“Scenes of Durban”, a panoramic drive to explore Durban’s mix of Indian, Zulu and post-colonial influences.

Our young guide, Dominic Naidoo, a 9th generation Indian South African (that becomes relevant as we continue) was exceptional. Not only did he give us a tour, but in one afternoon he managed to impart an education about South Africa’s complicated history of colonialism and racism.

We travelled by motor coach along downtown streets busy with typical Sunday afternoon shopping and strolling. A busload of white tourists garnered attention; people smiled, waved, and posed as we passed. That’s something we’re used to kids doing, but here the adults were equally enthusiastic.

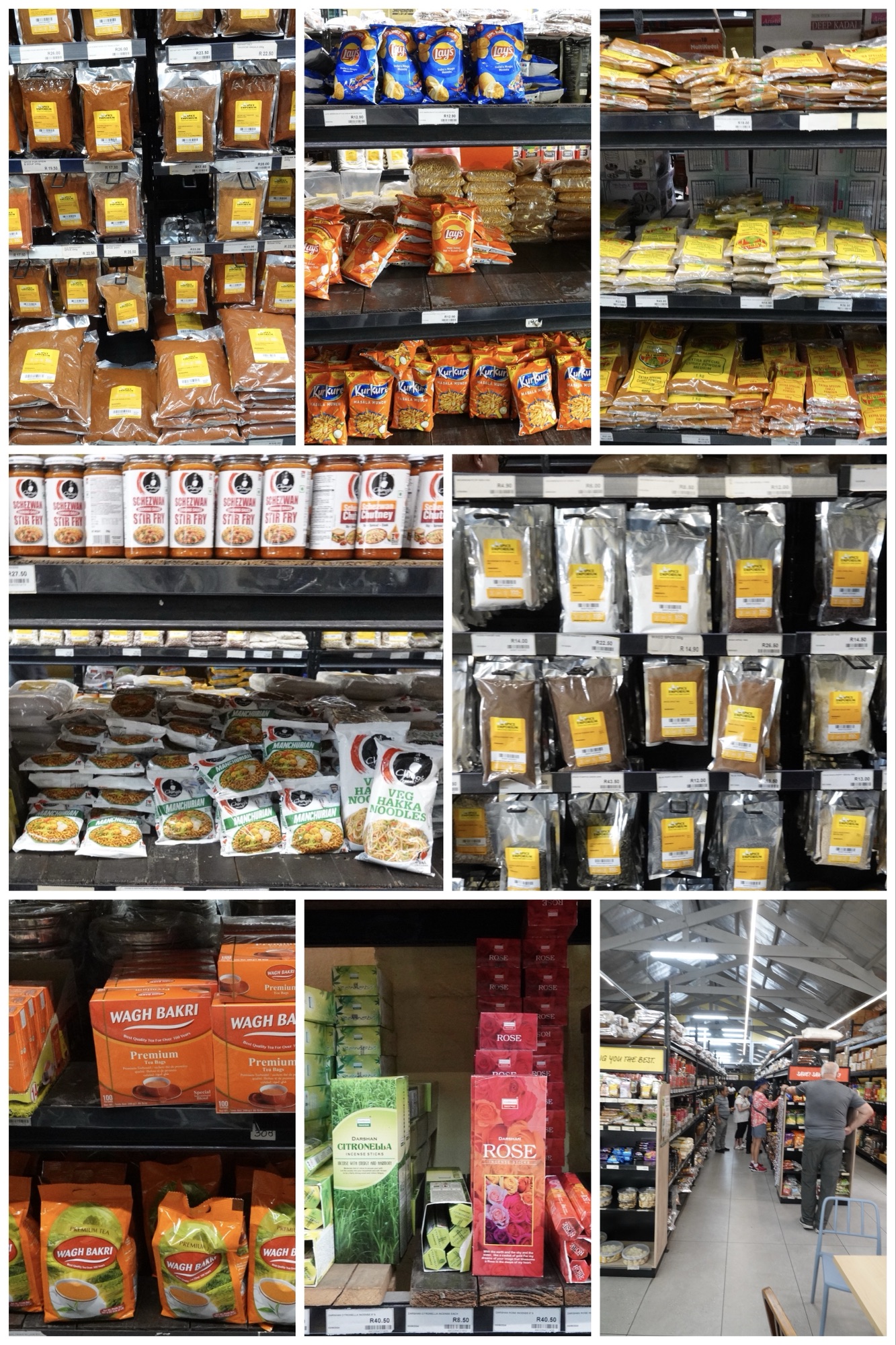

Our first stop was at The Spice Emporium, an Indian spice company store established by the Haribhai family in the early 1900s. Their retail and wholesale business has now been operating for more than 100 years.

As soon as we entered the shop, the delicious smells of masala spices made our mouths water. We had to take tons of photos, since both our sons are spice aficionados.

All that spice… and yet what I bought was incense (for my daughter-in-law) and some jalebi (for me).

