I’ve become fascinated recently, maybe partially due to watching the excellent HBO series The Gilded Age, with what has happened to the incredibly rich and powerful families who made their fortunes in the 1800s – the industrialists, railroad barons, sugar kings, hoteliers, and more.

Sure, Paris Hilton might be in the tabloids, and Anderson Cooper is a Vanderbilt, but how often do we see or hear the names Astor, Rockefeller, Dupont, Morgan, Duke, Carnegie, Roosevelt, Whitney, and Hearst – except as the names of buildings, or on the walls of galleries and concert halls as benefactors?

Today, there was another somewhat familiar name: Putnam. Opened in 1965, in a modern building within Balboa Park, the Timken Museum of Art preserves the Putnam Collection of European old masters, American art, and Russian icons.

I immediately thought of Putnam Books, but was that right? Who were the Putnams and Timkens related to this gallery?

The museum’s information says that Anne and Amy Putnam were sisters who arrived in San Diego with their family in the early 1900s. In the 1930s and 40s, Anne and Amy began to purchase European paintings of distinction, which they anonymously donated to the Fine Arts Society. Doing some quick research of my own, it was easy to find out that the Putnam name goes all the way back to a Puritan colonial family, who early on had the dubious distinction of being Salem witch trial accusers. And yes, their huge family tree includes the founder of Putnam Books, but also military heroes, sugar plantation owners, railroad owners, judges, doctors, sculptors – and the husband of Amelia Earhart!

But not, after all – except perhaps very distantly – the Putnams related to this museum.

Anne and Amy were the daughters of Elbert Putnam, and nieces of Henry Putnam, an industrialist and businessman who invented and patented (among other things) the wire-fastener type bottle cap. They were apparently reclusive spinster sisters who inherited $5 million USD from their cousin Willie Putnam, Henry’s son.

And the Timkens? The fortune that helped endow the San Diego Museum of Art was created by Henry Timken, an immigrant from Germany as a child, who became an inventor and businessman, and the founder of the Timken Roller Bearing Company. Although the Timken family was based in Ohio, they wintered in San Diego.

So much for being sidetracked by the names of this space’s benefactors. There’s an actual museum to explore!

The Timken is quite small – just 6 galleries with about a dozen pieces in each – but that’s part of what makes it so attractive. You don’t have to spend a whole day, or worry about missing something.

On entering the museum, we were greeted by music being played on the grand piano in the central gallery/lobby. Lovely, and it really set the tone for our visit.

The other nice bonus was the presence of a volunteer docent in each of the galleries, allowing for lots of interaction and learning.

We began in the Italian/Spanish gallery, where this 14th century Florentine Madonna and Child with Two Angels, painted in tempera on wood, raised some questions. My first comment to Ted was that the Madonna, angels, and even Jesus all seemed to have goitres. (Since having half my thyroid removed in 2018, I see goitres everywhere.) Naturally, when we got home I had to research thyroid disease in Italy in the 1300s. Imagine my surprise at very quickly finding a 2015 article from The American Journal of Surgery entitled Thyroid swellings in the art of the Italian Renaissance. ScienceDirect. Ted gave me a pat on the back for correctly spotting the symptom in the art.

Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress painted in 1530 by Italian artist Bartolomeo Veneto, a contemporary of Titian, impressed me with the gorgeous detail in the touchably realistic fabrics. Interestingly, the artist really didn’t seem to be able to paint realistic hair though – it looked almost like brown magic marker.

By contrast, in this 1650 painting Return of the Prodigal Son, by Italian artist Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) the hair is so lifelike you want to run your fingers through it. The museum’s docents pretty strenuously discourage any attempts.

