Cairns, as we’re learning is the case for much of Australia, has a complicated history.

We’re very used to stories of 16th and 17th century Spanish and Portuguese explorers arriving in foreign lands, “discovering” them as if they’d just been formed, and ignoring, undervaluing, or even trying to exterminate the indigenous peoples and cultures, superimposing their European religion and mores.

We’re less used to thinking about that happening in the 19th century during the height of the British Empire.

That’s something we’ve been learning much more about on this cruise.

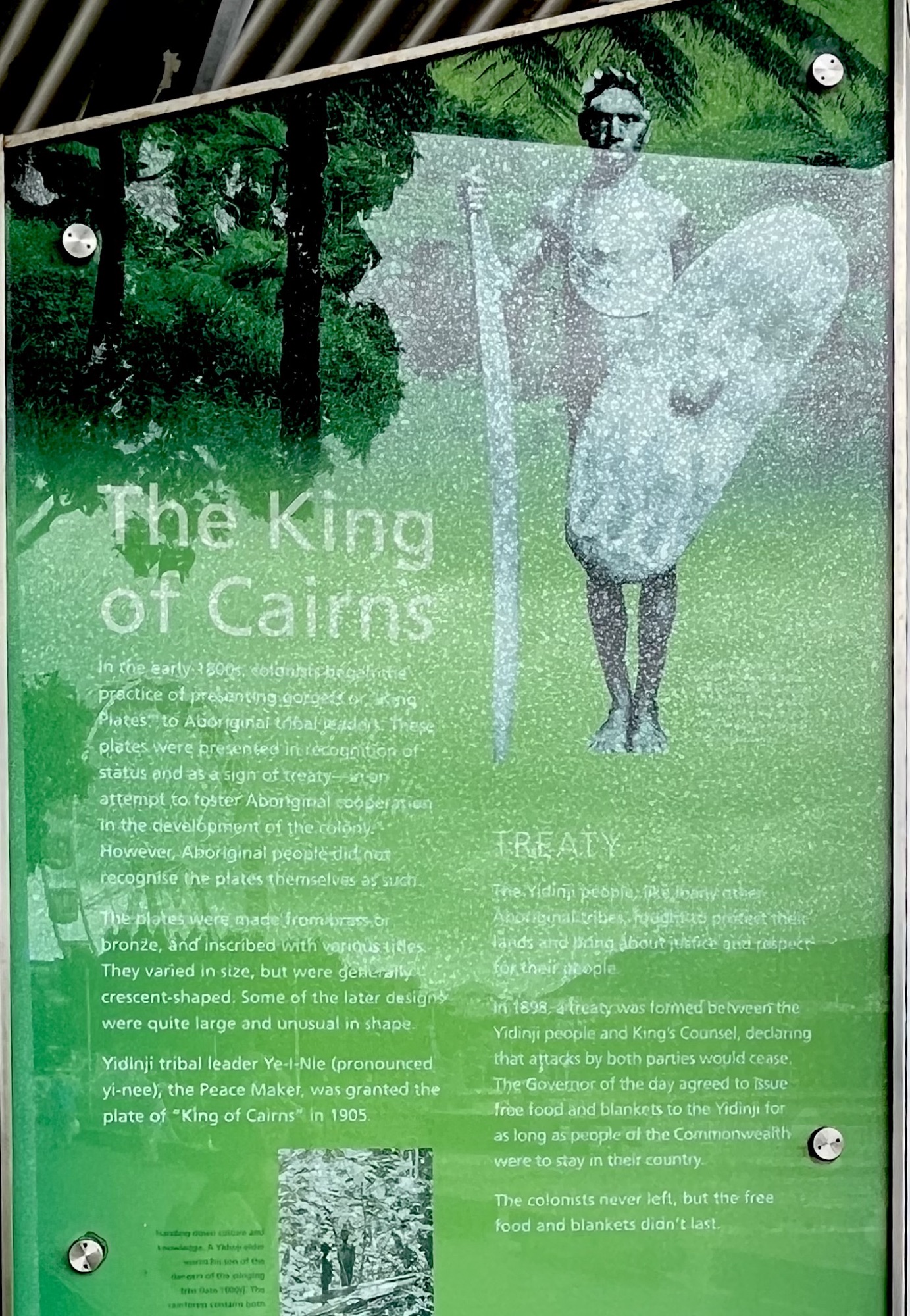

When the British arrived here, the area was already settled by the Gimuy Walubara Yidinj people. That clan claimed native land rights, which were very different from the British concept of individual land ownership (something we are having reinforced over and over during onboard lectures). Nonetheless, the British claimed, subdivided, and sold parcels of land to colonists.

