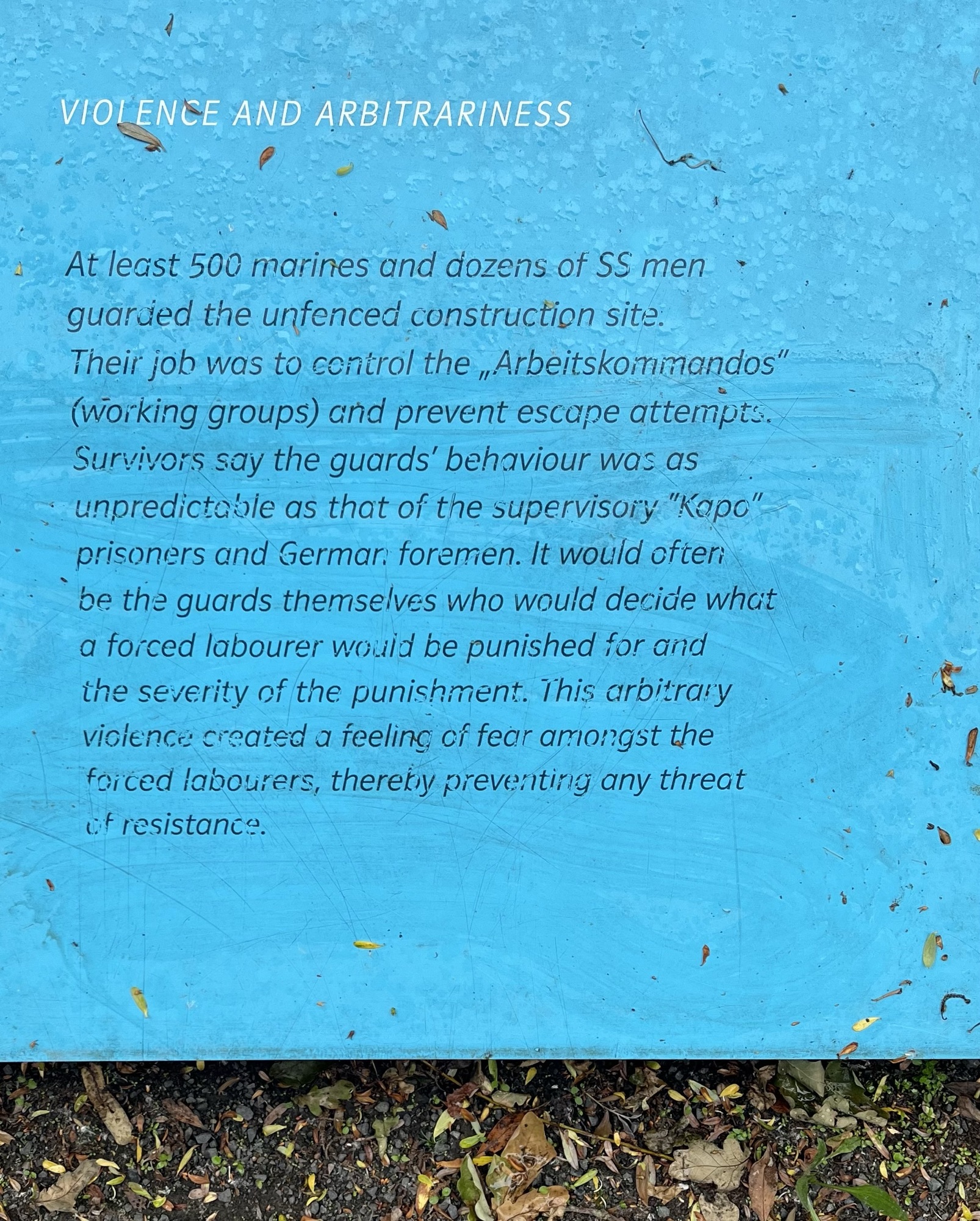

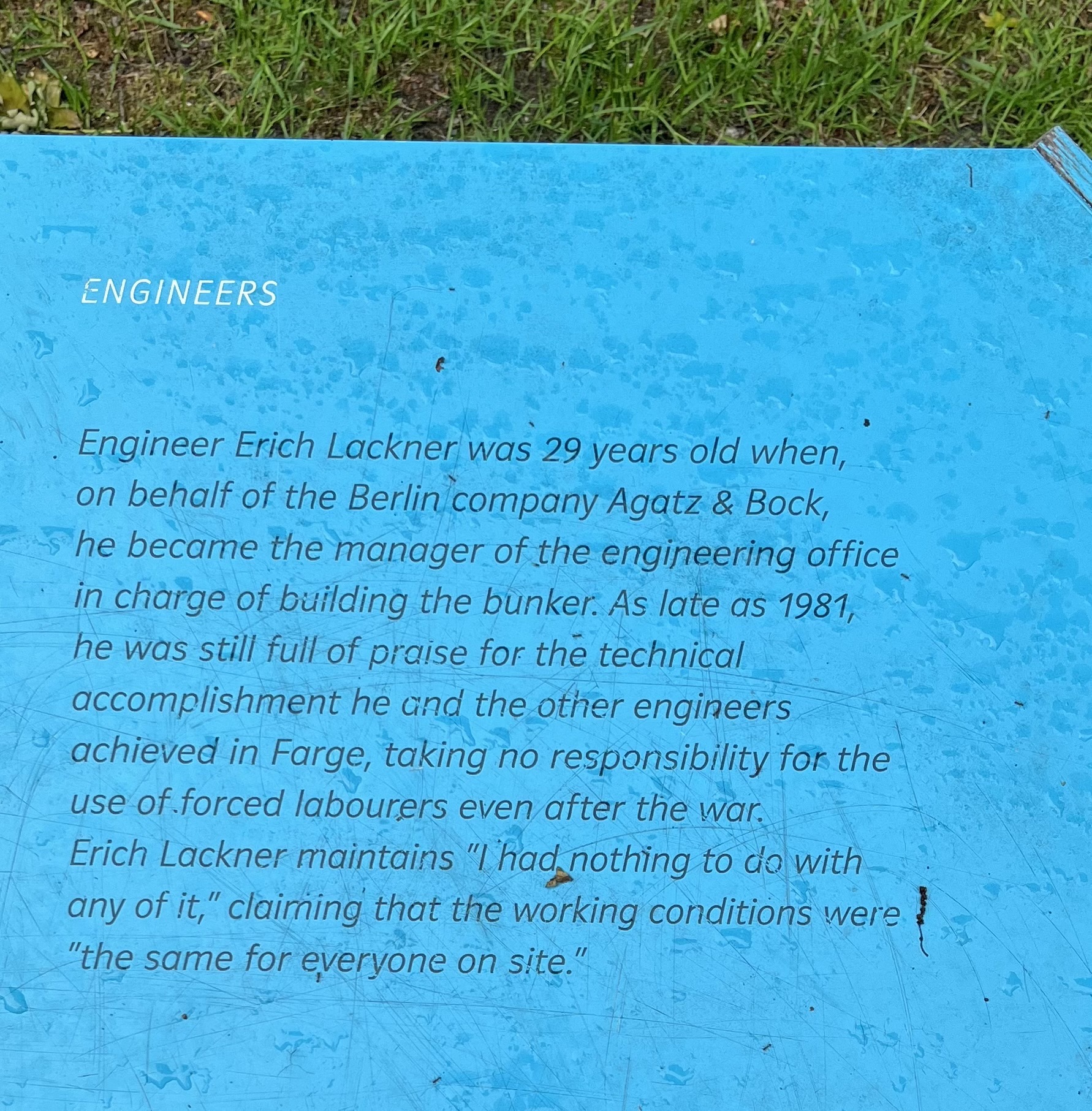

Between May of 1943 and May 1945, almost 10,000 forced labourers – civilians from all over Europe, Soviet POWs, Italian military trainees, concentration camp prisoners, and inmates of a so-calked “corrective labour camp” run by the Bremen gestapo – were forced to perform hard physical labour under inhuman conditions. More than 1600 died during construction of the bunker.

Signs prominently displayed around the bunker ensure that no one who,visits this site can blithely normalize a horrific past.

The unfinished western section of the bunker roof was destroyed in a British Royal Air Force attack in late March 1945; construction stopped shortly afterwards, and no submarine was ever built in the “Valentin” Bunker. After the war, the bunker was used by the Allies as a target for bomb tests. The bunker was so strongly constructed that demolition plans failed.

Little evidence remains today of the fuel depot projects of the 1930s, the huge submarine bunker construction site or the forced labour camps, but in the early 1980s, former prisoner organisations, local initiatives and associations, and committed individuals called for the establishment of a memorial at the “Valentin” Bunker.

Only after the German army agreed to leave the bunker (which they’d been using as a storage facility) in late 2010 did it become possible to realise the memorial project, which was funded equally by federal and state governments. In 2011, the Bremen State Agency for Civic Education began redesigning the grounds into a Memorial,which officially opened in November 2015.

Inside the dimly lit cavernous space, a film is projected onto,one of the huge cement walls. The footage used was commissioned by the Nazis, ostensibly as propaganda. It is chilling to watch it unfold on the wall of a place that was built through so much human suffering.

