Like zoos of old, marine “theme parks” like SeaWorld have come under a lot of scrutiny, and endured a lot of justifiable criticism over recent years. There’s no doubt that capturing marine animals and “caging” them for our amusement is a bad idea, but SeaWorld – I believe – has learned valuable lessons, and has gradually turned its focus to rescuing, rehabilitating, and conserving marine wildlife.

It’s still a theme park, and they still offer lots of “interactive” experiences where humans get closer to seals, dolphins, whales, and penguins than those animals might normally prefer, but it is also “one of the world’s foremost zoological organizations and a global leader in animal husbandry, behavioral management, veterinary care and animal welfare.” They rescue and rehabilitate animals (over 40,000 in the past 50 years in all their locations) that are ill, injured, orphaned or abandoned, with the goal of returning them to the wild. Years ago we witnessed their manatee rescue operations in Florida, rehabilitating animals injured by boat propellers.

It would be great – but naive – to think that all their work could be funded by charitable donations; the theme park aspect raises significant funds.

So, on to our day!

The last time we were in a SeaWorld was 1989 in Florida, when our boys were 6 and 8, and I kept thinking today that the park would have been much more fun with kids along – or of Ted or I were the least bit interested in roller coasters and rides. As it was, there was a lot of walking; some very entertaining shows featuring orcas, dolphins, pilot whales, sea lions, and otters; and a couple of very enthusiastic marine biologists that we had pretty much to ourselves on an off-season school day.

At our first stop, the Moray Eels Talk at Explorer’s Reef, Alexander spent half an hour with us telling us all about moray eels, and then turned out also to be our expert for the Octopus Talk. There were plenty of eels visible in their tank, but the young male octopus was so well hidden that even Alexander couldn’t find him.

The two most interesting things I learned from Alexander were (1) that eels have two separate jaws, which aid them in moving food into their long body, and (2) that lamprey eels (those scary open-mouthed jagged-toothed monsters) aren’t actually eels at all. Alexander was right that the faces on “his” eels are almost cute. Not scary at all. Still slimy and snakelike and yucky though. Sorry, Alexander.

It’s interesting that SeaWorld has several levels of staff that interact with the public: “Ambassadors” who give directions and have a cursory knowledge of the wildlife in the park, “Educators” who have been trained by SeaWorld and can specialize in specific animals – although they do not need any formal education beyond high school, and Trainers/Keepers who work directly with the animals and are either Marine Biologists or Zoologists (Alexander was the former), and have degrees ranging from a BSc to a PhD supplemented by things like scuba certification. Then there are all the behind-the-scenes staff like veterinarians, research scientists, animal behaviour specialists and more. It’s easy to see why they need things like theme parks to supplement their funding.

From the eel and octopus learning experiences we headed to our first “presentation” (they no longer call them “shows”) of the day: the Orca Encounter. There was a walk and talk scheduled 30 minutes prior to the aquatic presentation, but no one ever showed up to lead it, so the entire group of people waiting in vain finally just headed to the amphitheater.