However the Aboriginal people did not recognise the plates themselves as such.”

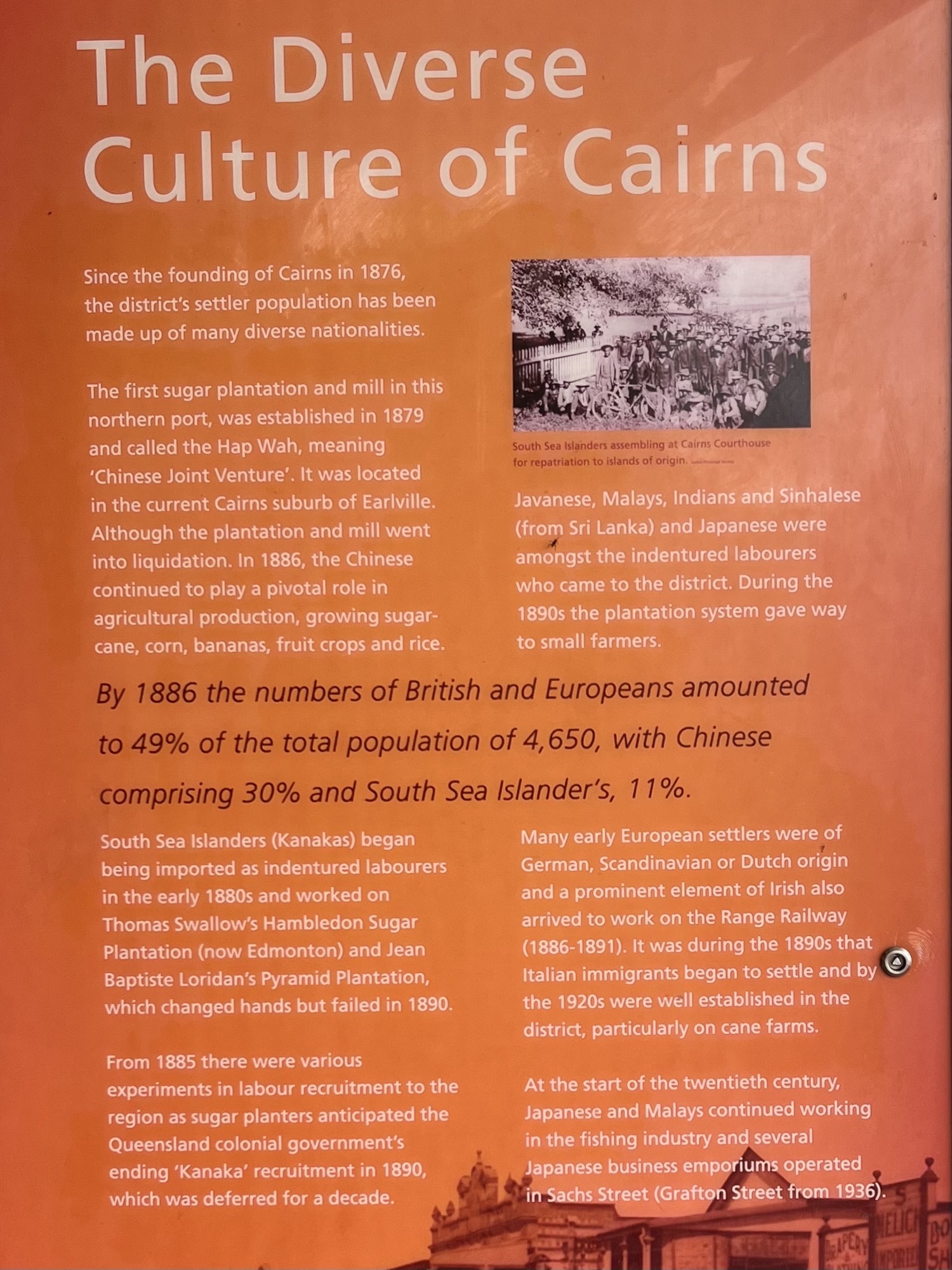

On another common theme, the area prospered from the settlement of Chinese immigrants. By 1886 the Chinese population accounted for 60% of all farmers and 90% of gardeners here. Those workers and their families were thanked (sarcasm alert) for their hard work by the implementation in 1901 of the “White Australia” policy, an immigration restriction act, a “set of racial policies that aimed to forbid people of non-European ethnic origins – especially Asians (primarily Chinese) and Pacific Islanders – from immigrating to Australia in order to create a “white/British” ideal focused on but not exclusively Anglo-Celtic peoples.”(White Australia Policy).

That policy was not repealed until 1975.

The policy also affected the aboriginal people; according to Wikipedia, by 1912, all Aboriginal people of mixed descent were removed from Aboriginal reserves around Australia, with the goal of assimilation into the white community. The principle of assimilation also led to the removal of Aboriginal children from their families and cultures. This sounds eerily familiar to Canada’s residential school programs. The British Empire in many ways did the same things that the Spanish and Portuguese did, only using different strategies.

Learning these kinds of things certainly adds perspective to the statues and plaques we see.

This was another 2-day port stop, although we didn’t arrive until after lunch on day one. Unfortunately, the included excursion to the Aquarium was fully booked, and since neither Ted nor I were interested in the $1300CAD per person helicopter rides over the Great Barrier Reef, we were left to our own devices.

And….it’s not just raining here today…

When the rain finally died down, just as we were being tugged into Cairns, this poor soggy female lesser frigatebird came to greet us.

We ventured out, intent on strolling Cairns’ beautiful waterfront esplanade. It certainly didn’t disappoint. The wide boardwalk – which stretches for 2.5 km/1.5miles – is lined with marinas, restaurants, benches, viewing platforms, and family friendly parks.

We were very impressed by the huge “lagoon”, complete with lifeguard on duty, and the large number of water play areas, as well as picnic areas with barbecues and tables.

There are also art installations, and interpretive signs explaining their significance. It’s one of the most truly useable waterfront city parks we’ve seen.