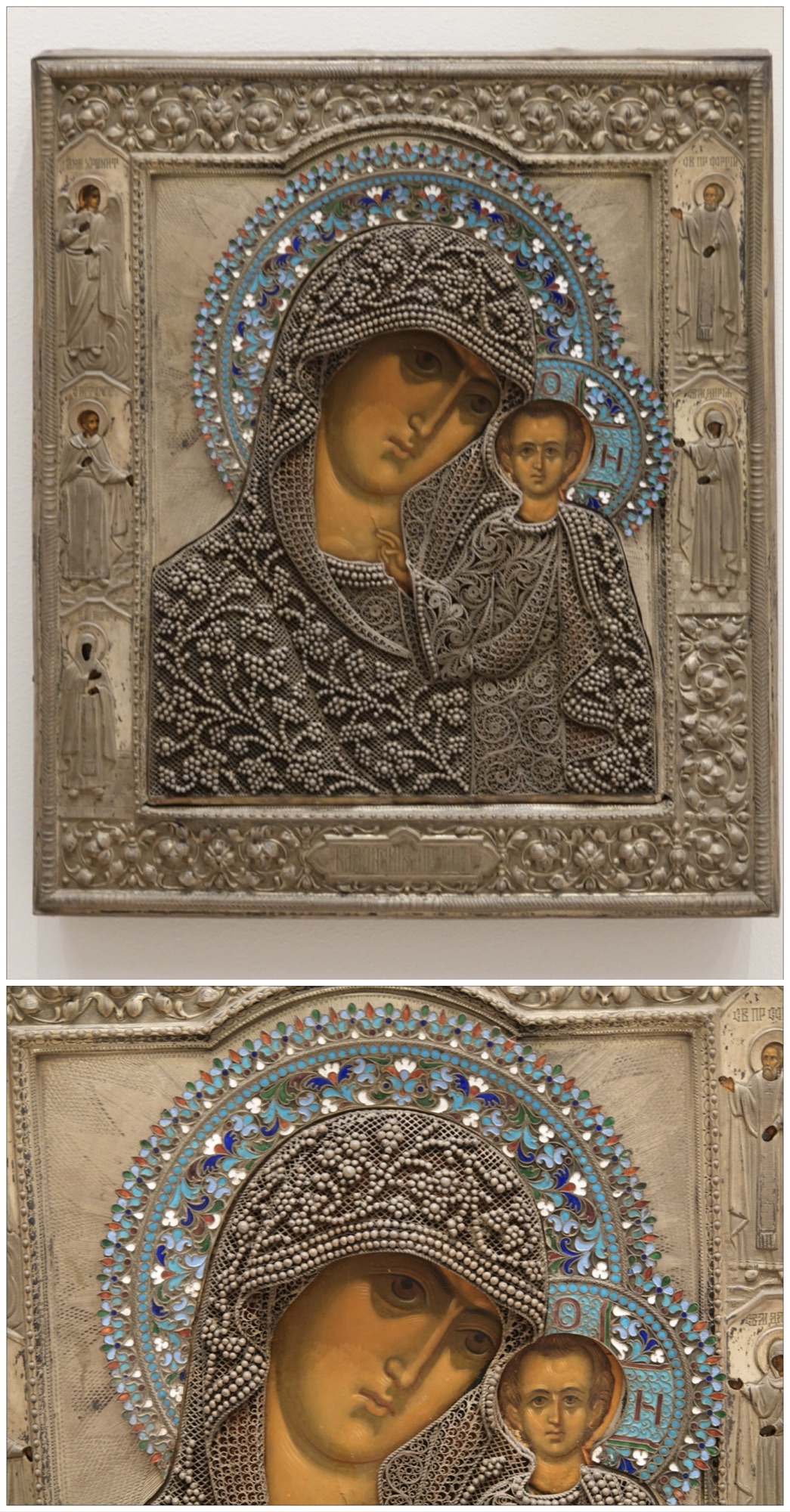

We’ve seen many, many Russian icons in museums and galleries in North America and in Europe, but we’ve never seen a calendar icon before. How fascinating to think that people would so carefully keep track of every single “saint day” in order to offer up the correct daily prayer.

When we were in Orthodox churches in Croatia, we saw several “adorned” icons, where the actual painting is covered with precious metal, often leaving only a portion of the face revealed. The adornment supposedly reflected the icon owner’s piety, but realistically was a gauge of their social status, aesthetic taste, and financial resources.

In the Dutch/Flemish Gallery many of the pictures exhibited the dark colours and “flat” feel I’ve come to associate with early Dutch art. This mid 15th century painting by Flemish artist Petrus Christus was interesting mostly because of its rather unique theme: the Death of the Virgin. With thousands of famous paintings depicting the crucifixion of Christ, this is one of only a few focused on the end of Mary’s life.

The special exhibitions gallery contains one of the museum’s most famous and beloved paintings, François Boucher’s 1758 painting Lovers In A Park, currently being restored and conserved.