Back on the bus, Dominic started to tell us about race history in South Africa. When the Dutch settled there in the 18th century, they built their infrastrucure on the backs of slaves. When slavery was outlawed by the British in 1833/34, the Dutch (Afrikaaners) moved to a system of indentured labour, primarily with Indian immigrants. After 10 years (2 terms of indenture), the labourers’ debt was considered to be paid and they were given 2 acres of land to homestead; South Africa desperately needed people.

We passed the Juma Mosque, completed in 1930, which is the second largest in South Africa. Its gilt-domed minarets protrude above a bustling commercial area of shops, but the marbled worship hall is reserved for peaceful worship. Between 7 and 10% of the enslaved, exiled, and indentured persons brought to South Africa by the Dutch East India Company were Muslim.

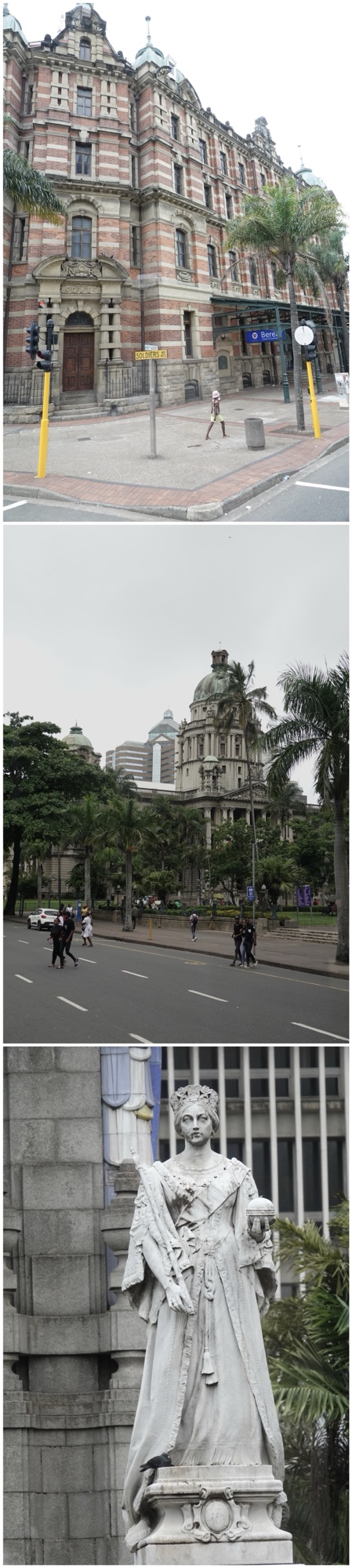

We also got glimpses of the red and white National Railway ticket office (we could not see the train station well enough to photograph), the city hall (which is virtually identical to that in Belfast, having been designed by the same architect), and a statue of the young Empress Victoria.