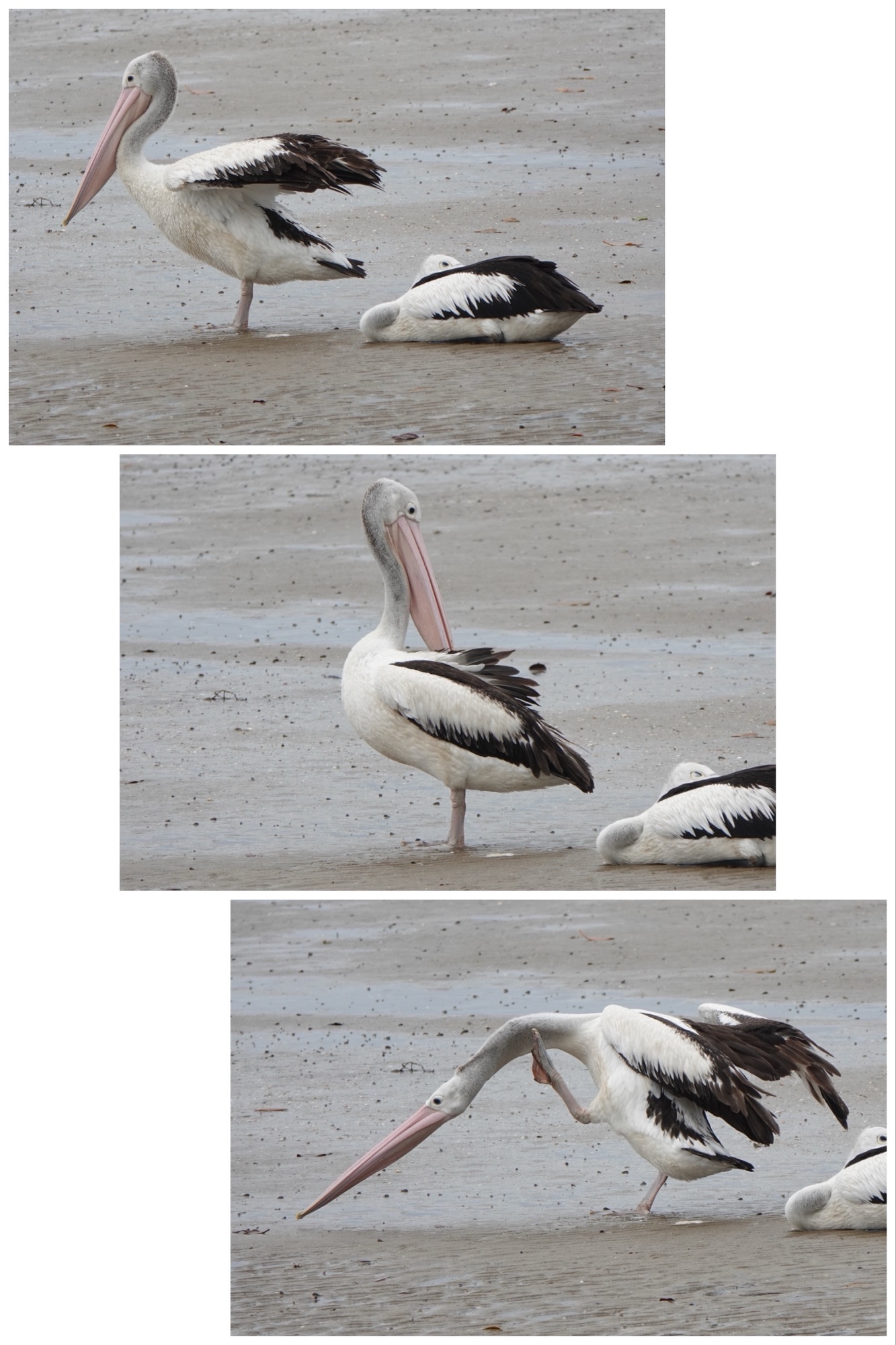

The tide was way out in the early afternoon, turning Trinity Inlet into mud flats that attracted lots of birds, and revealed lots of crabs.

Bottom: mud crabs (seems obvious!)

The Cairns cenotaph is located on the esplanade, where walkers and bicyclists pass it every day. When it was built in 1925 it had a working clock on 4 sides, but now the clock faces are permanently painted to read 4:28 p.m., which is the time at which the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli commenced on the morning of 25 April 1915.

When we’d walked as far along the esplanade as we wanted, we turned around and headed back toward the ship, but walking along Abbott Street. That’s where we noticed the impressive Bishop’s House, and beside it Saint Monica’s Cathedral, girls’ residential high school, and college (in order from top to bottom in the photo below).

The cathedral (the second image) was not particularly attractive from the outside, but I can never walk past an open church door without going inside – and we were both glad of that when we saw the cathedral’s stained glass windows.

We’ve seen “creation windows” before, but nothing like these. The 24 windows are modern, artistically gorgeous, and also very moving.