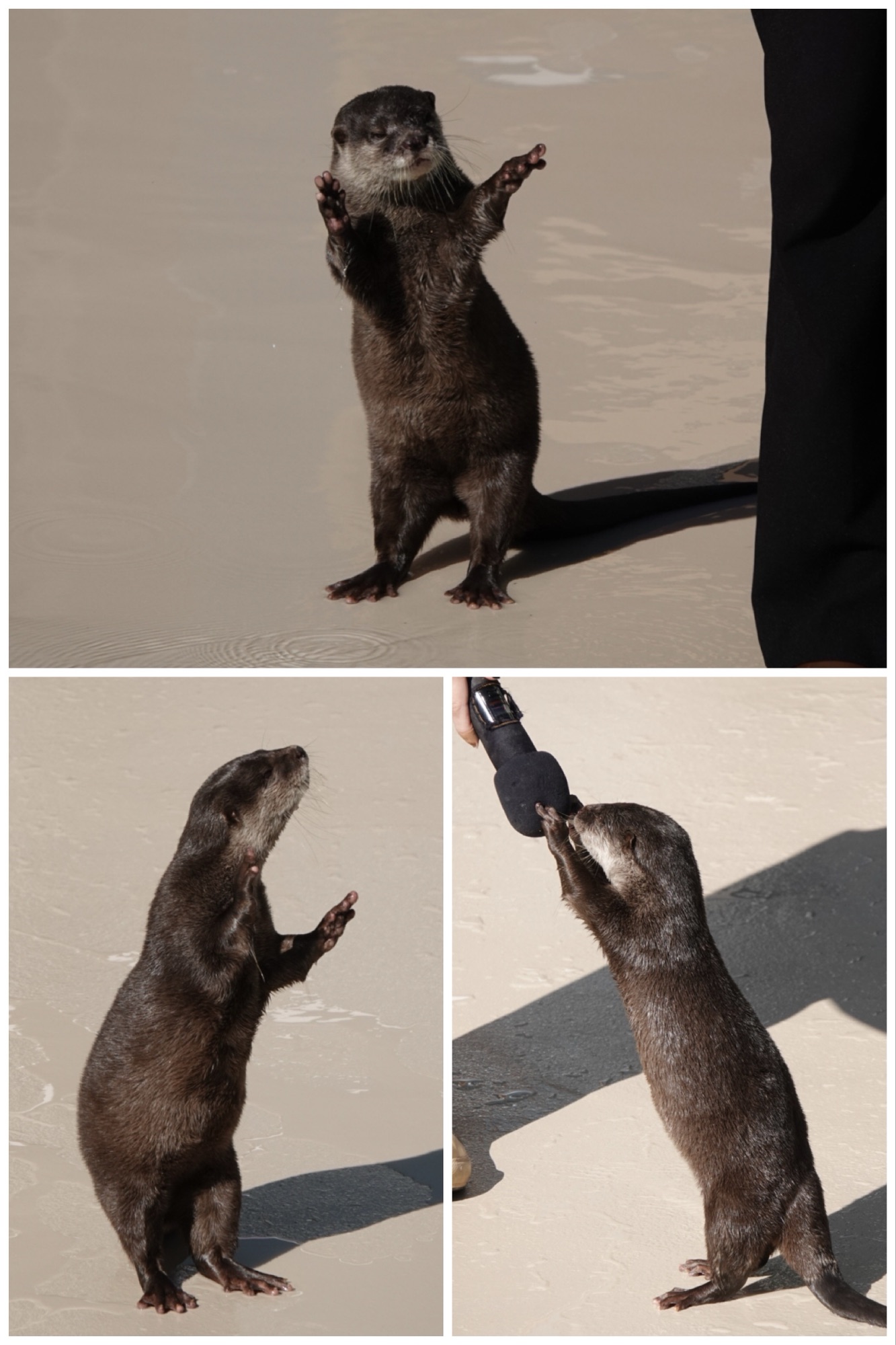

Our next dual experience was the Sea Lion Keepers talk, followed by the Sea Lion & Otter Spotlight. The session with the “keeper”, a marine mammal zoologist this time, gave us some insight into how the humans here interact with the animals. The sea lions are very social animals (at night, they sleep on land in what he described as a “sea lion pile”) and love to mimic, whether that is each other or a human with whom they’ve bonded. That makes them very easy to “train”, since most of what they do is copy their human’s motions in return for extra fish. So a full grown sea lion wiggling their backside to “dance” with their keeper is a bit of a game, as is the echoing vocalization. Sometimes, of course, they simply don’t – and swim off to play. They get the extra fish anyway.

Besides sea lions, there were also a couple of harbour seals, easily identified by their lack of seal “ears” and their spotted fur. In the wild, harbour seals live an average of 25 years. SeaWorld San Diego’s oldest harbour seal is Anna, who is 43 years old and has, as they described it, outlived her eyesight. Her eyes look pink due to opaque cataracts, but she is so familiar with her surroundings, and has such keen senses of smell, hearing, and touch, that her blindness doesn’t seem to cause any problems.

The sea lion pool attracts dozens of snowy egrets, hoping that people feeding fish to the seals will be careless and drop some. We have never seen egrets as bold as these; they didn’t move even when we stood close enough to touch them. SeaWorld staff were quick to tell us that the egrets are not theirs, but simply wild local birds who think they’ve found a good restaurant.

The Seal & Otter Spotlight included a hilarious pre-show featuring Biff, the maintenance man, and his iPod full of music to which he mimed and danced as he “cleaned” the stage. I kept thinking how much our grandsons would have laughed at his antics.

That set the perfect tone for the always amusing sea lions, and Opie the mischievous otter. No one explained to us exactly how you train an otter….