Art restoration is a process usually completed behind closed doors, but here at the Timken it is being carried out in full view, 3 days per week, over 4-6 months. In fact, for a few hours on Thursdays and Fridays museum visitors can interact with the conservator as she works.

At one end of the gallery is a cordoned-off workspace where the painting, out of its usual frame, is mounted.

Zooming in, Ted’s camera could capture the worn edges, the cracked seam in the canvas where Boucher stitched two pieces of canvas together to create his large work surface, and the white “bloom” mark where the paint was damaged and will be restored.

The gallery included a display showing just a few vials of pigment from the Forbes Pigment Collection, comprised of over 2500 pigments at Harvard University’s Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. The description reads “The Forbes Pigment Collection was created at the turn of the 20th century and stands as the world’s largest collection of historical pigments. They serve as an important reference for conservators, scientists, and and technical art historians. Balboa Art Conservation Center (BACC) is one of only a handful of institutions that were gifted a subset of this extraordinary pigment collection, maintaining a tangible connection to the the beginning of the professional art conservation movement in the United States.”

We were also able to learn about the many steps – and high-tech tools – used in art conservation. Each of the 4 quarters of this full-size mockup of the painting, placed in its actual frame (it has to be stored somewhere, after all), show a step in the assessment process that occurs before conservation can begin.

(UPPER RIGHT) UV light is used to look at the surface of a painting, revealing the presence of varnishes as well as areas of retouching and restoration. (LOWER LEFT)X-ray can reveal the canvas weave, paint losses, old repairs, or changes made to the painted composition.

(LOWER RIGHT) Infrared reflectography, which is invisible to the human eye, can show underdrawings and changes made by the artist.

It really was an amazing insight into the process, but we still had more to see!

In the French gallery, I was reminded of one of the (many) reasons we return over and over to art galleries and churches. Far from being repetitive, there always seems to be a new snippet of history to learn – or re-learn. This 1802 Portrait of Cooper Penrose by Jacques-Louis David wasn’t particularly interesting to me … except for the bottom right corner! Under his signature, David dated the portrait formally in Latin “faciebat Parisiis anno Xme republicae Gallicae” – made in Paris the tenth year of the French republic, using a calendar it turns out the artist himself helped to inaugurate. Until seeing this painting, I’d completely forgotten learning about the calendar created after the French Revolution to “replace” the Gregorian calendar. It didn’t last, but remains in places like this portrait.

Also in the French gallery were these 1729 portraits by Nicolas de Largillière of a husband and wife, interesting both for their stunning artistry and for what they say about the people in the paintings. Barthélemy Pupil “married up”, and as a result was awarded a series of increasingly prestigious legal appointments in Lyon. Once he could afford to have his portrait done by an important artist, he made sure it included his satin judicial robes, long powdered wig, and beautifully leather-bound legal text. On the other hand, his wife’s portrait shows off her sumptuous clothing and furs, a silver fan, and sheet music reflecting how cultured she is. The docent pointed out to us that they’re the perfect stereotype of 18th century French society: a “man of laws” and a “creature of culture”.

That only left the American/British gallery, where the painting that drew me was Salomé, painted in 1890 by American painter Ella Ferris Pell, who rose to prominence as an artist in the decades immediately following the American Civil War. This was the first major oil painting by a woman to join the Timken’s permanent collection.

And that was it – quite a lot, really, for such a small museum. The much larger art museums of Balboa Park still beckon!

<

div dir=”ltr”>I sent his blog to jenniferdanton. I was dazzled th

LikeLike

Thanks for the tour. I love small museums. I like leaving with a feeling of having really seen it all. I especially like ones where the sensibility of one collector or couple is in evidence — kind of like studying the hosts’ bookshelves during a party to learn something about them, too. The Kreeger Museum in Washington DC is a favorite. www.kreegermuseum.org

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad I’m not the only one who checks out people’s bookcases!

LikeLike

Wow! You get so much out of visiting a museum. I can’t do that without a guide. You have seen more in less than a week than people who live in San Diego all their lives. Al

LikeLiked by 1 person

We always see more in tourist mode than we do in our own cities, don’t we? It’s why I love having visitors – so I can be the tour guide and see things with fresh eyes. Looking forward to doing that with the two of you in July!!

LikeLike