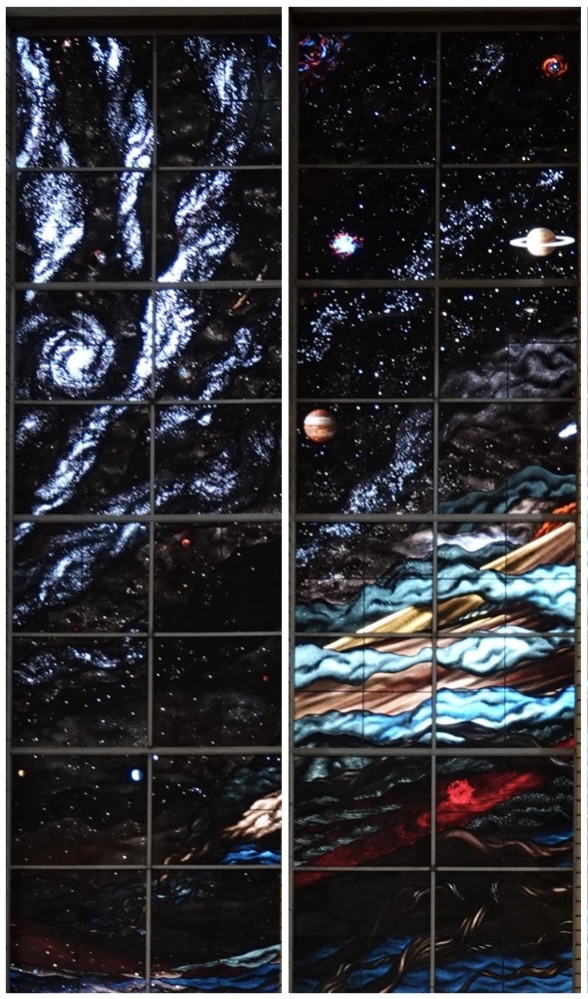

“The first 6 windows were deliberately designed and painted to be dark. They centre on images from deep space.” There is no disconnect here between the concepts of the Big Bang theory and that of “let there be light”. I found the images absolutely unique in a Roman Catholic setting.

The first 12 windows depict the theme of Genesis Chapter 1, “the orderly unfolding of Creation, representing a world as yet uninhabitable to human beings: deep space, the ocean, hot laval landscapes, and a choking sulphurous atmosphere that cannot sustain air breathing creatures.”

Window 1 “incorporates twisting shapes to suggest twining rope, or umbilical cords, or strands of protein from which DNA and life itself will form”. (I’m not making this up – anything in italics and quotation marks is taken verbatim from the brochure handed out at the cathedral.)

Windows 2, 3, and 4 are scientifically accurate images including the Eagle Nebula as revealed by the Hubble Space Telescope, the Horsehead Nebula, the Milky Way, and the Southern Cross constellation.

The next windows show the planets of our solar system. “The bright newly-born stars of the first windows become pink and blue dust and gas clouds, remnants of exploded supernova stars. The heavens themselves participate in this great cyclone of birth and death.”

At the bottom of Window 8, the strands that started in Window 1 begin to take definite form, “coalescing in a point of light that is the creation of life.” Marine life, corals, and sponges are depicted. In Window 9, a volcano explodes, “its red rivers of fire flow across the window and consolidate into land”. One of the things we found fascinating about these windows is that they feature recognizable Australian features. In this case, it is the Undara Lava Tubes, Mount Tyson, and Mount Bartle Frere. Window 10 includes the Chillagoe lime bluffs. Window 11 has Thornton’s Peak, Mount Pyke, and Lighthouse Rock. Window 12 has Australia’s peninsular mountain ranges.

“The ocean begins at the bottom of Window 6 and unfurls across the windows until it achieves its horizon line at the tip of Cape York in Window 12.”