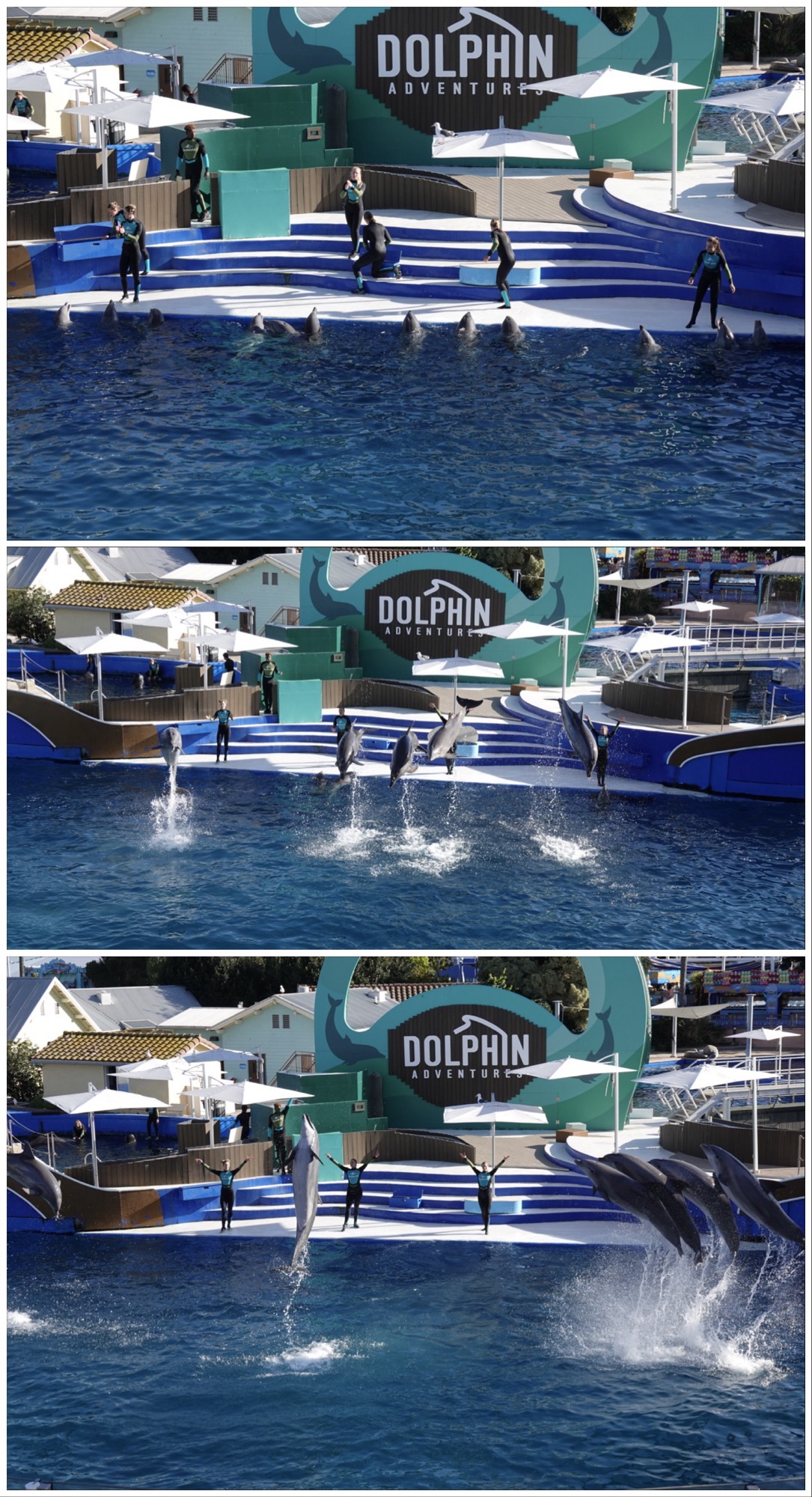

After a short break for a lunch of smokehouse ribs and fries – part of our meal package – it was time for another presentation: the Dolphin Adventure, featuring 12 bottle-nosed dolphins and two pilot whales.

The park closes early during off-season, at 5 p.m., so we just had time for a quick cold drink and a snack before heading to Shark Encounter, an aquarium housing bamboo, hammerhead, nurse, lemon, leopard, and reef sharks, among others, in a 280,000-gallon tank. Similar to Ripley’s Aquarium in Toronto and others we’ve visited, there is the chance to walk through a 57-foot acrylic tube surrounded by swimming sharks, which lets you see their undersides. Photos through the thick acrylic are pointless, so we just enjoyed being “immersed”.

At the entrance to the exhibit is an open tank housing fairly small bamboo sharks who just seem to be sleeping on the bottom. Andrew, the marine biologist on duty, explained that the idea that sharks need to swim constantly in order to breathe is somewhat of a myth. Apparently only a very few of the oldest species – like great whites – need to stay in motion in order for oxygenated water to pass over their gills. Many sharks, like the bamboos, have spiracles: round sphincter-like vestigial gills through which they can “inhale” water. The spiracles are located high on the sides of their bodies, so they can rest on the sandy ocean floor and not ingest sand. Andrew reminded us that eels and rays also have spiracles instead of gills.

Before leaving the park, we said a quick hello to the Magellanic penguins. We’d seen them in their natural habitat on our world cruise, Episode 190 – Penguins and noted that here at SeaWorld – without thousands of squawking, pooping skua around – their habitat was much cleaner!

And that was our day!

Would I do it again? Maybe not. At least not without grandkids in tow.

For us, Balboa Park has much more to offer, especially considering that our single day at SeaWorld, with food package, cost as much as an annual pass that gets us into all 16 of Balboa Park’s museums.