I was intrigued by the title of Black Cake, by Charmaine Wilkerson, because Trinidadian black cake was served at son #1’s wedding to his gorgeous Trinidadian-heritage wife. Each guest took home a small slice of the dense liquor-soaked cake to put under their pillow, much like English folk do with fruitcake (a 16th century tradition for the “groom’s cake”). My daughter-in-law has just begun the genealogical journey into how her originally East Indian family ended up in Trinidad generations ago; this book is also a journey into the back-story of an island family, albeit one with secrets of the kind our daughter might not want to uncover in her searches!

Having so enjoyed Black Cake, the author’s endorsement of Under the Tamarind Tree, by Nigar Alam, convinced me to read it next. The story moves between 1964 – 17 years after the Partition of the British Raj that arbitrarily defined the borders of India and Pakistan – and 2019, when events resulting peripherally from that separation continue to haunt future generations. As was the case in Black Cake, secrets thought long buried resurface and must be confronted, and things are not always ways what they seem. I’m continuing to enjoy novels that combine historical events with personal stories, especially when they also give some insight into cultures that we may never get to experience firsthand.

I had hoped to read Immigrant, Montana by Amitava Kumar, but it wasn’t available through Libby, our online library. Luckily, I’d been given a hard copy of one of his other non-fiction works, My Beloved Life. The novel reads like two memoirs: one a man of my parents’ vintage, and the other his daughter, of mine. I was fascinated but the story of two generations growing up in India. Spanning from 1935 almost to present day, the novel delves into how the culture in which we are surrounded shapes so much of what we become… and how individual lives can in turn shape cultures. I have to admit that the differences in how women in India, and Indian women in North America, were treated – as compared to what my own experience as a woman of European heritage has been – was at times shocking, and made me even more grateful for the life I’ve had growing up, however imperfect it may have been.

Midnight, by Amy MCulloch, takes place on a luxurious expedition ship headed to Antarctica. If the description of a rough Drake Passage crossing weren’t enough reason to re-convince me that this kind of trip is not for me, the murders on board – far from land, laws, and available rescue – sealed the deal. Nonetheless, it was fun reading a well-researched novel describing what it’s like to take part in one of those amazing Antarctic expedition cruises.

After a couple of heavier themes, I returned to Jacqueline Winspear’s Maisie Dobbs series with An Incomplete Revenge, thanks to patiently staying on the waiting list. This is the 5th book in the series, numbers 3 and 4 inexplicably not being in our library’s e-book collection. In this outing, Maisie’s detective agency in the city is suffering from the same economic struggles as the rest of post-WWI England, so she gratefully accepts what seems like a simple case in picturesque rural Kent during hop-picking season. As we all know from watching Midsomer Murders, though, small towns and rural settings often hide thinly disguised xenophobia and deadly secrets.

Bone and Bread, by Saleema Nawaz, took me back to Indian themes, but this time set largely in Montreal’s Jewish community of Mile End. The story centres around two sisters, daughters of an Indian father and Irish mother, raised with a confusing mix of values, rituals, and beliefs. They are orphaned as teenagers as the unintended consequence of what was to have been an act of kindness, and that hangs over their relationship, further complicated by one sister’s struggle with anorexia and the other’s inability to help. When the sick sibling dies, the surviving sister goes on a journey that involves reliving memories not only of their often odd childhood, but also of how their lives were affected by separatist politics in Quebec.

Death in a Darkening Mist is book 2 of Iona Whishaw’s Lane Winslow mystery series, in which Lane – a former British intelligence agent hoping in vain to find a simple, peaceful life in rural British Columbia – once again gets drawn into solving a murder. Her facility for the Russian language proves useful this time, since the murdered man is a Doukhobor. (Doukhobors are a sect of Russian dissenters, many of whom now live in western Canada. They are known for a radical pacifism which brought them notoriety during the 20th century. Today, their descendants in Canada number approximately 30,000, with one third still active in their culture. ) Of course, there’s always a second – or third – plotline, and this time it’s embezzlement at the town’s bank, and the ongoing progression of Lane’s relationship with Inspector Darling.

This is turning into a binge-worthy series, so I immediately borrowed Book 3, An Old Cold Grave, in which this time the murder has nothing to do with espionage. In fact, the murder appears to be decades years old – a child’s body discovered under the Hughes sisters’ root cellar. I quite enjoyed the move away from Lane’s war-time career toward what her role in King’s Cove might look like as she settles into her life there, as well as continuing to “watch” Lane and Inspector Darling trying hard to resist their growing feelings for each other as the indefatigable Constable Ames tries to push their relationship along.

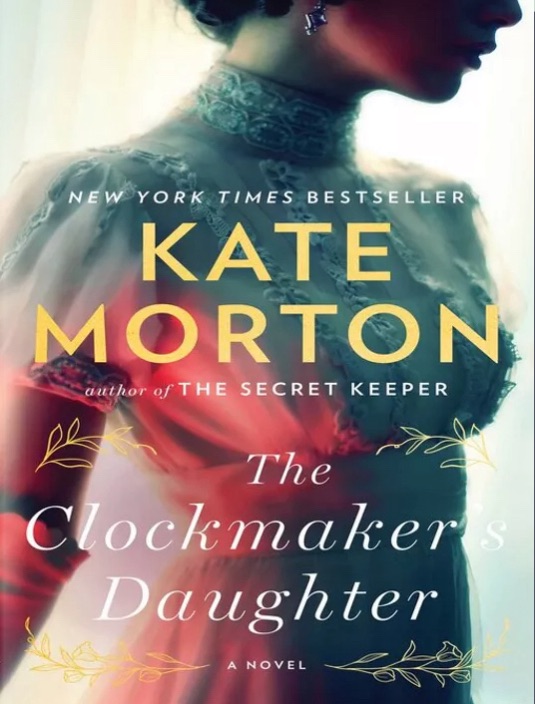

A friend recommended Kate Morton’s books, and although my library records showed me borrowing Homecoming back in April, and returning it in 3 days (which, to be fair, sounds like the amount of time it takes me to read a book), I can’t remember actually reading it, so I borrowed it again. Naturally, after the first chapter it became familiar, so I returned it in exchange for another of Kate Morton’s books: The Clockmaker’s Daughter. Spanning from the 1850s to the present day, the novel is set at the English estate of Birchwood, to which a young archivist named Elodie is drawn after finding an old sketch of a house she thought only existed in her childhood bedtime stories. The history of the house and how it connects to Elodie is revealed through the narrative of a young woman (the clockmaker’s daughter of the novel’s title) who died there in 1862. It’s a ghost story of the very best kind.

I read both Educated, by Tara Westover (loved it) and Hillbilly Elegy, by JD Vance (meh) way back in 2020, Episode 110 . I’ve read a few memoirs since then, as well as Jessica Bruder’s non-fiction treatise Nomadland, about some of the inventive ways in which homeless people in the US survive Episode 452 . Those books were sad and depressing, but also showcased human resilience. The Sound of Gravel by Ruth Warriner, recommended by a friend, shared those elements, taking us into Ruth’s very strange breakaway-sect polygamist Mormon family where she gradually discovers that people don’t always practice what they preach. The often harrowing impact of a life within a religious “colony” are all revealed through a young girl’s eyes.