There is a tour here specifically designed for children aged 8 and up, encouraging them to find the answers to questions ranging from “Who planned this project?” And “Why is the bunker located on the river?” to “Who took these photos?” And “What is forced labour?” History has been maintained here as a teaching tool for future generations.

It was an intense day.

We talked, laughed, visited, had a wonderful lunch at the Bremerhaven Fish Market, and enjoyed each other’s company.

And we cried.

I really admire the way the Germans have accepted and used their past to educate themselves and visitors so that such a thing won’t happen again. I’d never heard of this site but will remember it. Thanks so much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s really interesting to visit various countries’ immigration/emigration centres and see how the stories are presented. We’ve done immigration Pier 21 in Canada and emigration in the small centre in Cobh Ireland and the huge one in Dublin. Bremerhaven was the first that looked at both emigration and the challenges of immigration at the other end.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was reacting to the visit you made to the museum made out of the huge concrete facility made to manufacture submarines — and staffed by prisoners. The emigration/immigration museum was fascinating and very well done, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL…. Yes, THAT was (in the word’s of Monty Python) “something completely different”.

Quite creepy for an “engineering marvel”

LikeLike

So informative and historic. I never knew that museum existed–seems to be so well “preserved” to show the past. I have been to Pier 21 and now know how very important it was to Canadians, I learned when there how important it was to the Jews. Thank you so very much for continuing to share.

LikeLiked by 1 person