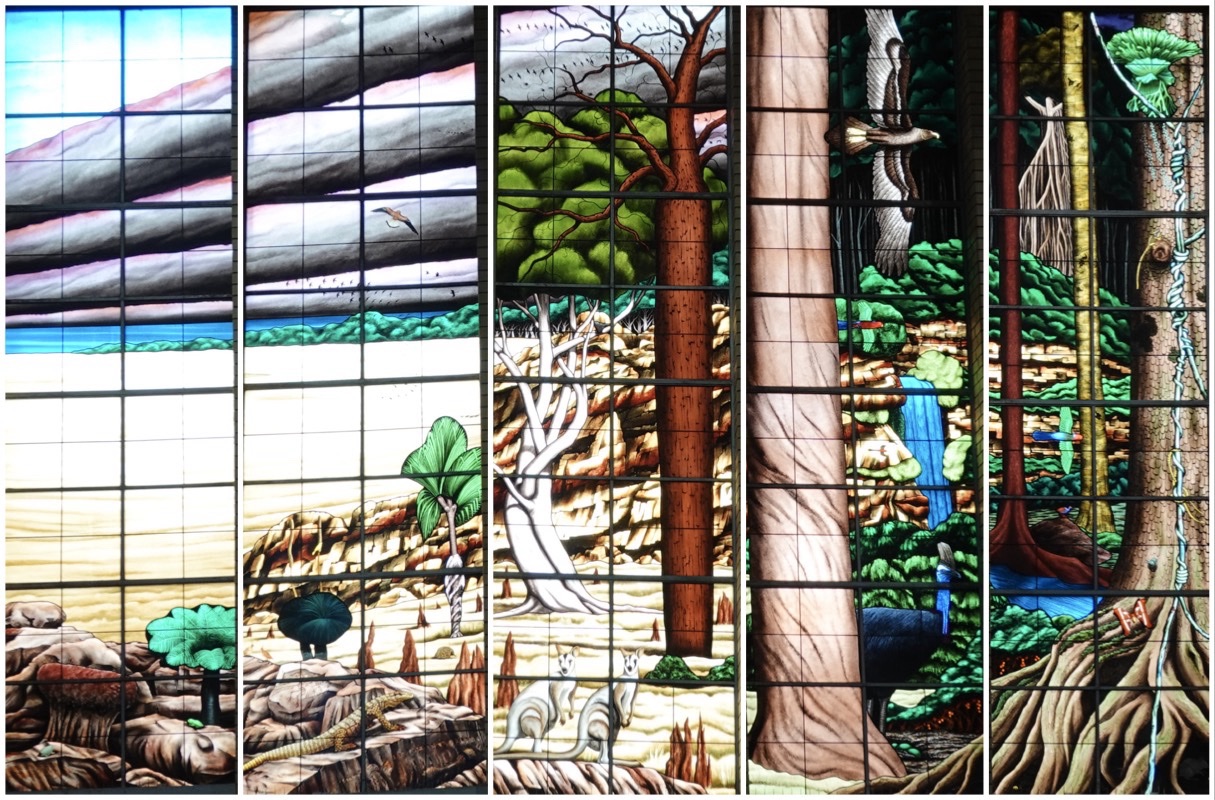

Windows 13 to 20 begin with another trio of themes: landscape, flora, and fauna.

Window 13 shows Australia’s Normanton grassland, and the first fauna is a fossilized stromatalite.

Window 14 includes anthills and the beginning of the Newcastle Range. the fossils from Window 13 now progress to cycads, eucalypts, giant tree ferns and mosses. Birds appear, as well as a monotreme echidna and marsupial wallabies.

By windows 15 and 16 there are waterfalls, by number 17 more birds and mammals (we could identify a parrot, a possum, koala, kookaburra, and platypus – plus a staghorn fern!)

Window 18 brings humans into the picture: a mother who “is the central image representing birth, caring, and love” , “a pregnant woman and another with a child, who represent both future and community”, and “a man representing knowledge, education, and custom, who pauses to point at the prism of light across in Window 2.”