Much to Dominic’s surprise, we skipped the opportunity to enter the Victoria Market. We’d been cautioned not to wander the market on our own, so the bulk of passengers were too leery to visit it. Dominic mentioned that the market is always on his tours, but he deferred to “us”. I wish I’d protested – folks too wary could have stayed on the bus.

Instead, Dominic continued his history lesson.

After centuries of white rule, and all other races disenfranchised , in 1948 the white minority needed to even further consolidate their power by making apartheid the actual law of the land. The Population Registration Act of 1950 required people to register as black, Indian, white, or coloured – the latter being an official South African designation for mixed-race. Then the Group Areas Development Act in 1955 separated races into completely segregated neighbourhoods. In many cases, that meant moving people out of their homes and off the land that they were given after completing their indentured service. Dominic’s grandparents were of the generation removed from their homes and moved into much smaller houses in a homogeneous (all-Indian) “township”.

During Apartheid, Indians were “luckier” than blacks, who were limited to a grade 5 education, menial labour, and limited infrastructure (water/electricity/roads). Indians were allowed to complete some high school, to prepare them to be support staff and “better servants”. Whites, of course, could attend university.

All non-whites had to carry identity cards, plus work cards that proved they were authorized to be out of their own area.

Dominic characterized the Afrikaaners as incredibly smart, since they knew that by isolating the races they could best keep them from getting to know each other and potentially becoming allies. He lamented the waste of intelligence.

Most shocking about all of this were the numbers involved: in 1950, white Afrikaaners represented less than 20 percent of the entire population, yet controlled 92% of all privately owned land. Black native South Africans constituted about 70%, Indians 2%, and “coloured” 8%. On top of that, the 1950 Population Regulation Act saw the Indian minority as “having no historical right to the country”, despite having been there since as early as the 1830s (brought in by the British).

Given the country’s history, it is a huge credit to Nelson Mandela and F.W. De Klerk that the dismantling of apartheid was accomplished with relatively little violence.

South Africa’s democracy is still very new, only 30 years, and much remains to be done. In 2024, South Africa is 81.4% black, 8.2% coloured, 7.3% white, 2.7% Indian, and 0.4% “other”, and yet that 7.3% white population still owns 72% of the country’s privately owned land, including agricultural holdings. The land that the government has bought back since 1994 for infrastructure projects has often been at inflated prices, and it is only very recently that land expropriation for public works has been discussed.

Dominic explained why identification by race is still considered important. Despite everything, it is still a much needed way for blacks to advance to better education and jobs, since laws require that if two candidates have equal qualification, the black candidate must be hired.

It was a lot of very disturbing information, related in a very engaging way.

Thankfully, it was time for our longest stop of the excursion.

We had an hour to independently wander Durban Botanic Gardens, the oldest surviving botanical garden on the African continent. It was developed in 1849 as a station for the trial of agricultural crops, but today focuses on core areas of biodiversity, education, heritage, research, horticultural excellence, and green innovation. The gardens were full of families enjoying Sunday afternoon gatherings, photo sessions, and picnics; they were also full of birds and free-roaming vervets.

After leaving the park we had a photo stop at the Moses Mabhida Stadium, built to host some of the 2010 FIFA World Cup Soccer games, when the stands (which hold about 66000) were filled with the deafening sound of vuvuzelas.

Our last scheduled photo stop was to admire the vistas at the Currie Road panorama viewpoint.

En route back to the ship we drove along the Golden Mile beachfront and past the tree-lined Victoria Embankment, also known as the Esplanade—one of the city’s oldest and most famous streets. This – along with the other affluent areas through which we passed – used to be exclusively white. Now anyone who can afford to live here can, regardless of race.

We returned to the ship just in time for our 6:00 p.m. sail away, reminding us again of why we like taking Viking’s excursions: the ship waits for us.

The evening’s entertainment was a classical concert featuring Liza (our resident pianist), Neva and Petar (our classical string duo, on cello and violin, respectively), and our Assistant Cruise Director Patricia, also on violin. They were terrific, and the audience reaction was a testament to a desire for more main stage classical performances.