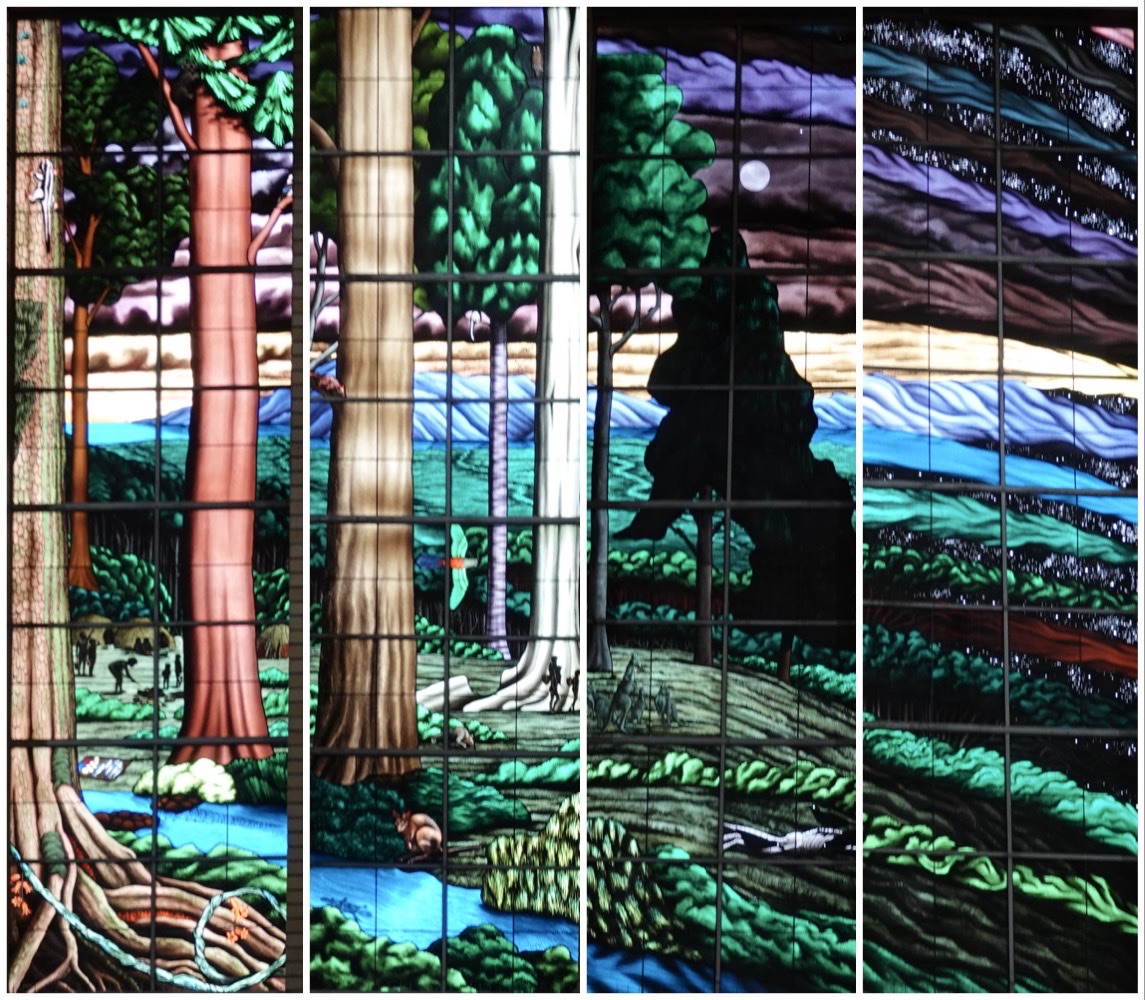

Window 19 and 20 represent an idyllic paradise and a darkness creating paradise lost.

In Window 21, “the sky bursts into life as the physical world melts away …all things are returning to God.

Windows 22 – 24 depict “the Day of the Lord … the sky will vanish, the elements will catch fire and fall apart, the earth and all that it contains will be burnt up” to create a “new heaven and new earth”. Central to these 3 windows is a 100mm two-hundred-faceted crystal sphere which, when struck by the morning light, casts a beam of rainbow spectra across the inside of the cathedral.

It really made a big impression on us.

It was a hot and very humid humid day. Before going back to our ship we stopped at a waterfront brewery for a cold beer.

I was amused by the signs on the LONG trek to their washrooms.

After a quick but delicious dinner in the World Café, we headed to the theatre to meet our new quartet of Viking Vocalists performing the ABBA Songbook. They were great!

Those stained glass windows are amazing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those windows are amazing! Your habit of looking into church doors really paid off. For your readers too. Thank you for sharing them in such detail.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We were in Cairnes last week and had rain as well. It wiped out two of our three excursions but we did make it to snorkeling the Great Barrier Reef on day three. We went to the aquarium on one of those rainy days. Many of your pictures were places we went including Hemingway Brewery. They had such good pizza that we actually went back two more times during our stay. We stayed very close and it was just easy. We are back home in Phoenix now but much of your trip recently are the same places we just were before, during and after our latest Holland cruise. By the way, our Westerdam staff had the most organized shore excursion organization and disembarking we’ve ever had on Holland. I remember your experiences were less than you thought they should be before. I enjoy reading about your travels.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad to hear that about the Westerdam, since HAL will probably be in our future at some point.

LikeLike

W

LikeLike

I

LikeLike

Amazing that you found that cathedral by accident! It seems like there should have been a tour… Thanks for the complete photo tour of the windows. — They go on the list with Sainte Chapelle’s in Paris and La Sagrada Familia’s!

LikeLiked by 1 person